HEALTH POLITICS--Huntington Memorial Hospital in Pasadena, Calif., has been in the news twice in the past two weeks. But the stories weren’t about one of its doctors discovering a cure or inventing a new life-saving procedure. They were about 11 tragic deaths that occurred at the hospital and about the hospital’s costly and illegal union-busting campaign that forced Huntington into signing a settlement agreement with the California Nurses Association.

This is what happens when a hospital puts profits over people—its patients as well as its employees.

The 625-bed facility made headlines when it reluctantly admitted that 11 Huntington patients had died between January 2013 and August 2015 after being infected by dangerous bacteria from medical scopes. Another five patients were infected but are still alive. The hospital acknowledged the deaths only after the Pasadena Public Health Department (PPHD) was about to release a report about the outbreak of multi-drug-resistant (MDR) pseudomonas aeruginosa linked to procedures (called endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography) performed with scopes made by the Olympus Corporation.

The city agency’s investigation, which began last August with an unannounced site visit and continued with cooperation from hospital staff, blamed both the design of the scope and the hospital for lapses in infection control. For example, according to the report, the hospital used canned compressed air from Office Depot to dry the scopes—which is not recommended by the manufacturer or by nationally recognized cleaning guidelines. The PPHD report triggered stories in the Los Angeles Times headlined “11 deaths at Huntington Hospital among patients infected by dirty scopes, city report says” and “Pasadena hospital broke the law by not reporting outbreak, health officials say.”

Initially, Huntington only notified patients who had been treated with the scope between January and August 2015 about the possibility of infections. The PPHD, after it began its investigation, insisted that Huntington notify all patients who had been treated with the scopes since January 2013. The PPHD had to ask Huntington twice to notify those earlier patients before the hospital complied.

The duodenoscope is, according to the Times, “a long snake-like tube with a tiny camera on the tip that is inserted into a patient’s throat and upper gastrointestinal tract. It is used to treat cancer, gallstones and other problems in the bile or pancreatic ducts.” The PPHD report concluded: “This broad bacterial contamination supports the hypothesis” that the hospital’s disinfection and maintenance “were insufficient to prevent the spread of infection.”

“We take responsibility for the deficiencies outlined in the [Pasadena Public Health Department] report and have taken steps to ensure rigorous compliance going forward,” wrote Derek Clark, the hospital’s director of public relations, in an email response.

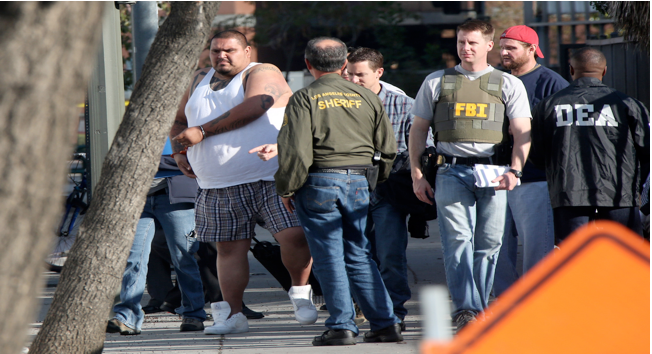

The same week that the story about the deaths broke, Huntington also made news when it reluctantly agreed to a settlement with the California Nurses Association (CNA). The hospital agreed to rescind the firing of registered nurses Allysha Shin (whose last name was Almada before she was married last October) and Vicki Lin and restore their full back pay. Both were illegally fired as part of Huntington’s vicious and expensive anti-union campaign last year.

The results of last year’s union election were overturned. The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) will determine a new election date. Huntington also agreed to abide by labor laws that protect the RNs’ right to organize and agreed to post its commitments throughout the hospital and email the notice to all nurses.

It would hardly be news that a hospital has agreed to obey the law, except that Huntington so egregiously broke the law last year that they had to put it in writing before CNA would approve the settlement agreement.

