CommentsPLATKIN ON PLANNING-The old Urban Renewal. Urban renewal was the grand strategy of the Federal Government in the post-WWII war era to reconstruct large sections of American cities through local agencies, such as California’s Community Redevelopment Agencies.

The critical laws adopted by Congress were the Housing Acts of 1949 and 1954, the Highway Act of 1956, and the New Communities Act of 1968. Through Federal subsidies, entire neighborhoods were acquired through each city’s power of eminent domain. Then came the evictions of local residents, followed by the bulldozers and wrecking balls.

After the local agencies assembled many small parcels into larger ones, large real estate investors were invited in, again with government subsidies, to rebuild these older neighborhoods for upscale commercial tenants and occasional high-rise apartments with subsidized rents that are now expiring.

In Los Angeles, a famous historic area, Bunker Hill, totally disappeared. Your only recourse to see what once thrived there are film noir movies, such as Cross Cross (1949). The City replaced this neighborhood with the Harbor Freeway and the new financial district, office and bank buildings, and high-end hotels on Figueroa and Flower Street.

Urban renewal’s primary rationale was the elimination of “blighted” neighborhoods, and these programs were successful in leveling these older, poorer neighborhoods, at least in locations where investors could take advantage of their ideal location, such as Little Tokyo in downtown Los Angeles.

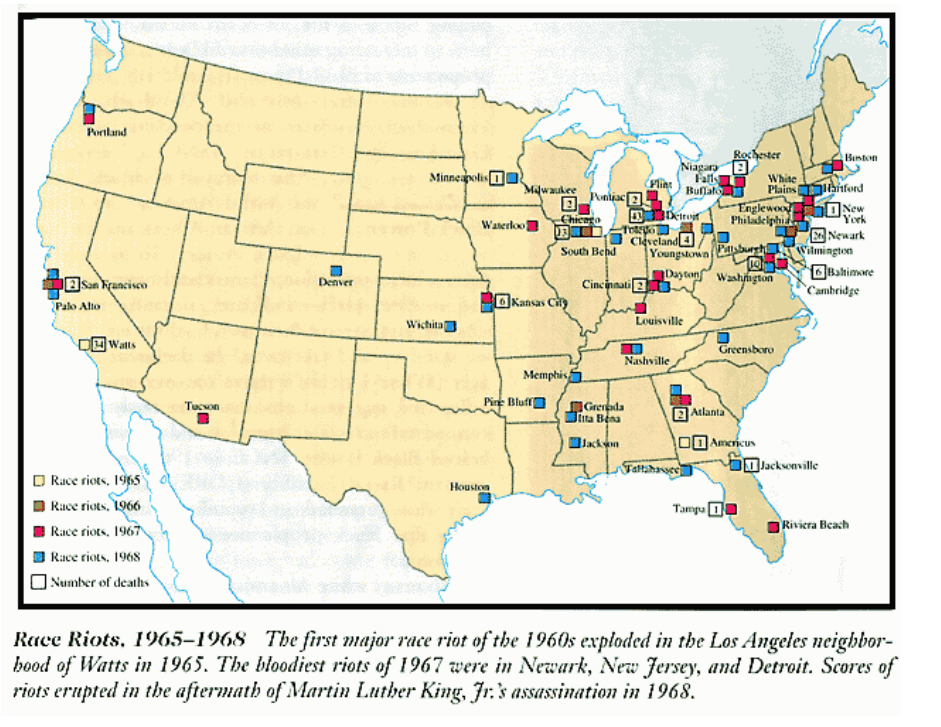

But urban renewal had two critical blind spots. First, by removing the residents from these neighborhoods, it simply pushed low-income people out to other neighborhoods. This is why, especially in cities like New York, writer James Baldwin called urban renewal Negro Removal. By shoving the poor to other neighborhoods, urban renewal did not address the root causes of blight, which was racism and economic inequality. In fact, it led to massive displacement and impoverishment, one of the factors responsible for the frequent ghetto rebellions in the United States between 1964-1969, including Los Angeles in 1965.

