CommentsCALIFORNIA POLITICS--When two New York baseball teams, the Dodgers and the Giants, moved west six decades ago, their ancient cross-town rivalry merged into the equally intense – and equally long – competition between Los Angeles and San Francisco for economic, cultural and, of course, political dominance of California.

As the second half of this year’s baseball season began, the Los Angeles Dodgers were sitting on the best record in the major leagues while the San Francisco Giants, despite winning three World Series titles in this decade, had the second worst.

The Giants might not be doing well this year, but the San Francisco Bay Area’s technology-centered economy is, by any measure, red-hot and not only far surpassing the Los Angeles region’s lackluster economic performance but also, in effect, propping up the entire state.

How Los Angeles wound up eating the Bay Area’s dust, at least in economic terms, is a tale of civic and political decisions, demographic circumstance and even global politics. And with the two regions accounting for most of the state’s population and the economic output that makes it a global powerhouse, whether the stark differences widen or narrow will have a huge impact as California meanders further into the 21st century.

First, a few numbers to illustrate the whopping economic differential:

- With just 20 percent of the state’s population, the 10-county Bay Area generated a quarter of the $1.5 trillion in adjusted gross income (AGI) that Californians reported on their personal income tax returns in 2014, the last year for which complete data are available. That makes it very important for a state general fund budget that depends on income taxes for 70 percent of its revenue.

- The five-county Los Angeles region has more than twice as much population as the Bay Area – and nearly half of the state’s residents – but generated just a third of the state’s 2014 AGI. The Bay Area’s per capita AGI averaged just under $50,000, while the LA area’s was scarcely half as much. More than likely, the Bay Area’s share of income has increased since then.

- Of the state’s 10 highest median income counties in 2014, six were in the Bay Area, topped by No. 1 Marin County, at $140,681 per joint tax return, and No. 2 San Mateo at $122,415. The only Los Angeles region counties on the list were No. 9 Orange at $83,393 and No. 10 Ventura at $82,193. Los Angeles County itself was No. 25 at $64,890, markedly below the statewide median.

- Over the last nine years, since 2008, the Bay Area created nearly two-thirds of California’s 1.1 million additional jobs. It increased its share of the state’s employment to nearly a quarter – again, with just 20 percent of its population. The LA region’s job growth rate was just a third as high, and its share of total employment declined.

- In 1970, the Los Angeles area was ranked No. 1 nationally in per capita income and the Bay Area, No. 3. By 2009, after both regions had increased in population by about 50 percent, the Bay Area was No. 1 and the Los Angeles region was No. 25.

- Taxable retail sales show a similar differential. While the state as a whole saw a 17 percent growth in sales between 2006 and 2016, those in the Bay Area shot up by 26 percent and now account for nearly a quarter of the state’s retail activity, again with just 20 percent of its population.

- Finally, when the Public Policy Institute of California and the Stanford Center on Poverty and Inequality in 2013 created a new measure of poverty in California that takes into account the cost of living – particularly housing – it calculated that Los Angeles County has the state’s highest rate. Of its 10 million residents, 25.6 percent were in economic distress.

That makes Los Angeles the most impoverished county in a state that, by the Census Bureau’s similar methodology, has the nation’s highest rate of poverty. Poverty rates in Bay Area counties are, not surprisingly, among the state’s lowest, since their high housing costs, unlike those in Los Angeles, are more easily offset by high incomes.

So how did it happen that the Bay Area’s economy came to dominate the state, and the Los Angeles region, by such wide margins?

Michael Storper, a professor at UCLA’s Luskin School of Public Affairs, asked himself the same question and, with the help of a research team, delved into both the data and the history. They learned that the regions were roughly equal in the early 1970s but soon began an immense divergence. They explain how it happened in a book, “The Rise and Fall of Urban Economies,” that was, ironically enough, issued in 2015 by Stanford University’s publishing arm.

Storper likens what happened in Los Angeles to the decline of the industrial upper Midwest. “Across these larger cities, Los Angeles most closely resembles Detroit,” he writes.

A big factor in the divergence, Storper and his colleagues found, is that the Bay Area developed collaborative organizations, such as the Bay Area Council, that have fostered technology’s expansion. Meanwhile, Southern California’s civic leaders ignored and neglected what had once been a strong technological base in the aerospace industry. They also struggled with the region’s immense diversity and the lack of cultural cohesion and regional identity that the Bay Area enjoys.

“In place of a new-economy agenda, (Los Angeles) regional leaders turned to developing low-wage sectors, such as light manufacturing,” while converting industrial land into housing, they wrote.

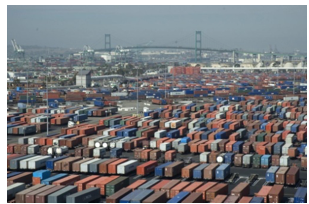

Initially, it seemed to be working out well for Los Angeles. By the mid-1980s, it had wrested away much of San Francisco’s once-dominant position as the state’s financial capital. It was also remaking its dilapidated downtown, expanding its international airport, staging a very successful Olympic Games and seeing overseas trade through its twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach expand dramatically as Asia’s economies surged.

