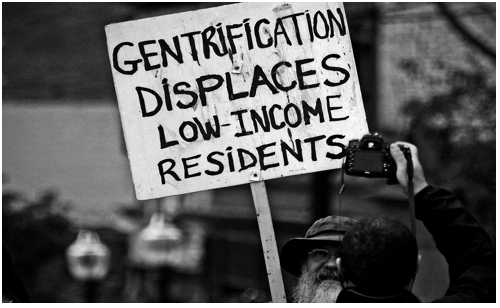

CommentsPLATKIN ON PLANNING--In an editorial critical of the pushback against gentrification in Boyle Heights, the Los Angeles Times portrays gentrification as a result of blind economic forces that also uplift local communities.

I challenge both of these claims. City Hall’s official ordinances and regulations, as well as many informal practices, not only allow gentrification, they actively promote it at the expense of local communities. Since gentrification takes many forms in Los Angeles, in both low income and middle-income areas, let us carefully examine several types to better understand the proactive role of local government in Los Angeles. (As an extra, I will also explain how the Federal Government partners with local government to promote gentrification.)

Mansionization: I happen to live in Beverly Grove, the Los Angeles epicenter of McMansions, as well as of apartment evictions and tenant buyouts. Over the past 12 years my middle class neighborhood has easily lost over 200 homes to the mansionizers, leading to the wide scale elimination of starter homes, sunlight, privacy, street parking, and boulevard trees. After the mansionizers quickly bulldozed these existing homes, they replaced them with pricey, boxy, shoddily built houses that filled all available lot space, and then some. These McMansions are generally three times as large and three times as expensive as the houses they replaced. The new occupants, who typically sell and move on after two years, are also far wealthier than the residents they displaced.

In over 12 years of campaigning against these mansionization trends, my neighbors and I have made many discoveries of official City Hall support for mansionization, as well as for evictions from nearby Beverly Grove apartments.

To begin, the McManions were legal because Los Angeles had one of the most permissive residential zoning codes of any American city. Later, when enormous community outrage forced City Hall’s hand, the City Council twice adopted phony “anti-mansionization” ordinances to chill us out. As we then predicted in public testimony, these two ordinances contained so many deliberate bonuses and exceptions that investors and contractors would rely on these loopholes to continue to build and flip the very same McMansions. Thanks to the City Council, they never missed a beat.

As our opposition grew, we soon discovered that the Department of Building and Safety (LADBS) hid the plans for these McMansions from public view. When we next began to monitor individual McMansions, we learned that LADBS rarely enforced City Council ordinances that required the advanced posting of demolition permits and current posting of building permits.

Shortly after this we also learned that the demolition of older homes releases two deadly toxins into the atmosphere: asbestos and lead paint. But, unlike other cities, Los Angeles ignores legal requirements to remediate these toxins before and during house demolitions. Instead, local residents must, case-by-case, contact the South Coast Air Quality Management District and LA County Public Health once a house demolition begins. In nearly every case nothing is left by the time a diligent but harried inspector manages to show up at a demolition site. As a result, the demolitions proceeded unhindered and exposed neighbors to dust from lead paint and asbestos. Not exactly the benefits of gentrification hailed by the LA Times.

To further complicate this picture, we uncovered many other irregularities and flat out code violations in the construction of McMansions, including buildings that were larger than approved plans and contractors who manipulated grade to gain several more feet of height. In the rare cases that we could actually get an LADBS inspector to make a site visit, they always told us that the McMansions in question were perfectly legal. One inspector even told me, like my neighbors, that I should stop opposing progress. In other cases, the LADBS inspectors told local residents to stop submitting code violations and, instead, plant bamboo to conceal McMansions they did not like.

Since then, after a decade of relentless campaigning, Beverly Grove finally obtained LA’s fourth Residential Floor Area district (RFA). We incorrectly assumed it would finally stop new demolitions and McMansions, but we were naïve. Crafty mansionizers submitted their building plans to Building and Safety before the RFA’s effective date. In LA, this allowed their future projects to become vested. In turns out that unlike other cities, Los Angeles does not require a building permit or initial construction for a project to become vested. Investors only need to submit plans and pay fees. What a deal!

After that, the vested project can linger for years until construction begins.

Furthermore, projects that superficially conform to the Beverly Grove RFA still continue with their other dirty tricks. Demolition permits and building permits are not posted. Actual construction sometimes conflicts with approved plans, resulting in houses that exceed the height and size provisions of the RFA. And, as before, LADBS always makes the same call. The new boxy houses are still perfectly legal.

So, don’t tell anyone in Beverly Grove, or countless other Los Angeles neighborhoods, that this form of gentrification only results from blind economic forces. Like apartment house evictions preceding new luxury units, we have seen, warts and all, how the City’s laws and enforcement practices result in the gentrification or our neighborhoods.

Other types of gentrification: Mansionization is only the tip of the iceberg because Ellis Act and informal evictions, Small Lot Subdivisions, and the wide-scale construction of luxury housing at the expense of local residents all rely on formal support from City Hall. These, too, are rampant in Beverly Grove and adjacent neighborhoods, and it is this construction that eventually leads to the same retail changes taking place in Boyle Heights.

Let us also take a quick look at several other ways in which City Hall systematically ushers in gentrification.