During last year’s organizing campaign, the union caught Huntington engaging in dozens of illegal acts of intimidation designed to prevent the nurses from gaining a stronger voice in their workplace. CNA brought these unfair labor violations to the federal National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), which ruled against the hospital. Hospital officials were scheduled to testify on June 6 before an NLRB hearing. But on June 1, the hospital agreed, as part of the settlement with CNA, to set aside the results of last year’s election and allow the nurses to move forward with a new election.

“We have the best nurses in the world and we continue to respect all of their rights, including their right to be represented by a union, should they so choose,” said Huntington public relations director Clark.

If you’re wondering whether there’s a connection between these two news stories—the 11 deaths and the union battle at hospital—wonder no longer. There is.

Sources among nurses and CNAbelieve that the hospital knew that the deaths were due in part to its negligence in sterilizing its scopes—and its efforts to keep them secret—was about to go public, because a Los Angeles Times reporter had been asking questions. Huntington signed the settlement agreement with CNA on May 31. The Times’ first story about the scopes scandal came out the next day.

Were Huntington’s top executives worried about this double whammy of news stories about the hospital’s self-inflicted wounds? Better to settle with the union than to expose themselves to more negative publicity at the NLRB hearing, where nurses were prepared to testify about the hospital’s outrageous and costly efforts to frighten and intimidate them from organizing and voting for the union. An administrative law judge was slated to review 42 objections to the 2015 election. These included the 175 challenged ballots that led to an inconclusive election result, the firing of Shin and Lin, and other labor law violations committed by Huntington administrators. The NLRB had anticipated a three-to-four-week hearing.

“The terms of the agreement make it clear that we have the right to speak out and that the hospital’s campaign to silence us must stop,” said Terri Korrell, who has been an RN at Huntington Memorial Hospital for 42 years.

But there’s another important missing piece to the story about the tragic deaths of 11 Huntington patients. Huntington nurses warned hospital management about the problem with unsterilized scopes, but their concerns were ignored. It wasn’t until a Huntington nurse expressed concerns to CNA—which then, protecting the nurse’s identity, notified federal health agencies and the Los Angeles Times—that Huntington removed the scopes and began taking appropriate action. This is one reason that many Huntington nurses were organizing to gain a voice in their workplace. It had to do with patient care—specifically, the hospital administration’s prioritizing of revenue over patient care.

In 2014, Huntington nurses felt that they weren’t being listened to about this and many other aspects of patient care. So they contacted CNA and began talking about organizing a union. The nurses who called CNA felt that having a union, with a collective bargaining agreement insuring an independent voice for nurses in advocating for patients, was the only way that they would be listened to regarding the erosion of patient-care conditions, including chronic short staffing and inadequate supplies.

On paper, Huntington is a “nonprofit” institution, but in reality, it operates like a large for-profit corporation. Soon after the nurses’ union drive began in May 2014, the hospital (named for Henry E. Huntington, a turn-of-the-century railroad tycoon) engaged in a nasty and expensive union-busting effort. They paid a bevy of experienced and high-priced anti-union firms and consultants—Littler Mendelson, IRI and Genevieve Clavreul of Solutions Outside the Box—to harass nurses and undercut their organizing efforts. Managers at the hospital interrogated nurses about their union activity, required nurses to attend anti-union “captive audience” meetings and denied pro-union nurses access to the hospital when they were off-duty and wanted to discuss union matters.

When pro-union nurses and community allies, including a number of prominent local clergy, were meeting in the cafeteria, hospital security staff told them to remove their literature from the tables, but didn’t say anything to a group of anti-union staff at the other side of the cafeteria who had their own materials. One of the hospital’s security staff took photos of a pro-union nurse as she passed out leaflets on the public sidewalk outside the hospital. The hospital arbitrarily switched the retirement date of one nurse who had worked at Huntington for 31 years—and who was an outspoken union supporter—so she wouldn’t be able to vote in the union election last April.

