CommentsPlatkin on Planning: According to acclaimed investigative journalist, I.F. Stone, all governments lie. Now, looking back on his dogged reporting, it would be great if we could ask him one key question: “How do they lie?”

We know that some lies are nothing more than impulsive quips from our current President.

Sometimes, though, the lies are far more elaborate, and a new documentary about I.F. Stone, “All Government Lie: Truth, Deception, and the Spirit of I.F. Stone,” highlights many such lies that investigative journalists disproved, such as:

- The Johnson Administration lied to Congress about a North Vietnamese patrol boat firing on two U.S. destroyers, in order to escalate the Vietnam War through the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

- President Richard Nixon stated, “In all of my years in public life, I have never obstructed justice.”

- To justify the second Iraq war, Secretary of State Colin Powell told the UN Security Council, “We are giving you facts and conclusions based on solid intelligence.”

Sometimes, though, the lies are subtler, spun by officials who exclude key information to cover-up government missteps. I.F. Stone called this deception, and it was on full display at a recent City Planning slide show to pitch the proposed Purple Line Extension Transit Neighborhood Plan. This presentation, to the Longview Neighborhood Association on October 23, 2018, buried critical background information in order to “make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear.”

What follows is a careful look at some of the deceptions used at that event to sell what I previously wrote is really a real estate scam. It indicates that local skullduggery may be far more widespread that we imagine. Apologies in advance for walking you through the weeds to shine some light on this presentation.

Presentation Claim: “Global temperatures are rising as a result of emissions of Greenhouse gases (GHGs) – and transportation is the main source of emissions in California.”

Totally true, but there is no evidence that the proposed Purple Line Transit Neighborhood Plan (TNP) will reduce the generation of Greenhouse Gases. At best, it will have no impact on the vulnerable communities near the two new Purple Line stations: Wilshire/LaBrea and Fairfax/LaBrea. At worst, this plan will be “growth inducing,” a polite way to say it will increase the generation of Green House Gases. The new buildings that the TNP fosters will be auto-centric high-rise structures. Based on recently opened apartment buildings, the new rents will be approximately $4,500 per month for a one-bedroom apartment. Such excessive rents ensure that new tenants will be drawn from the demographic category most likely to own and drive cars, the well off. This gentrification process will also displace existing residents, many of whom are far more likely to take buses or future Purple Line subways than newcomers.

Presentation Claim: “Transit use, especially rail, shows significant GHG emission savings over driving alone.”

Correct again, but this truism has no connection to the proposed Transit Neighborhood Plan (TNP). The TNP does not encourage existing residents to switch from cars to buses and subways. Rather, its approach is to replace existing buildings and residents with new luxury buildings and their well-to-do tenants. Not only will the embedded carbon in the existing buildings be lost forever, but considerable energy and resources will also be required to build new luxury high-rise apartments and commercial buildings in their place.

Once built, most of their new affluent residents, employees, and visitors will rely on cars and Ubers for their trips to and from the Fairfax, Beverly Grove, Miracle Mile, Museum Row, San Vicente, Little Ethiopia, and LaBrea neighborhoods. Not only will driving continue, but it could also increase because ride-hailing services, like Lyft, double the number of trips compared to driving alone. One round-trip is necessary to arrive, and a second round-trip is necessary to leave.

Presentation Claim: State law and regional policies require cities to direct growth to transit areas to reduce GHGs.

California Assembly Bill 32 and Senate Bill 375, which are referenced in this claim, do not supersede the Los Angeles General Plan and its implementation through zoning and capital improvements. The Los Angeles General Plan remains the city’s “constitution” and the proposed Purple Line TNP conflicts with it in three major ways, as well as with AB 32 and SB 375.

First, L.A.’s adopted General Plan Framework Element requires a comprehensive plan monitoring program and annual report, which should include Green House Gas levels. But, the TNP does not have any monitoring for air pollution and transportation patterns. It, therefore, has no way to determine if its upzoning scheme reduces driving or Green House Gas levels. Furthermore, the TNP has no mechanism to rescind its zone changes if, as I predict, they increase Green House Gas levels.

Second, the General Plan Framework, through its Objective 3.3, requires the City of Los Angeles to demonstrate adequate infrastructure and public services when it up-zones private parcels. This includes such features as a well-maintained urban forest, walkable sidewalks, and safe bike lanes, all critical components to meet the Green House Gas reduction goals of AB 32 and SB 375, and the exact programs that the Purple Line TNP bypasses.

