Comments

iAUDIT! - In the late 1920’s, a new style of cartoon began appearing in US newspapers. The cartoons, drawn by Reuben (Rube) Goldberg, pictured wildly complicated and amateurish ways to perform simple tasks, like remotely rocking a baby’s crib. Over the next three decades, his name became so closely associated with making tasks unnecessarily complicated, it became a verb. To “Rube Goldberg” something means to find the least efficient, most complex way to do something, usually in a very ad-hoc and slapdash fashion. Although Goldberg died in 1970, there are still plenty of Rube Goldberg processes out there to carry on his legacy. The latest example may be LAHSA’s Point In Time (PIT) homelessness counts.

With all the news surrounding the ICE raid protests, the Isreal-Iran conflict, and the No Kings demonstrations, a very important piece of news may have slipped under most peoples’ radar. On Thursday June 12, LAIst published an exposé on how poorly LAHSA performs its annual Point In Time (PIT) counts. The PIT count’s purpose is to estimate the number and locations of unhoused people in Los Angeles County. The federal department of Housing and Urban Affairs (HUD) requires the count as a measure of homeless program performance. Although HUD publishes basic requirements for the survey, specific methods are left to each Continuum of Care (CoC) agency. The purpose of a CoC is to provide regional coordination of homelessness programs. In Los Angeles County, HUD’s designated CoC is LAHSA (except for Long Beach, Glendale, and Pasadena, which have their own CoC designations). Among other things, the count is used to allocate resources to LAHSA’s eight Service Planning Areas (SPA) spanning LA county. The count also has value as a public relations tool. When the 2024 count was released, Mayor Bass and former LAHSA CEO Dr. Va Lecia Adams Kellum lauded it for a small decrease in overall homelessness and an uptick in sheltered homelessness. In an unusual move. Dr. Adams Kellum released the 2025 count’s initial data in March, before it was subjected to data review. The 2025 count showed another drop in homelessness. Count results are usually released in late summer after a review by data analysts. Dr. Adams Kellum said she announced the count’s results early to counteract the negative news from two devastating audits of LAHSA, one from the LA County Auditor-Controller and one from an independent court-ordered review.

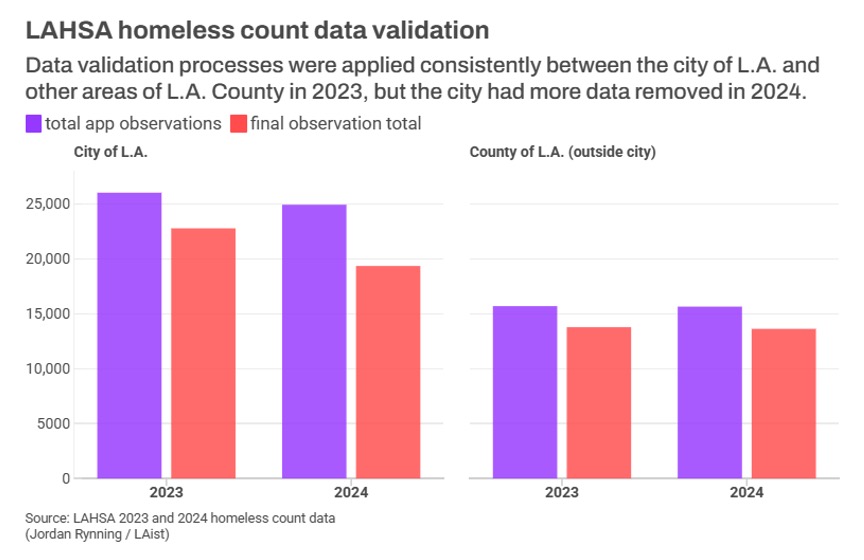

Although there have been many critical reports of LAHSA’s PIT count process in past years, the LAist article gives us a detailed account of the behind-the-scenes machinations that make the counts so questionable. According to the article, in 2024, hundreds, if not thousands, of unhoused people were missed in the count because LAHSA simply excluded them. Per the article, “LAist found nine areas — all inside Los Angeles city limits — where more than 100 observations of homelessness were removed from LAHSA’s preliminary totals of app and paper data by the time the count was finalized”. The text was accompanied by a chart showing the final count was reduced in 2023 and 2024 from initial counts reported by field volunteers.