Re-code: LA will systematically change most of LA’s zoning laws, usually to loosen up local building restrictions. Originally billed as a simplification of the 1946 zoning code, in practice Re:code LA has enormously complicated the zoning code. This is because the City Council is systematically adopting its intricate zone changes before the completion of the General Plan’s updates. The cart is not only before the horse; it left the buggy behind.

Community Plan Updates, such as the current updates of the Hollywood and Boyle Heights plans, are little more than real estate plans. While they have page after page of wonderful policies and hypothetical City programs, their only actual implementation is appended up-zoning and up-planning ordinances. Everything else, especially infrastructure monitoring and funded infrastructure improvements, will be hidden away as a shelf document.

To illustrate the pro-gentrification natures of the updated Community Plans, these are the goals of the Boyle Heights Community Plan, which City Planning is now updating. I have boldfaced its heavily coded pro-gentrification goals below.

“Boyle Heights is currently one of the more urban and dense neighborhoods in the City, as well as one of the most transit accessible ones. As such, the update of the Plan aims to encourage specific growth around transit hubs and commercial corridors, while conserving existing varied densities of the residential neighborhoods as well as historic character.

The Boyle Heights Community Plan Update is an effort to update the existing Plan (last updated in 1998) to:

- Reflect preferred future growth patterns in the area,

- Encourage wise growth,

- Identify appropriate locations for new development,

- Address prevailing neighborhood and community issues,

- Protect residential neighborhoods from development that is out of character and scale.

In contrast to these goals, anti-gentrification goals would be based on accurate, not inflated population data, as well as a careful calculation of the population buildout levels of existing zoning. These findings would determine the number of people who could live in the residential units built by-right on all local commercial parcels, as well as the added 35 percent residential increment that could be constructed through SB1818, the Density Bonus Ordinance.

As a result of this methodology, the General Plan designations and zones of many Boyle Heights subareas would be kept intact or even downzoned. Furthermore, the plans would make all future up-zoning ordinances contingent on long-term on documented infrastructure and zoning capacity. In addition, the adopted plans would subject all claims about Transit Oriented District ridership to monitoring. City Hall would no longer accept developers’ claims as the unverified truth.

In addition, the focus of the Community Plan Updates, through their implementation programs, would be properly funded and carefully monitored investment in public infrastructure and service systems.

Transit Neighborhood Plans are proliferating on existing and proposed METRO transit lines and transit stations. Like Community Plan Updates, these are real estate growth plans masquerading as Transit Oriented Districts, or in METRO’s parlance, Transit Oriented Communities. City Planning’s approach is local ordinances to up-zone and up-plan privately owned parcels near transit stations, while forgoing any funded programs to enhance ridership, such as Kiss ‘n Ride, Park ‘n Ride, bicycle infrastructure, bus interfaces, or pedestrian sidewalk improvements.

Pay-to-Play is quasi-legal soft corruption based on a quid-pro-quo. According to the Los Angeles Times, real estate developers and their operatives, such as attorneys and expediters, make major contributions to politicians in exchange for favors. The politicians then bird dog developers’ applications for special spot-zoning entitlements that will make legalize their projects. As a result of this quid pro quo, these applications smoothly move through their discretionary approvals and appeals.

Lax or total absent code enforcement, including of code violations, is rampant in Los Angeles. Whether one takes the pulse of the wealthiest neighborhoods, such as Bel Air, where residents have long battled an illegal Mohamed Hadid mega-mansion, or the poorest neighborhoods, complaints about Building and Safety code enforcement abound.

U.S. State Department EB-5 visas allow foreign investors to contribute $500,000 to a real estate project or REIT (Real Estate Investment Trust) in exchange for a Green Card for themselves and their immediate family. Most of the applicants and those receiving these visas are from China, with the line of visa applicants is longer than the number of EB-5 visas. There is now ample documentation that most of this EB-5 money goes into high-end, gentrifying urban real estate projects, with LA now a major destination. According to the Pasadena Star News, which interviewed USC law professor Neils Frenzen, “They (EB-5 visa holders) are investing in multi-investor projects like some of the big buildings that are going up in downtown L.A.,” he said. “Those are basically EB-5 investment pools. They are coming from developers or whoever is behind the development of the projects.”

Long-term implications

So far City Hall has little reason to turn back from the laws and practices that promote gentrification. As a result, Angelinos will pay a serious price for their negligence because real estate speculation is sucking up all the oxygen at City Hall. There is little attention and public resources left for projects that would truly uplift local communities and benefit most people in Los Angeles, including subsidized affordable housing. The other obvious categories are extensive tree planting, mini-parks and playgrounds, climate change mitigation, pro-active code-enforcement, density restrictions in impacted neighborhoods, alternative transportation modes, careful General Plan monitoring, and extensive public investment in infrastructure and service systems.

Can we expect the Los Angeles Times’s editorial writers, along with academia’s and City Hall’s silver-tongued exponents of pro-gentrification ordinances and practices, to switch approaches. Will they finally become forceful advocates for implementing and funding these public improvements? Don’t bet the farm on it.

(Dick Platkin is a former LA City Planner who reports on local planning issues for CityWatch. Please send any comments or corrections to [email protected]. Selected previous columns are available.

-cw