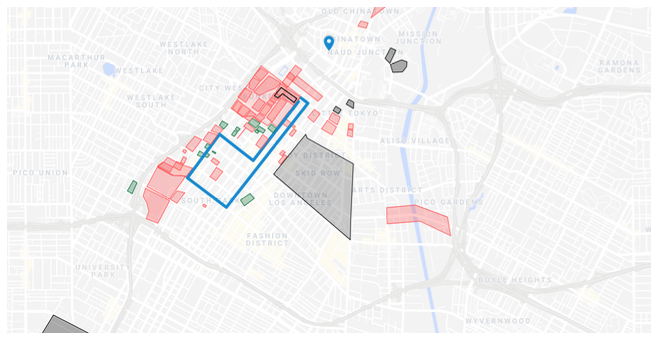

CommentsDEVELOPERS’ DREAM COME TRUE-Look at the map above. Here we can see the decades-long project to attract rich people and maximize property values.

Huge swaths of Downtown LA — almost the entire western half — have been redeveloped for the rich with public support, contributing to rising rents and the gentrification of the entire region.

(RED = developments that have benefited from public land or public money; GREEN = zoning changes; GRAY = carceral institutions, within which I’ve included Skid Row due to its intense policing; and BLUE = the Downtown Streetcar. (full interactive map with details for each development here)

As the news breaks that homelessness in Los Angeles has jumped 12%, to nearly 60,000 people, perhaps the most frustrating number is 55,000 — that’s how many people were newly forced into homelessness last year. Even as we spend what we are told are large amounts of money on addressing the crisis, the housing market is evicting low-income tenants faster than we can house them. While most children could probably understand that ever-increasing rents would lead to ever-increasing homelessness, our local leaders are “stunned.”

Although LA certainly isn’t the only city with a housing crisis, and we should recognize that this is the result of a deeper system in which land is used for profit and represents 60% of all global assets, that doesn’t mean we should assume our local politicians are powerless, and therefore excused. On the contrary, they’ve worked hard to bring about precisely this result, having undertaken a decades-long project to attract rich people and maximize property values (and thus rents).

In effect, they’ve worked overtime to make this city as hostile as possible to working-class tenants.

The Grand Avenue Project downtown — located just across the 101 freeway from the Hillside Villa Apartments, where hundreds of people facing eviction are asking the city to purchase their building for just $9 million to keep it permanently affordable — provides a striking illustration of the downtown our leaders want to create, and the type of development they will spend our money on.

In 2016 LA’s City Council approved $198 million in public financing for The Grand, crowning an extensive public-private partnership, begun in the early 2000s, to develop the parcels around the famous Walt Disney Concert Hall — itself located on public land and the beneficiary of $110 million of county money. This last phase has been led by the charter-school-loving billionaire Eli Broad, designed by the renowned architect Frank Gehry, and is being developed by the massive NYC-based Related Companies. Upon completion, there’ll be luxury apartments, a boutique hotel run by Equinox (the fancy gym company), and a shopping center filled with “lucrative brands and ‘celebrity-chef-driven concepts.’”

Former Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa calls this “egalitarian.”

Worse yet, the Grand Avenue Project sits on Bunker Hill, where decades ago the city’s powerful Community Redevelopment Agency used eminent domain to buy, and then literally clear, 140 acres of land, displacing 11,000 people. Beginning in the late 1960s, and continuing into the present day, the neighborhood has been steadily sold off to large corporate developers for high-rise mega-projects, mostly offices and hotels, in an effort to kick start the “revitalization” of the entire downtown area.

A rendering of The Grand, which sits on public land and will receive up to $198 million in public money.

Mike Davis, one of the most critical observers of LA in the last several decades, recently said of this intensely privatized and policed enclave: “Of course, your museum patron or condo resident feels at home, but if you’re a Salvadorian skateboarder, man, you’re probably headed to Juvenile Hall.”

But it’s not just Bunker Hill — huge swaths of downtown have been remade in a similar manner.

What gets built with public support has little to do with the needs of the masses of people who live in LA, and everything to do with the needs of rich residents and tourists who want luxury attractions, and of global investors and local landowners (including homeowners) who want to profit from high property values.

By mapping out these developments — those which have received vast sums of city or county money, public land sold at below-market rates, or preferable zoning changes — we can see just how powerful and extensive the “real estate state” is in Los Angeles.

Crucially, furthermore, creating such an affluent downtown that anchors the transformation of the entire region.

It has spurred the ongoing gentrification and displacement of nearby neighborhoods that are now more desirable due to their proximity to an opulent core, banishing “working-class communities of color to the far margins of urban life”; it’s contributed to the tens of thousands of people sleeping on the street, as the elites succeed in making the city as expensive as possible; and it’s necessitated the harsh policing of unhoused residents and the overwhelmingly Black population of Skid Row, in addition to “one of the largest systems of human caging that the world has ever known” — the yuppies and property values must be protected at all costs.

The housing crisis is no accident, nor is it natural. It’s been steadily engineered by each successive generation of LA’s ruling class, all of whom have dedicated themselves to building a city for rich consumers and profit-seeking landowners and investors.