Not all the nurses were initially sympathetic to the idea of unionizing. One of the reluctant nurses was Shin, who worked in the intensive care unit. Shin considered Huntington Hospital her second home. Her mother has worked there as a nurse for over 30 years. She was born at the hospital, attended its day care center and volunteered there when she was in high school. She worked as a nurse’s aide in Huntington’s ICU before becoming an RN. The family volunteers their dog at the hospital as a therapy dog.

“I was close with my mom’s coworkers. I loved Huntington,” Shin recalled. “I knew I wanted to go into nursing.”

Given her strong ties to the hospital, Shin was thrilled when she was hired at Huntington five years ago after graduating from the nursing program at California State University in Los Angeles. She worked hard, made close friends among her fellow nurses and enjoyed caring for her patients.

“I was outspoken about patient safety,” Shin said. “In nursing school, I learned that a lot of hospitals use lift teams to help patients turn over or get out of bed, so nurses don’t have to strain or hurt their backs. I gave my manager some research about this, but nothing happened. When we were short on linens or IV pumps, I mentioned it to my manager. But the problem continued. I thought the hospital was jeopardizing patient care, so I said something.”

Her words went unheard.

“To cut expenses, the hospital began rationing supplies, like bed linens and patient gowns,” Shin explained. “Many of our patients in the ICU have very compromised immune systems so the risk of infection is very high. It is absolutely essential that we have adequate supplies of clean linens, yet the hospital is intent on limiting these basic necessities.”

Nurses say that patient care standards at Huntington have eroded, compromised by cuts in nursing as well as support staff. Nurses have been forced to do more work with less help. They were made to do more admissions, more transportations of patients and more housekeeping tasks because of hospital cutbacks in these areas. The unsterilized scopes were among the many issues that nurses brought to Huntington management’s attention.

Thanks to CNA’s efforts, California is the only state in the country to enact a law mandating the ratio of nurses to patients in acute care facilities, which Huntington and other hospitals opposed before it was passed by the California Legislature and signed by Gov. Gray Davis in 1999. The law took effect in 2004, giving hospitals five years to phase in the changes. Nurses report that Huntington has repeatedly violated the nurse-to-patient ratio law, endangering patient safety.

Even so, when some of her colleagues contacted CNA to help them organize a union at Huntington, Shin had doubts.

“At first I wasn’t sure it was a good idea,” she said. “I went to some informational meetings. But I soon realized that we needed a collective voice to be advocates for ourselves and our patients. I’m not afraid to stand up for what I believe is right.”

Shin became a visible leader in the union drive. Before and after work, she met with fellow nurses—in their homes, coffee shops and outside the hospital—to encourage them to support the unionization effort. She was one of three Huntington nurses whose photo appeared on a CNA-sponsored ad on public buses running throughout the Pasadena area. “Save one life, you’re a hero,” the ad said. “Save a hundred lives, and you’re a nurse.”

Last July 26, she spoke out at a public community forum at a local church and at a news conference on the need to improve conditions at the hospital, joined by many local elected officials and community leaders who supported the nurses’ right to organize. A few days later, she was quoted in a local newspaper about conditions at Huntington Hospital and management’s expensive union-busting campaign.

Shin was suspended a week after the article was published and fired several weeks later, despite her long-term ties to the hospital and her excellent performance evaluations.

“I put my whole soul into caring for my patients, and management knows this. At Huntington, I worked as a nurse educator and sat on a committee of nurse leaders who bring patient care concerns to management. I have special training in trauma and open heart,” Shin said. “I care deeply about providing the best possible care, and that’s exactly why I spoke up at the community forum—to help ensure that RNs are supported in providing top-quality, safe care.”

“The next thing I knew, I was fired,” she said. “They tried to silence nurses. They tried to intimidate other nurses from speaking out. It’s wrong.”

