CommentsPLANNING WATCH-Those who look at Los Angeles with eyes wide open see cracked and pot-holed streets, broken sidewalks, and a shrinking urban forest.

Curbs and gutters are filled with weeds and litter. Entire neighborhoods are still waiting for streetlights and street sweeping. City crews can barely keep up with bursting water mains and electric grid blackouts. The sun never sets on private utility crews installing 5G towers, upgrading sagging telecommunication cables attached to LADWP utility poles, and repairing natural gas pipelines.

In the midst of this accumulating urban decay are billions devoted to new mass transit lines, but not to the basic first-last mile public improvements that increase transit ridership. These include station interfaces for busses; parking facilities for cars, bicycles, and scooters; wayfaring signs and shade trees for pedestrians; new phone apps and bus shelters for transit riders; reduced or totally eliminated fares for passengers; and low priced transit-oriented housing for the transit dependent.

It is particularly galling that the many billions that METRO spends on new subway lines, like Wilshire Boulevard’s Purple Line Extension, exclude these first-last mile public improvements. In fact, METRO consistently violates its own adopted policies and ignores LA City Planning’s Mobility Hubs and Complete Streets manuals for implementing essential California transportation laws.

How do we explain this omission, that the billions METRO and local cities spend on mass transit do not include the basic infrastructure improvements that expand ridership? So far, the best explanation comes from Allen Whitt, in his classic Urban Elites and Mass Transportation: The Dialectics of Power. Whitt’s careful analysis of the early years of BART and MetroRail concludes that the best explanation for mass transit decisions is to increase the market value of less profitable commercial real estate. Whitt argues that mass transit agencies select transit alignments to restore value to older commercial parcels, not to increase transit ridership.

Whitt’s insights are just as valid in 2020s as they were in the 1980s. His study allows us to understand why METRO has spent nearly a billion dollars per mile to extend the Purple Line subway from Koreatown to the Veterans Hospital – without including first-last mile public improvements. Section 1, from Western Avenue to LaCienega Boulevard, does not even have a first-last mile plan, while Sections 2 and 3, from LaCienega to the Veterans Hospital, have first-last mile plans, but no funds to implement them.

As for LA City Planning, it claimed that an ordinance to up-zone parcels within a half-mile of the Purple Line Extension’s route was the secret sauce to increase transit ridership. Even though City Planning shelved that plan, it still took enormous community pressure to persuade METRO to plan for local public improvements, a task they have not yet completed despite a decade of work on the Purple Line Extension.

When Section 1 of the new subway opens in 2023, despite the subway’s $9.3 billion price tag, it will not have parking structures, interfaces for busses and cars, repaired sidewalks, ADA curb cuts, streetscape, shade trees, upgraded lighting, bicycle and scooter infrastructure, and such basic amenities as kiosks.

Rendering of Crenshaw Rail Extension Aerial alternatives for San Vicente, LaCienega, and LaBrea Avenues.

Rendering of Crenshaw Rail Extension Aerial alternatives for San Vicente, LaCienega, and LaBrea Avenues.

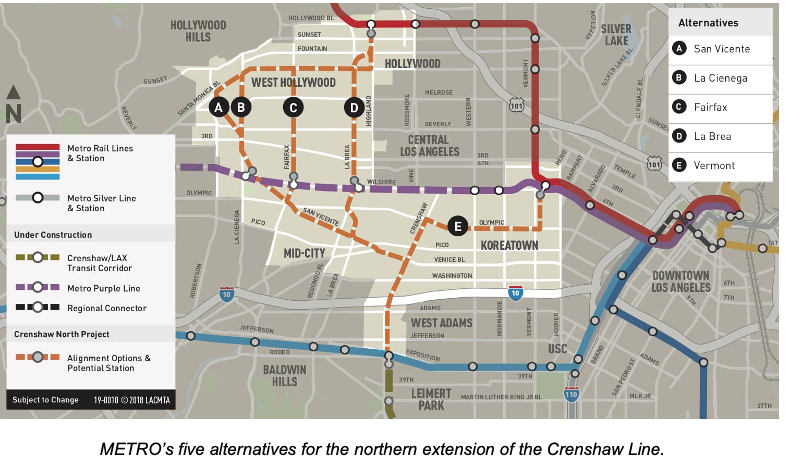

Northern Extension of the Crenshaw Line: This gross negligence is hardly unique. METRO continues to repeat the same mistake, this time for the extension of the future Crenshaw Line through LA’s Miracle Mile and Fairfax neighborhoods to West Hollywood.

Could it be that there is a much cheaper alternative to a new transit line that will cost many billions by the time construction ends in 2047. The answer is an emphatic yes. It is the five mile long My Figueroa project. Its total cost was $20 million or $4 million per mile. It involved an extensive Complete Streets makeover of the commercial corridor connecting downtown Los Angeles to USC. In current dollars the cost would be closer to $10 million per mile.

If METRO took this approach to the extension of the yet unbuilt Crenshaw Line to West Hollywood, it could save billions. The cumulative length of the five METRO alternatives, already under environmental review, total 32 miles. METRO could minimally upgrade each alternative to the My Figueroa standard for a total of $320 million dollars (32 miles X $10,000,000/mile). This would include street lighting, dedicated bus lanes, bicycle and scooter infrastructure, sidewalk and street reconstruction, bus shelters with real time arrival signage, street tree planting and maintenance, streetscape, and wayfaring signs. It could also be linked to the elimination of bus and subway fares, a program that METRO is carefully studying to increase ridership. So far, Metro has allocated $2.24 billion to the Crenshaw Line’s northern extension. If or when it opens 25 years from now, the final cost will, of course, be much higher.

The advantages of the Complete Streets approach to the Crenshaw line’s alternative routes is that they are substantially cheaper and could be quickly implemented. These upgraded corridors would provide appealing non-automobile alternatives to local residents, while not pushing the area’s already maxed out infrastructure and public service systems to the breaking point.

Final Lesson. Transportation projects, like this, should not be piecemealed, oblivious to the General Plan’s Mobility Element 2035 and nearby mega-projects, such as the Purple Line subway. Instead, smaller proposals should be comprehensively planned well in advance, not thrust upon resentful residents as last minute ad hoc projects, such as those recently proposed for San Vicente Boulevard, 6th Street, Third Street, and Melrose Avenue. Piecemealing is the opposite of planning. It is expensive and ineffective. It stems from political pressure generated by local boosters unconcerned about long term consequences.

This is why the Crenshaw Line’s northern extension should be replaced by a Complete Streets approach modeled after My Figueroa. While some West Hollywood Chamber of Commerce types might become sore losers, the public benefits will far outweigh a major misallocation of public resources.

(Dick Platkin is a former Los Angeles city planner who reports on local planning issues for CityWatch. He serves on the board of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA) and co-chairs the new Greater Fairfax Residents Association. Previous Planning Watch columns are available at the CityWatchLA archives. Please send questions and corrections to [email protected].) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.