Below I’ll highlight just some of the major projects downtown. For a more complete list, see the interactive map here.

Here’s the map again. (A wider version.) You can see the two major poles of state-driven redevelopment in the northern corner (Bunker Hill), and in the southwest corner (South Park), with more luxury projects scattered throughout the rest of downtown.

The Convention Center, Staples Center, LA Live, and so many hotels (“South Park”)

As the Bunker Hill project was redeveloping downtown’s northwest edge, the city enthusiastically embraced one of the core tenets of neoliberal urbanism in order to provide a foothold for revitalization in the southwest corner. South Park, as the area came to be known, would be remade as a center for tourism and entertainment.

The first major step was to expand the Convention Center, which required the city in the 1980s to borrow $500 million through the bond market to build new facilities on about 30 acres of land where the 10 and 110 freeways intersect. This necessitated the uprooting of the people who already lived there, of course.

Huge amounts of public money went into making South Park the neon-corporate hellscape it is today. (photo from the LA Department of Convention & Tourism Development)

By 1999, one block to the north, the Staples Center was completed, displacing 250 more people.This arena is widely considered to be the single most important project in downtown’s history, laying the groundwork for the boom of the 2000s. The city provided $70 million in public funding to the firm AEG, owned by Philip Anschutz. Anschutz was dubbed “the man who owns LA,” by the New Yorker Magazine, is a major Republican donor, and has a net worth of over $10 billion — clearly someone who deserves our tax dollars.

According to the President of AEG, Staples is “probably the most profitable building in the world.”

So our politicians showered AEG with even more money. In 2005, the city provided another $270 million of our money to close the “funding gap” for LA Live, a massive entertainment complex bordering Staples Center on the north. LA Live includes a big outdoor plaza, some fancy hotels and restaurants, 224 luxury condos, and a concert venue. It is, like Staples, also considered to have been “crucial to downtown’s resurgence.”

Then in 2012 came $67 million for a Courtyard Marriott, and in 2017 $42 million for the Cambria Hotel, both one block to the north of LA Live. Then in 2018 came $103 million for a hotel across the street from Staples to the east, followed quickly in 2019 by another $98 million for a hotel within LA Live.

How does this happen? The city’s Department of Convention and Tourism Development preaches the need for more hotel rooms, the city’s Chief Legislative Analyst takes the word of consultant reports — “paid for by developer funds” — that claim the need for public money for these projects, and City Council finishes the job by approving these massive corporate giveaways, almost always by a unanimous vote.

Fortunately, the benefits trickle down for everyone — just ask the folks at the Freehand Hotel, where workers suffer from a rabid anti-union campaign by management, on top of “ICE threats, homophobia, and literal shit.” In all seriousness, though, even with the most benevolent corporate employers, the negative impacts of these projects on land values and rents are not made up for by the low-wage service-sector jobs they provide: LA has a minimum wage of $15/hour, whereas you’d have to earn $47/hour to afford median rent in the county.

We can do better than an economy based on attracting rich people to our city.

Bunker Hill — a quick revisit

I went into some detail about Bunker Hill above, but it’s hard to overstate its importance. According to UCLA professors Gilda Haas and Allan Heskin, the neighborhood was slated to be used for 10,000 units of public housing until the plans were destroyed by “powerful real estate and business interests.” They controlled the Community Redevelopment Agency (CRA) and were able to direct tons of local property taxes and federal dollars to “pave the way for the new corporate downtown.” This local agency, now dissolved by state-level action, bought and literally flattened the entire area, selling off massive parcels at below-market rates for high-rise office towers, hotels, and luxury apartments to well-connected developers. These developments, and the land they sit on, are now worth tens of millions of dollars each, at least.

Here’s Bunker Hill in the 1970s. You can see how the city literally cleared and flattened almost 140 acres of land in the heart of downtown LA. When this photo was taken, only a few projects had been built — two high-rise office towers and a few luxury apartment developments.

The area around Bunker Hill has also been used strategically by the city to spread gentrification eastward.

For example, in the early 1990s the CRA and Metro issued $44 million in bonds to help Ira Yellin, a close ally of Mayor Tom Bradley, renovate the Grand Central Market and nearby buildings. First, local government agencies agreed to move into some of the office space to help him pay back the city. Then, instead of foreclosing on him, Yellin was repeatedly allowed to default on his debt, essentially being gifted millions of dollars, multiple times. A CRA executive explained that the space was “a very, very important component of our downtown redevelopment.”

Today, Grand Central market is experiencing a “renaissance,” but only for some — in 2015, longtime commercial tenants filed a lawsuit against what they claim has been a blatant plot to oust non-white businesses in favor of ones that cater to different (whiter) people.

Similar efforts have been made to Bunker Hill’s east in Little Tokyo, like when the CRA assembled and sold the land for the New Otani Hotel (now the Double Tree) to a massive Japanese corporation for just $1 million in the late 1970s. In 2017, the property sold for $115 million.

