CommentsCAP & MAIN REPORT--For Sacramento, July is traditionally the calm before the storm — when state lawmakers and lobbyists desert the capital during the summer recess to brace for August’s legislative onslaught and its end-of-the-month deadline for bills headed to the governor’s desk. This year, however, the lights have remained on in both the offices of Governor Jerry Brown and the state’s powerful oil lobby.

Earlier this month, Brown and Western States Petroleum Association (WSPA) president Catherine Reheis-Boyd confirmed reports of ongoing direct talks between the governor and oil industry groups over what a Brown spokesperson told Capital & Main in a carefully worded email statement was an extension of “the state’s cap-and-trade program and climate goals beyond 2020.” The statement said talks were taking place for the sake of “market certainty” and to “ensure ongoing funding for clean energy programs, especially in vulnerable communities.”

A similarly vague message from Reheis-Boyd said only that the talks were aimed at “improving the state’s current programs and ensuring legislative oversight concerning the decisions that will determine California’s next course of action to combat climate change.” (Another oil group, the California Independent Oil Marketers Association, did not respond to a request for comment.)

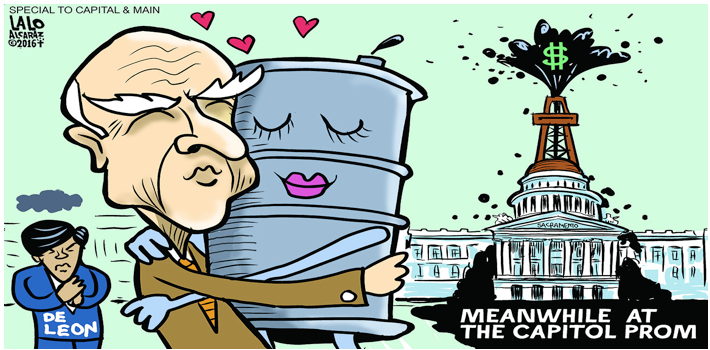

Though both sides declined to speak on the substance of the negotiations, the likely assumption is that the governor is seeking to cut a deal for Big Oil’s pledge to remain neutral on two of this year’s climate bills that are considered essential to the future of the state’s pioneering cap-and-trade program and long-term carbon-emission reduction targets.

Cap-and-trade is California’s approach to driving reductions in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. The “cap” sets a gradually lowered limit on emissions; the “trade” creates a market for carbon allowances, incentivizing polluters to innovate in order to meet their allocated limit. The less they emit, the less they pay. The money raised through the auction sale of carbon credits is earmarked for projects that help the climate and the environment in general.

Senate Bill 32 would extend and further raise California’s GHG reduction goals beyond 2020, the short-term target date set by 2006’s landmark Assembly Bill 32. Its companion bill, AB 197, which is still being refined, spells out the power of the Air Resources Board (ARB) to use market-based compliance mechanisms for reducing emissions from “stationary sources” and the transportation sector, while appeasing fossil fuel-friendly Democrats by requiring state officials to both prioritize and consider the cost effectiveness and technical feasibility of emission reduction efforts.

But the very fact that Brown is resorting to what amounts to domestic shuttle diplomacy across L Street is already a tacit admission that the influence wielded by Big Oil and its allies among the caucus of “moderate Democrats” amounts to a stone wall when it comes to taking decisive action on averting the catastrophic consequences of climate change and ensuring Brown’s climate legacy beyond 2018, when he will leave office.

“It’s no secret what the oil industry in California has been after for a long time,” said Natural Resources Defense Council attorney Alex Jackson, “and that’s to prevent California from showing an effective path forward on climate change that can serve as a model for others to emulate. They’ve invested in electoral politics and initiatives in the past that have now set them up with some leverage to try to thwart California’s next big steps after 2020, if their demands aren’t met.”

The oil industry spent a record $22 million lobbying California legislators and officials last year (as of May, the total for the 2015-16 legislative session had topped $25 million), with much of it directed at resisting the legislature’s efforts to turn the ambitious climate goals laid out in Brown’s 2015 State of the State address into law.

That muscle was dramatically flexed last September when the lower house’s mod Dems caucus, led by then-Fresno Assmbleymember Henry Perea, defied the governor and its own party leadership by successfully gutting SB 350 of its 50-percent-by-2030 gasoline reduction provision. Those cuts had been part of the effort authored by Senate President Pro Tem Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) to codify Brown’s ambitious goal of achieving an 80 percent emissions reduction below 1990 levels by 2050.