The other blind spot was taxation. The redevelopment agencies gobbled up an increasing share of local tax revenues through tax increment financing. The increased value and tax payments for redeveloped neighborhoods went into the coffers of redevelopment agencies, not cities.

For these and other reasons urban renewal was gradually phased out. In California its end finally came in 2011-2012 through the actions of the California State Legislature and Supreme Court.

The new Urban Renewal is targeted upzoning: The official end of urban renewal in California did not, however, end informal and formal support by state and local government aid to investors interested in easy access to desirable locations in older neighborhoods for their grandiose projects. This is where Scott Wiener and his champions, such as YIMBY California, which authored his previous proposal, SB 827, and played a major role in SB 827 2.0, the recently released SB 50.

There are, however, major differences between the old urban renewal and its reincarnation through schemes to up-zone many urban neighborhoods, without any parallel upgrades of supportive municipal services and infrastructure.

The old version depended on legislation from the Federal Government, combined with the power of local government to acquire large blocks of real estate through eminent domain.

The new version also works through government, but only at the state and local level. Instead of creating new agencies employing many architects, designers, civil engineers, and city planners, the new version largely relies on market forces, abetted by the deregulation of zoning and environmental review. It guiding theory is a pipe dream that unregulated market forces can be harnessed to build affordable housing, increase transit ridership, and reduce Green House Gases. If we just let investors maximize their profits through speculation in urban real estate, this rising tide will lift all boats.

While the previous version was based on a grand vision of rebuilding entire neighborhoods, the new version has settled for a chaotic parcel-by-parcel approach.

While the old version also used highways and affordable housing as its pretext for acquiring older parcels and evicting residents, the new version has shifted its rational from highways to mass transit. And, instead of building government operated affordable housing, the new version calls for a small percentage of either mandatory or voluntary affordable housing in expensive market projects -- without any on-site inspections.

The new version also has two other justifications that the older version did not invoke: increasing transit ridership and, therefore, reducing the generation of the Green House Gases responsible for climate change. But, just as the older version used the elimination of blight as a pretext, as it shunted the poor to other neighborhoods, the new version targets neighborhoods that its alleges are not suitable for transit ridership, displacing local residents through evictions instead of eminent domain.

But, like the urban renewal, this is only a cover story for government intervention to speed up the gentrification process. It allows real estate investors to get access to prime locations now occupied by low-income residents. Furthermore, the current rationale is so preposterous that it could never withstand any type of independent assessment to verify its rationales or that it achieves its stated goals.

Whether the new urban renewal proceeds at the local level through real estate scams the like the Purple Line Extension “transit neighborhood plan” or at the state level through Scott Wiener’s SB 827 and his SB 50, there is no evidence that these programs create more than a sliver of short-term affordable housing, or that they reduce the generation of Green House Gases. Any monitoring program would quickly reveal that these are totally bogus claims, which is why the new urban renewal never monitors itself. Once it achieves its real goal, upzoning, the process ends, and these generous gifts to developers are locked into place.

Other deceptions supporting the new urban renewal would also dissolve under scrutiny. It advocates, like its lead torchbearer, Scott Wiener, repeatedly claim that their upzoning schemes will create affordable housing by “supply-and-demand,” conveniently forgetting that this “economic law” only works when investors make high profits. It never works if investors lose their shirts to build and/or rent affordable apartments.

The other unsupported claim by Wiener and his followers is that the expensive housing they lobby hard for will become affordable 25 years from now through filtering. When pressed for examples where this has happened, they can never pin point any locations. For example, they are unable to identify any previously expensive housing that is now affordable in Los Angeles because if does not exist.

As the politicians, the academics, and the media ballyhoo SB 50, each bubble will be easily pierced by a simple request, “Show us the evidence.”

This will lead to the demise of the new urban renewal, so it can join the old renewal on library shelves reserved for failed urban programs.

(Dick Platkin is former Los Angeles city planner, who reports on local planning controversies for CityWatchLA. Please send any comments or correction to [email protected].) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.