Public Goods for Private Gain

Admittedly, a good portion of the land that’s been redeveloped is still technically public and meant to serve the broader community. But many of these projects contribute substantially to raising property values and therefore happen to also be great deals for those who own land nearby, revealing deeper — or at least dual — motives.

Let’s start with the LA Central Library — how could the redevelopment of a library possibly be motivated by real estate interests? Well, it’s located just one block from Bunker Hill, in the heart of the financial district, and the renovation occurred precisely when the city was making big moves to remake this area in the 1980s. Plus it was explicitly tied to nearby high-rise office development. To pay for the renovation the city sold air rights to a developer of two adjacent parcels. Maguire Thomas Partners paid the city millions of dollars in exchange for the ability to build much higher towers, vastly increasing the value of their properties. One of these, the US Bank Tower, is now on sale by its Singapore-based owner for $700 million.

Then there’s the downtown streetcar (the blue line on the map at the top). In 2018, City Council approved $600 million for its construction and maintenance for the next 30 years. The line will only cover a small portion of DTLA, connecting Bunker Hill and South Park with the corridor on Broadway that is presently a prime focus by gentrifying developers and their politicians. Even the boosters at the LA Times Editorial Board see what’s going on and oppose it. They argue that it’s supported primarily by “real estate investors” whose land would be made more valuable by the streetcar, and the public shouldn’t pay for “a project that’s designed to serve commercial interests.”

$437 million of public money was spent on the new LAPD headquarters. That’s on top of a budget of $1.5 billion per year.

In 2009 the city spent $437 million on sleek new headquarters, adjacent to City Hall, for the most murderous police force in the nation (LAPD). A few years later, the city released a new master plan for the area, located between Bunker Hill and Little Tokyo, that offers a “transformative vision” for a “Civic Innovation District” — you can’t make this stuff up!

And in 2016 the city decided it will spend $482 million to rehabilitate and build a park underneath the Sixth Street Viaduct, running over the LA River connecting the Arts District and Boyle Heights. With the Arts District booming and Boyle Heights being increasingly eyed by real estate investors, surely it’s just a coincidence that the latter, a heavily Latinx neighborhood long neglected by the city, will now be the beneficiary of a beautiful park connecting it to downtown’s eastern flank.

Finally, of course, there’s the 2028 Olympics. Untold amounts of public energy will be put towards mobilizing nearly $7 billion of private money to hand over our city to rich tourists for two weeks. Imagine if the bureaucrats working to make the Olympics happen were focused on ending homelessness instead.

Meanwhile, we haven’t built a single unit of public housing since 1955. [

Criminalization and Incarceration

Lastly, you can’t (or shouldn’t) talk about creating a city for the rich like LA while ignoring those who are most oppressed by the very same system. All this luxury redevelopment has occurred during the rise of mass incarceration, and it’s helpful to think of the neoliberal turn not as being about a weaker state, but as a more pro-market one. Sometimes that looks like deregulating markets and letting capitalist forces and actors do as they wish, and sometimes, as we see above, it looks like transferring massive amounts of public money and land to profit-seeking developers.

For poor people, and especially for Black people, it looks like intense police harassment and being locked in cages. Los Angeles imprisons 618 people per 100,000 residents, which is 3x the rate of Venezuela and 10x the rate of Sweden. In 2016 14,000 unhoused people were arrested, nearly 40 per day. LAPD’s budget is $1.5 billion per year.

In 2006 the city embarked on a plan to provide 50 additional cops, and other security enhancements, to Skid Row, whose population is overwhelmingly Black. This was called the Safer Cities Initiative (SCI). For years the official policy, literally, was to “contain” Skid Row, but now that investment is picking up all over downtown, the ruling elites want to disperse it. Police harassment can help do just that. During the first year of the program, the city made “9,000 arrests (in Skid Row) and issued about 12,000 citations (primarily for crosswalk violations),” and Alex Vitale estimates the city spent $150–200 million on SCI over the first four years.

There are also about 20,000 people locked in cages in downtown or right outside its borders. There’s a jail run by the LAPD, a prison run by the federal government, and two facilities run by the Sheriff’s Department. It cost at least $500 million to construct all these buildings, and that’s not counting the costs of staffing/running them, or the $2 billion that will soon be spent to renovate one of them.

Those who pose a threat to profit-making and yuppie’s enjoyment must be warehoused. This is not a bug in the system, but a feature.

A massive success

Ultimately, the elites have been wildly successful: LA is the most desired location for global real estate investors in North America, and Mayor Garcetti can cheer that we’ve “been named the most economically vibrant city in the world.” On the flip side, the county’s Black population has declined by 150,00 since 1990, 650,000 children are hungry, and LA is one of the most unaffordable places on earth. These are the contradictions of a booming city under 21st Century capitalism; ones that our politicians have enthusiastically embraced at every step of the way.

(Jacob Woocher is a grad student in Urban Planning and Law at UCLA. He is active in the LA Tenants Union (LATU) and can be reach @jacobwooch through Twitter. This piece was originally published in KnockLA.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.