Third, LA’s General Plan is growth neutral, and the Purple Line TNP will be a deliberate growth-inducing zoning ordinance. Its new zoning is intended to spur the construction of larger, taller, denser in-fill buildings. Their price points will ensure that they are auto-centric, spewing out more Green House Gases than the buildings they replace.

Presentation Claim: LA’s 1970 Concept Plan envisioned a system of centers with high-density development linked by transit and surrounded by nodes that step-down in intensity.

This is absolutely true, but L.A.’s 1970 Concept Plan was only an adopted General Plan policy document. It was never implemented through either zoning or capital improvements. LA’s zoning laws remained separate from its General Plan until the California State Legislature adopted the AB 283 zoning consistency program in 1979 and then imposed it on Los Angeles. This program only concluded in 1991, when it set the direction for the Concept Plan’s successor, the General Plan Framework Element, adopted in 1996.

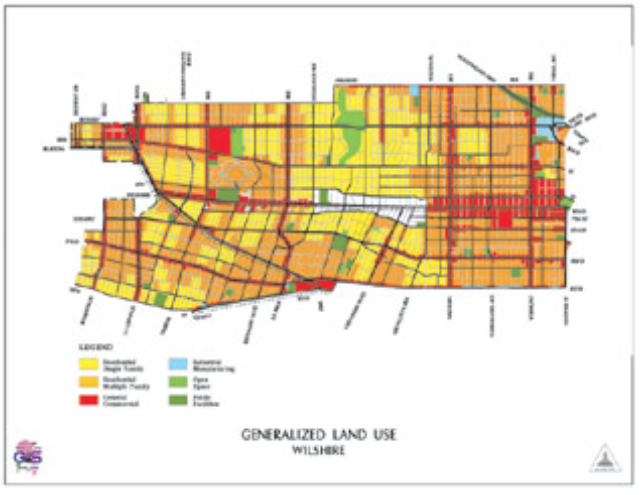

This planning process included the 2002update of the Wilshire Community Plan. This update implemented the policies of the 1970 Concept Plan and the 1996 General Plan Framework through ordinances that established high density, high intensity zoning on Wilshire Boulevard. When these areas subsequently became the Red and Purple Line Subway Corridor, the Wilshire Community Plan also implemented the General Plan’s transportation policies.

This implementation program included a complex 389-page land use ordinance that upzoned Wilshire Boulevard and adjacent neighborhoods, per the General Plan’s policies. For example, it established regional centers in the Miracle Mile, Koreatown, and Vermont neighborhoods. Furthermore, the 2002 upzoning ordinance led to the construction of many new apartment buildings at these regional centers, plus adjacent areas with stepped-down zoning.

What this zoning and its resulting transit-oriented residential construction boom has not led to, however, is increased transit ridership and reduced Green House Gas levels. Why? Because the many new apartment buildings constructed at the regional centers and adjacent areas are expensive. Unlike existing Wilshire area residents displaced through gentrification, the new tenants rarely use transit. This is the obvious explanation for the Red and Purple Line’s declining transit ridership despite up-zoning ordinances and new apartment construction.

Presentation Claim: The 1986 MetroRail station plans proposed Floor Area Ratios as high as 13:1.

In the mid-1980s the Southern California Rapid Transit District, now renamed METRO, commission the Los Angeles Department of City Planning to prepare13 Specific Plans for the entire subway alignment, which then included Wilshire Boulevard through Fairfax Avenue. These Specific Plans included the Wilshire/LaBrea and Wilshire/Fairfax subway stations, both abandoned when METRO changed the MetroRail alignment. Unlike the current Purple Line Transit Neighborhood Plan proposal, City Planning prepared these Specific Plans through extensive community meetings, closely coordinated with the transit agency.

These older plans were also unclear on the concept of Floor Area Ratio (FAR). They sometimes considered FAR to be a height limit, as measured in the number of permitted stories. In these cases an FAR of 13.1 sometimes referred to a 13 story high-rise building, many of which have been built since 1986, even though the SCRTD changed the subway route.

Based on extensive public participation process, the Department of City Planning drafted Specific Plans for 13 original Metrorail station are. Intended to protect local communities from impacts resulting from subway operations, these plans permitted three levels of development. The first tier was based on existing transportation services. The second level was greater density contingent on the adoption of a Transportation Systems Management (TSM) Plan for each station area. Finally, higher levels of permitted development were allowed if or when the subway opened.