On election day, the hospital received 539 votes to the union’s 445, but 175 votes were disputed, leaving the final results inconclusive. In addition, CNA filed dozens of objections to management’s illegal conduct during the election period. As a result, the NLRB did not certify the results.

CNA filed many “unfair labor practice” charges against the hospital with the NLRB, including Shin’s firing and other efforts to suppress voting and otherwise rig the outcome of the election. CNA asked the NLRB to seek a federal court injunction to force Huntington to rehire Almada and Lin. In January, the federal agency found that there was enough evidence to show that Huntington had illegally terminated Shin and Lin for their union involvement.

The nurses intend to continue their efforts to win representation with CNA in the near future. They plan to wage another union campaign, and they hope that Huntington will abide by the settlement agreement to obey the law and refrain from hostile intimidation tactics so that the election will take place on a level playing field.

The settlement “is an enormous breakthrough for all Huntington RNs who have worked hard to seek union representation and stood up valiantly for justice in the face of HMH administration’s illegal and immoral campaign,” CNA President Malinda Markowitz said. “Management is finally accepting reality. We nurses deserve a place at the table. Our voices deserve to be heard. In order to be patient-care advocates, we need the protection of a union to fight for our patients.”

The experience had a profound impact on Shin, who was raised in a conservative family and had no prior involvement with activism of any kind. Last October, Shin was invited to the White House Summit on Worker Voice because of her leadership role in the union drive at Huntington. She presented a stethoscope to President Obama on behalf of her fellow nurses and the California Nurses Association. Engraved on the stethoscope was the message: “Listen to Nurses.”

“Watching the courage of my fellow nurses as they dealt with the hospital’s anti-union campaign, and seeing activists from other unions and from the community lend their support, really opened my eyes and strengthened my resolve to fight for workers’ rights and patient care,” she said.

Shin was thrilled by the CNA-Huntington settlement, which she called a “huge success for Huntington nurses.” But she decided to resign from Huntington and continue her nursing career at Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California, a CNA-represented hospital nearby.

“For the past six months, I’ve been working at Keck USC, a hospital where RNs enjoy a CNA contract,” she explained. “Huntington RNs deserve the same protections and benefits that RNs enjoy under CNA contracts. I am committed to supporting my former HMH colleagues with their quest to win union protection. I’ll be there each and every step of the way.”

Underlying the scopes scandal and the hospital’s illegal anti-union efforts is a larger problem that isn’t unique to Huntington. At many hospitals, nurses try to alert management about issues with patient care and management blows them off or retaliates. This is emblematic of the corporatization of health care—pushing for profit at patients’ expense. Hospitals like Huntington spend large sums of money in certain areas, while cutting back on areas that support safe patient care. The difference at Huntington is that nurses, unlike the majority of California hospitals, do not yet have a powerful independent voice through union representation, leaving management’s priorities unchallenged.

Since 2010, for example, Huntington has increased the prices it charges for its services 16 percent faster than its costs have increased. In other words, the hospital seeks to boost its bottom line at the expense of patient care. During that same period, the hospital has received almost $2.5 billion in revenue from patients and had a net income of almost $87 million.

On a day-to-day basis, Huntington is run by longtime CEO Steve Ralph, who earned $3.9 million in 2014 according to its most recent 990 form submitted to the Internal Revenue Service. . (Huntington’s PR director refused to provide Ralph’s current compensation). But the hospital’s broad policies and direction are shaped by its board of directors, who include doctors, business people and civic leaders. Nurses and other employees, patients and their families, and community members have a right to hold the board accountable for the hospital’s patient-care problems as well as for its expensive and illegal anti-union campaign.

