Comments

iAUDIT! - In a previous column, I described the failures of Los Angeles’ homeless shelter system. Shelters, which are supposed to be the gateways to permanent housing, suffer from a plethora of problems, from unsanitary conditions to chronic understaffing. Due to these problems, the transfer rate is dismally low, between 14 and 20 percent. Today’s column will look at what happens to the few people lucky enough to gain some kind of permanent housing, although “lucky” may not be the appropriate word. Because, as bad as many shelters are, publicly managed housing is no better.

Before going into more detail about problems with LA’s homeless housing programs, we need to understand just how important housing is to current policy. As you might guess from the name, housing is the foundation of the Housing First approach. Based on studies, people in stable housing are more likely to benefit from services like addiction recovery and mental health counseling than those living on the street. Physical health outcomes are also better, with housed people experiencing lower incidence of serious or chronic illnesses. Housing First is the official policy of HUD and the State of California. Therefore, the City and County steer significant funding to building or acquiring and managing housing. Given the importance of housing to official policy, one would expect local agencies to devote appropriate resources to properly manage their housing projects.

Housing for homeless people can take many forms, but the two main types are interim and permanent. Interim housing includes shelters, which I’ve discussed before. Permanent housing includes:

- Permanent Supportive Housing (PSH): This is for people with a need for medical and/or mental health services, but who can live semi-independently. It may take many years for them to live completely independently (if they can at all), so the housing must be accompanied by structured and regular services. A client can live in a PSH unit indefinitely.

- Permanent Housing (PH): PH consists of a wide variety of housing types, from government-owned buildings to private apartment complexes that accept subsidy payments. Often. the city contracts with agencies like the now-defunct Skid Row Housing Trust to provide apartments, and other nonprofits provide services to tenants. A common type of permanent housing the time-limited subsidy (TLS). As the title implies, TLS units are apartments in private complexes, where the City or LAHSA pay all or part of the rent for up to two years. Those most likely to benefit from TLS programs are people who may be in temporary financial difficulty and need mid-term assistance to get back on their feet. People coming from abusive home environments also benefit from TLS. Even though the subsidy expires after two years, TLS units are considered permanent housing by HUD and other agencies.

- Another subset of permanent housing consists of single-room occupancy (SRO) housing. An SRO has private units similar to hotel rooms; rooms are private, but the building usually has shared bathrooms and shower facilities and generally prohibit in-room cooking. SRO’s were fairly common through the 1960’s, in the form of rooming houses; LA’s Bunker Hill was well-known for its many former mansions converted to boarding houses, until they were wiped out by redevelopment. Now, most remaining SRO’s are part of the network of former hotels in and around downtown LA. Many were once owned by the Skid Row Housing Trust (SRHT), a nonprofit organization that used city and other government money to acquire, renovate, and operate SRO’s for formerly homeless people.

Skid Row Housing Trust went bankrupt in 2023. As described in an LA Times article at the time, SRHT started with a shaky financial model, buying and preparing old DTLA hotels to operate as SRO’s. The complex financing system depended heavily on government subsides based on occupancy. If a unit was vacant, there was no funding. At the same time, No Barrier Housing First policies required SRHT to accept people with serious mental illness and addition problems, most of whom received no treatment or support from a broken and unaccountable system, (and don’t have to accept services when they’re offered). As the Times article described, repair costs skyrocketed as tenants caused significant damage. At the same time, the Trust lost revenue because rooms remained vacant as they awaited repairs. The result was buildings filled with people in dire need of support as maintenance and repairs fell further and further behind. Even those who didn’t need support services found themselves living in squalid conditions. After the Trust went bankrupt, the City spent millions in taxpayer money to shore up a series of receivers in an attempt to keep people housed. Despite continuing to operate, the buildings still suffer from chronic repair needs and lack of basic maintenance.