The exclusions from the 2024 exceed the supposed reduction in homelessness, which was a quarter of one percent countywide and a little more than two percent in the City of LA. As I and others reported after the 2024 count was released, a professor from USC’s Suzanne Dworak-Peck School of Social Work (with which LAHSA contracts for data analysis) said the count’s margin of error was 1,592—or greater than the reported decrease; the real number of unhoused people could have actually increased. To quote the professor, the supposed decrease was “statistically insignificant”. Combining the margin of error with the reductions shown in LAist’s charts, you can see how the real number of people on the streets could easily have remained the same or increased. LAist’s reporters spoke with people directly impacted by homelessness, including the unhoused themselves, who haven’t seen any decreases, and in some areas said there have been significant observable increases in people on the street.

To illustrate the Rube Goldberg nature of how LAHSA handles the data, LAist also found the Authority has no written policy on reconciling questionable count numbers; managers make corrections on the fly and basically ignore any numbers that are too difficult to revise. While LAHSA management told reporters the count is "an estimate", in 2024 and 2025, Mayor Bass claimed a definitive and significant drop in homelessness, based on shoddy data collection and massaging the numbers. All of the inconsistencies create a surreal situation in which LAHSA’s managers try to downplay the count’s value, calling it an estimate and saying, “It’s important to note that Homeless Count data is just one measure of our system. Albeit an important one, it plays its own specific and limited role”. At the same time. Leaders like Mayor Bass and Dr. Adams Kellum (as well as the leaders of corporate nonprofits that financially benefit from maintaining the status quo) cite the numbers as empirical proof their programs are working.

As troubling as LAist’s report is, when considered in context of other news, its even more alarming. Put the LAist report together with allegations from whistleblowers that former LAHSA CEO Dr. Va Lecia Adams Kellum wanted the numbers changed so Bass' Inside Safe program wouldn't look bad and you see how the City and LAHSA leadership has been working together to spin the numbers to make them look much better than the reality on the street.

The allegations about Inside Safe tells us why it’s so important for leaders to manipulate the PIT count numbers. Depending on how one accounts for the expenditures, between $2 billion and $4 billion are spent on homelessness in LA every year. Measure A will add to the revenue stream. Much of that money goes to a group of politically connected corporate nonprofits, some of which have budgets equal to a medium-sized city. There is a huge financial and political stake in controlling the narrative around homelessness. For years, taxpayers have been told a few more million dollars or a new tax would solve homelessness once and for all. As homelessness increased, leaders became more desperate to show some kind of progress, especially in 2024, with Measure A on the November ballot. The PIT count, wrapped in arcane processes and obscured by managers who can make the count say what they want, is the perfect opportunity to show progress.

Consider the Mayor’s signature Inside Safe program. According to the City Controller’s dashboard, more than $450 million has been spent on Inside Safe, and 1,039 people have been housed, at a cost of about $433,000 per person housed. At the same time, 1,579 people--fifty percent more than were housed--fell back into homelessness. Spending nearly a half-billion dollars to house just over 1,000 people is neither a responsible use of public funds, nor does it do anything to substantially reduce homelessness. But Mayor Bass has cited Inside Safe as the primary driver of the supposed reduction in homelessness. Without the decrease in the PIT count--real or not--the mayor would be hard pressed to prove her unsustainably expensive program works. The whistleblower allegations suggest Adams Kellum, with whom Bass has been friends for years, manipulated Inside Safe numbers to make her friend’s flagship program look as successful as possible.

Inside Safe is just one example of the jigsaw puzzle of costly homelessness programs that have yet to show they’ve significantly decreased homelessness. Confronted with that fact, LAHSA’s managers resort to Rube Goldberg hacks to manipulate the numbers and call it “data cleaning”. LAist quoted a LAHSA manager as saying. “LAHSA employs the data reconciliation process to improve the accuracy of the Homeless Count, not to fulfill a narrative,” a statement so transparently self-serving, it would be funny if it didn’t support a system that condemns 75,000 people to life on the streets. LAist’s report gives us one more reason to call for foundational reform of Los Angeles’ homelessness programs.

(Tim Campbell is a resident of Westchester who spent a career in the public service and managed a municipal performance audit program. He focuses on outcomes instead of process in his iAUDIT! column for CityWatchLA.)