According to the hospital’s website [[http://ourstory.huntingtonhospital.com/ ]] and press releases, Huntington’s board of directors [[ http://www.huntingtonhospital.com/Resource.ashx?sn=BoardofDirectors ]] include: Paul Ouyang (chairman); Jaynie Studenmund (vice chairman); Stephen Ralph (president and CEO); Sharon Arthofer; former Pasadena Mayor Bill Bogaard; Wayne Brandt; Louise Bryson; James Buese, M.D.; Michelle Chino; Reed Gardiner; Armando Gonzalez; Christopher Hedley, M.D.; R. Scott Jenkins; Paul Johnson; David Kirchheimer; Ellen Lee; Lolita Lopez; Lois Matthews; Allen Mathies Jr., M.D.; John Mothershead; Elizabeth Olson; Kathleen Podley; James Shankwiler, M.D.; John Siciliano; Rosemary Simmons; K. Edmund Tse, M.D.; and Deborah Williams.

Americans view nurses more favorably than any other profession. Nurses have ranked No. 1 in the Gallup Poll’s “honesty and ethics” survey every year but one since 1999. (The exception is 2001, when firefighters topped the list, shortly after the September 11 terrorist attacks). Despite this, hospitals like Huntington refuse to grant nurses the dignity and respect that they deserve.

If nurses had union protection and did not have to fear retaliation for voicing concerns about patient safety at their hospital, would 11 innocent patients have died? The question lingers with many people. Huntington nurses want the hospital to return to its founding mission: to provide quality and safe patient care.

Over the past two years, Huntington nurses and community members alike have had to endure an aggressive anti-union campaign of harassment, intimidation, surveillance, bullying and wrongful termination—a campaign launched with the Huntington administration’s blessing. This costly battle has been waged against nurses who simply want to exercise their federally protected rights to organize a union and, more importantly, to uphold their responsibility to protect the sick and vulnerable admitted as patients under their care.

(Peter Dreier is professor of politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His most recent book is The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame.)

-cw

Although these new features are designed to increase safety, Waze can still be extremely distracting for drivers. First launched in Israel, it lets you chat with nearby drivers, see traffic reports from other Waze users and chart your own route. Then it provides real-time navigation and alerts you to nearby congestion, car accidents, speed traps, construction zones, potholes, stalled vehicles and/or unsafe weather conditions. The app does have a safety feature built in to ask if there is a passenger with you who is using the app, but you have to wonder how many people say yes even when they’re alone. If they engage in the chat feature, they are essentially texting while driving, which is illegal in California and over 30 other states.

Although these new features are designed to increase safety, Waze can still be extremely distracting for drivers. First launched in Israel, it lets you chat with nearby drivers, see traffic reports from other Waze users and chart your own route. Then it provides real-time navigation and alerts you to nearby congestion, car accidents, speed traps, construction zones, potholes, stalled vehicles and/or unsafe weather conditions. The app does have a safety feature built in to ask if there is a passenger with you who is using the app, but you have to wonder how many people say yes even when they’re alone. If they engage in the chat feature, they are essentially texting while driving, which is illegal in California and over 30 other states.

Persistently vibrant --Southern California’s creative economy, as Cary McWilliams noted 60 years ago, came as a result of some very good fortune – largely the exodus of movie producers seeking respite from New York process servers and close proximity to the Mexican border. Once there, they discovered the possibilities of shooting films and living in an ideal climate.

Persistently vibrant --Southern California’s creative economy, as Cary McWilliams noted 60 years ago, came as a result of some very good fortune – largely the exodus of movie producers seeking respite from New York process servers and close proximity to the Mexican border. Once there, they discovered the possibilities of shooting films and living in an ideal climate.

Perez (photo left) explained that there are some homeless who don’t even bother to go to a shelter or church where distributions of food are offered because of their circumstances, “We targeted those who don’t have access, for whatever reason, and give them a break from their harsh reality by bringing some hope into their lives.”

Perez (photo left) explained that there are some homeless who don’t even bother to go to a shelter or church where distributions of food are offered because of their circumstances, “We targeted those who don’t have access, for whatever reason, and give them a break from their harsh reality by bringing some hope into their lives.”