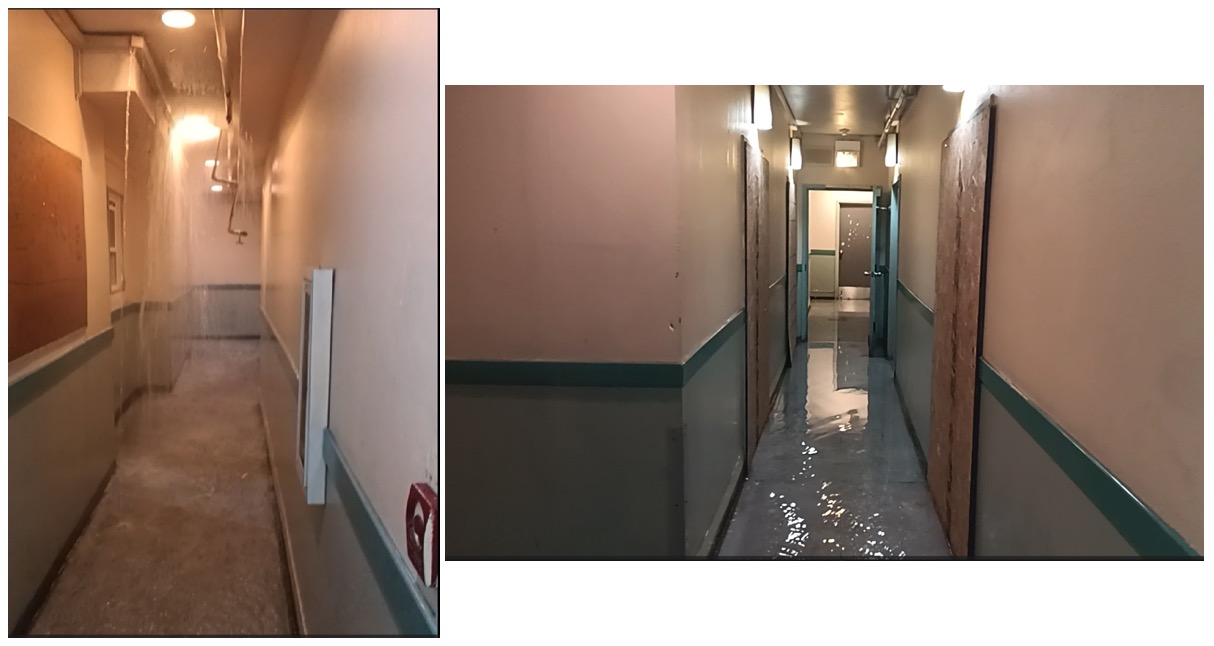

The squalor in which tenants are trapped was driven home when a formerly unhoused friend who lives in one of the SRO buildings shared photos and emails concerning his living conditions. They are shocking. The photos he sent me show peeling paint and missing door hardware, including missing locks (despite the fact many formerly unhoused people rate privacy at the top of their list for accepting housing offers). Worse, my friend shared video clips of water pouring through the ceiling from a burst pipe as the floor floods several inches deep, (see screenshots below).

In addition to the photos, my friend shared emails he sent to management, notifying them that some tenants were missing, one of whom had a brain injury and needed monitoring. Other emails noted delayed benefits for other tenants, constant turnover in building management, and repair needs ignored for weeks.

Lest you think problems are isolated to downtown SRO’s, read this column from Christopher LeGras’ All Aspect Report about his friend Brian. Brian has mental health and addiction issues, and rather than providing a housing setting with proper support services, authorities dumped Brian in a subsidized apartment and declared him “housed”. The apartment was so barren, “Spartan” would be a generous description. Worse, it overlooked a pub with outdoor seating, torturing Brian with the sound of happy people enjoying drinks while he sat alone and isolated. Little wonder he soon returned to the familiarity of the streets and disappeared into the anonymous army of the unhoused occupying LA’s dark places.

Of course, Brian isn’t the only victim of a broken system. The same structure that pays providers with no proof of performance is the same one that grants no-bid contracts to nonprofits like HOPICS, that mismanaged $140 million in taxpayer money for apartment subsidies so badly, hundreds of formerly homeless people were evicted for nonpayment.

Pulling back to look at the entirety of homelessness interventions in Los Angeles, we can see how almost nothing works as it should. The shelter system, which should act as a conduit from the streets to housing, failed to reach 20 percent transfers to housing over four years, while losing 50 percent of shelter occupants back to homelessness. Even Inside Safe, Mayor Bass’ signature program, has succeeded in permanently housing only about 24 percent of its clients, while spending nearly half a billion dollars. Of the 1,039 people in permanent housing, 410 (39 percent) are in TLS units and may return to the streets when the subsidies run out.

Measure ULA, the so-called “mansion tax” approved by voters in 2022 is another example of how poorly our public resources are being used. In a recent Westside Current article, Jaime Paige describes how only a little more than one percent of the $700 million collected has gone towards creating affordable and homeless housing. The article shows the city has spent 15 times more on running the program than it has creating housing which could alleviate the affordability and homelessness crises. Officials offered the usual raft of excuses, such as pending litigation, but one pertinent fact is the Council didn’t adopt permanent guidelines for using ULA revenue until December 2024, twenty months after voters approved the measure. Despite campaign promises for quick action, the city didn’t have clear guidelines on how the money would be spent until almost two years after its approval. And, as with all of its other homelessness and housing programs, the City has a habit of taking credit for units it hasn’t paid for. As readers may recall from my previous column on Judge Carter’s decision, reviewers found the city tool credit for creating TLS units it didn’t pay for. The Westside Current article quotes the Chair of the Council of Infill Builders as saying nearly all of 795 units the City claims are funded by ULA, were actually in the development pipeline before the measure was approved. Aas with so many other homelessness programs, leaders emphasize appearance over achievement.

What is truly frightening is this dysfunctional system may become the standard operating procedure for the County’s new homelessness program. As I wrote in a previous CityWatch column, the County may use its Housing for Health (H4H) program as a model for the homelessness system it hopes will replace LAHSA. Although the County claims H4H is a great success, the reality is that it is expensive and suffers from the same inefficiencies as other programs, primarily benefitting corporate nonprofits that have already reaped a financial windfall from LA’s homelessness system.

We can see how the unhoused are forced into a dehumanizing system of squalid shelters where their needs are largely ignored; the lucky few who are housed often find themselves abandoned in sparsely furnished apartments or in decrepit SRO’s that harken back to 19th century New York tenements. This is not the way we should be treating the most vulnerable people in our society, yet it is the way the County, among others, intends to use as a model.

Surely, we can do better.

(Tim Campbell is a resident of Westchester who spent a career in the public service and managed a municipal performance audit program. He focuses on outcomes instead of process in his iAUDIT! column for CityWatchLA.)