However, a serious meltdown was just around the corner. The dramatic end of the Cold War in the early 1990s led to a near-collapse of the Southern California aerospace industry and made the region the center of a severe statewide recession. More than a million people, many of them aerospace workers and their families, decamped for other states, UCLA economists later calculated, while at least as many economic and political refugees from other countries, particularly Mexico, filled the population vacuum.

The exchange of population not only altered the ethnic/cultural tenor of the region but also fueled a labor union movement, particularly in Los Angeles County, that pushed politics leftward, tilting the entire state toward Democratic Party dominance.

Although port traffic surged, creating hundreds of thousands of longshoring, trucking and warehousing jobs, those could not fully offset the loss of high-skill, high-pay aerospace jobs. And most of the recent immigrants lacked the education and skills that a post-industrial “new economy” required.

While immigrants filled the service sector’s demand for low-pay labor, the region offered ever-fewer pathways into the middle class and found itself with a very large, at least semi-permanent underclass. One data point illustrates the contrast: College graduates are, as a percentage of population, 50 percent more numerous in San Francisco than in Los Angeles County.

Up north, meanwhile, technology, much of it generated in and around the Bay Area’s universities, and a torrent of venture capital were transforming what had been an agricultural area near San Jose into Silicon Valley, the throbbing heart of a new global economy based on the manipulation of electronic symbols.

Up north, meanwhile, technology, much of it generated in and around the Bay Area’s universities, and a torrent of venture capital were transforming what had been an agricultural area near San Jose into Silicon Valley, the throbbing heart of a new global economy based on the manipulation of electronic symbols.

New corporations were born with names like Apple, Facebook, Google and Intel. Hundreds of thousands of bright young men and women, including many from other countries, made the pilgrimage to the new economic Mecca.

Eventually, Silicon Valley expanded throughout the Bay Area, particularly into San Francisco itself. The money it generated fueled enormous booms in real estate and in catering to the newly affluent, from the restaurants of San Francisco to the vineyards of Napa and Sonoma counties.

The rest, as they say, is history. The Bay Area exploded while the Los Angeles area languished, and the result was the enormous economic gap now separating the two.

But what of the future?

While Storper, et al, compare Los Angeles to Detroit, there’s also another analogy. A century ago, Detroit was the Silicon Valley of its era, attracting enormous entrepreneurial talent and venture capital, and creating an entirely new industry — cars — that became global. But it took its dominance for granted, ignored its economic fundamentals and was devastated by leaner and meaner rivals.

The same fate could befall Silicon Valley if its traffic and housing problems continue to fester, encouraging the brains and the money to shift to more hospitable and lower-cost climes, particularly those in other states. Already, says Robert Kleinhenz of Beacon Economics, the Bay Area’s economic growth “is being constrained by a lack of affordable housing and a lack of skilled labor. These factors are having a disruptive effect on the job market.”

Meanwhile, Los Angeles is belatedly trying to immerse itself in the high-tech economy via a “Silicon Beach” in the Santa Monica area. But so far, it has not generated the start-up energy that fuels its more established rival to the north and mostly exists as an outpost of larger companies.

However, the aerospace industry, through such efforts as Elon Musk’s SpaceX, is showing signs of new life. And while the region’s iconic film and TV production industry is holding its own, it isn’t the major economic driver many presume it to be — about 7.5 percent of L.A. County’s private employment, by the most generous estimate, and far less than that in the region as a whole. Los Angeles also has become a magnet for investment capital from Asia, particularly in real estate.

The twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach continue to see growth in cargo, particularly in-bound shipments of goods from China. But last year, an enlarged Panama Canal opened that can handle much-larger “Panamax” ships. It encourages shippers serving markets in Eastern and Southern states to bypass California and the necessity of off-loading containers onto trains or trucks for shipment eastward.

The twin ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach continue to see growth in cargo, particularly in-bound shipments of goods from China. But last year, an enlarged Panama Canal opened that can handle much-larger “Panamax” ships. It encourages shippers serving markets in Eastern and Southern states to bypass California and the necessity of off-loading containers onto trains or trucks for shipment eastward.

It’s too early to tell whether the expanded Panama Canal route will seriously and adversely affect Southern California and the estimated one million regional jobs tied to international trade. But it’s something else for the region’s leaders to ponder as they try to improve its lagging economic condition. However, they can take some solace from a political shift. While the Bay Area was becoming more dominant economically, it was losing its decades-long dominance in Capitol politics that such legendary leaders as Willie Brown and John Burton personified.

Both houses of the Legislature are now led by Latino politicians from Los Angeles County, reflecting the Southland’s huge population advantage and the rising political clout of those immigrants who poured into the county as aerospace workers departed a quarter-century ago.

The 2018 contest for governor could become another venue for the political rivalry. Former San Francisco Mayor Gavin Newsom and former Los Angeles Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa are the leading contenders.

And, of course, there are the Dodgers, who this year, at least, are dominating the Giants.

(Dan Walters has been a journalist for nearly 57 years, spending all but a few of those years working for California newspapers. He has written more than 9,000 columns about California and its politics and his column has appeared in many publications, including The Sacramento Bee, The Wall Street Journal and the Christian Science Monitor. This Walters perspective originated at CalMatters [[calmatters.org]]] .. a nonpartisan, nonprofit journalism venture committed to explaining how California’s state Capitol works and why it matters.)

-cw