In contrast, the current Purple Line TNP only has one development tier, up-zoning without any affordable housing conditions. If the City Council adopts the TNP Specific Plan, its up-zoning will be permanently locked into place. It will remain untouched even if the subway is not completed, does not increase transit ridership and affordable housing, does not reduce automobile driving and Green House Gas levels, and the parallel update of the Wilshire Community Plan rejects upzoning.

Another critical difference is that the Department of City Planning prepared Draft Environmental Impact Reports (DEIRs) for the original MetroRail Specific Plans after – not before – they completed draft Specific Plans. In no cases, did the Department of City Planning undertake the environmental review of a draft Specific Plan that did not yet exist.

Presentation Claim: The Purple Line Transit Neighborhood Plan is part of a larger planning process that links the three new subway stations to LA’s General Plan and its Community Plans.

First, the Purple Line Transit Neighborhood Plan only applies to the two future subways stations in the Los Angeles. The Wilshire/LaCienega station is in Beverly Hills, which is totally relying on existing plans and zoning for transit area planning. No Beverly Hills Wilshire/LaCienega Transit Neighborhood Plan is in the works.

Second, local communities in the Transit Neighborhood Plan area have proposed that the forthcoming update of the Wilshire Community Plan include land use planning for all subway stations, both existing and under construction. This approach would fold the TNP into the Community Plan update process.

Third, the Department of City Planning is preparing the TNP out of sequence. To do it right, City Planning must first update the citywide General Plan Elements, most of which are 25 to 50 years old. This comprehensive update also should including an optional element to address Green House Gases and climate change, per the 2017 California General Plan Guidelines. City Hall should then update the 35 Community Plans and two District Plans that comprise the General Plan’s Land Use Element. In doing so, these updates should full comply with California State law by carefully adhering to the Complete Streets Guidelines prominently placed on City Planning’s home page.

Fourth, unlike the TNP, these updates should down-zone, not up-zone transit adjacent parcels to compel real estate developers to include affordable housing in their projects.

Presentation Claim: City Planning’s October 23 presentation faithfully summarized what the public wanted for neighborhoods near the future subway stations.

What the presentation neglected to mention, however, is that TNP totally rejects the public’s recommendations.

- The public wants neighborhood serving uses, but once the TNP up-zones commercial properties, their market values will soar, along with rents for apartments and stores. Existing and potential neighborhood uses, such as pharmacies, tailors, dry cleaners, optometrists, and small restaurants will be priced out of the Miracle Mile and adjacent neighborhoods.

- The public wants open space and green space, but the TNP will only be a zoning ordinance. Neither METRO or the City of Los Angeles have anteed up any funding for pocket parks, playgrounds, shade trees, median strips, or landscaping. At $700 million per mile, there was no thought or budget allocations for these public improvements.

- The public wants bicycle amenities, but the TNP does not include any bicycle lanes or bicycle parking. Even such a no brainer as locating METRO bike sharing stations at subway portals and bus stops slipped through the cracks. As for dockless scooters, without the construction of bicycle lanes and parking areas, they will continue to block sidewalks and impede pedestrians walking to subway stations and bus stops.

- The public wants mobility options, but the TNP does not give it to them. In addition to ignoring bicycle infrastructure and bike sharing, there is no planning or budget to repave sidewalks, install ADA curb cuts, plant shade trees, redesign intersections, upgrade street lighting, install bus shelters, or prepare real time transit apps for smart phones.

- The public wants adequate parking, but the TNP does not include any new parking structures. The best option for subway riders would be to stow their cars at museum parking lots near the Wilshire/Fairfax station, ponying up between $16 to $20 per day for easy subway access.

- The public wants safe sidewalks and cross walks with pedestrian-friendly design, but the TNP has no proposals or budget for intersection improvements or reconstructing sidewalks to higher ADA standards, despite legal settlement imposed on the City of Los Angeles.

- The public wants social services and affordable housing, but there is no METRO or municipal budget for social services. As for affordable housing, the TNP has no mandatory affordable housing requirements, and its upzoning bonuses have no strings attached.

These deceptions and their debunking won’t shock Angelinos involved in day-to-day struggles over real estate projects and City ordinances. At this point, though, most other Angeles don’t have the time and sense of dread that keeps their neighbors up late at night, working through the verbal subterfuges that are the building blocks of local government deception.

This column is dedicated to both groups of Angelinos.

(Dick Platkin is a former Los Angeles city planner who reports on local city planning controversies for CityWatchLA. Please send any questions or corrections to [email protected].)

-cw