The mods also forced Senator Fran Pavley (D-Agoura Hills) to hold over to the current session its sister bill, SB 32, albeit pared back from its original goal of codifying Brown’s existing executive orders to reduce climate emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2030, and to 80 percent below 1990 levels by 2050. The version that will now need to get past the oil Democrats’ roadblock — and that must be passed in tandem with AB 197 to become law — contains only the 2030 target.

Part of what’s at stake for the governor is the legal cloud over whether, under AB 32, cap-and-trade requires legislative reauthorization beyond 2020. State Republican leaders insist that without reauthorization, it must end at that date; Brown and California’s Air Resources Board (ARB), which oversees the program, argue that AB 32’s language explicitly empowers the state to continue the program — and set new emission standards — without the legislature’s approval.

Those uncertainties have been complicated by an ongoing court challenge by WSPA’s business ally, the California Chamber of Commerce, that seeks to invalidate the entire cap-and-trade program on the grounds that the billions in auction proceeds constitute an illegal tax.

Last week, Brown and ARB released a plan to proceed with new emissions caps and future auctions and the allocation of allowances after 2020. However, concerns over the state’s long-term commitment to emissions reductions by the carbon marketplace are believed to have played a part in May’s disappointing auction of pollution credits.

Though the billions that have been generated in auction proceeds are a byproduct of the program — the focus of cap-and-trade is to lower caps on emissions — the revenues are considered essential for investing in clean-energy technologies and in the communities that have been most severely burdened by state climate policies.

“It is ultimately about putting a price on polluting,” said Susan Frank, director of the California Business Alliance for a Clean Economy. ”It’s about forcing emitters-slash-polluters to pay something so that over time that cost becomes too much for them. That in the end it becomes less expensive for them to be cleaner, to reduce their emissions, to innovate and invest and do better than it is to pay to pollute. We have to let this unfold. It is the uncertainty of the program that contributed to what happened in the May auction, and it may very well happen similarly with August and November. But ultimately, the business community that I represent needs the certainty of a post-2020 game plan.”

The surest way of achieving that certainty is for the governor and legislative leaders to immunize the state’s climate initiatives from further legal challenges by “bulletproofing” this year’s two-bill omnibus with the supermajorities mandated by the fiscal straightjacket of 2010’s Proposition 26, which defined fees as in the same revenue class as taxes.

But that means getting the oil industry to stomach California’s “clean-gasoline” mandate, AB 32’s Low-Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS), which gradually lowers the cap on the amount of carbon generated from “well to wheel.” It aims to rid at least 10 percent of the carbon from California’s transportation fuels by 2020, which are currently capped at two percent. It forces companies that produce “dirty” fuels to either meet carbon-reduction targets directly or purchase credits from clean-fuel producers.

LCFS is routinely hailed by environmentalists as a model of progressive and thorough fuel-regulation policy. It is also the feature of California’s regulatory landscape most feared and hated Big Oil. That’s because together with cap-and-trade, it strikes directly at gasoline and diesel profits by jumpstarting a market for alternative transportation fuels such as liquid biofuels, renewable natural gas, electricity or hydrogen. And the the world is watching.

“We have other states and regions that are looking to join up,” Susan Frank noted. “California’s ability to succeed with a market-based program has implications regionally and nationally and globally. And while it is only one program on a larger slate of policies, all eyes are on California to see if this effort is going to be successful. And it’s been successful.”

The oil industry has not been idle. It forcefully struck back with 2010’s failed Proposition 23, a ballot measure that sought to effectively suspend AB 32 altogether. Then, during in the months leading up to last year’s addition of transportation fuels to the cap-and-trade program, WSPA waged what’s been called a multistate, multi-million-dollar “AstroTurf campaign,” attacking LCFS not only in California, but also in Oregon and Washington State by claiming that the program would result in price spikes and fuel shortages. In fact, the standard resulted in a 36 percent increase in clean-fuel use in the state and $650 million invested in clean-fuel production.

And the industry hasn’t let up even in the midst of its negotiations with the governor. The messaging being broadcast in its most recent round of attacks on SB 32 and LCFS, through groups with grassroots-redolent names like Californians for Affordable and Reliable Energy (CARE) or Californians Against Higher Taxes, continues to cast doubts about the viability of cap-and-trade while portraying the state’s investments in clean energy as a waste of public money. Or, like the current “Fed Up at the Pump” sticker campaign by the California Independent Oil Marketers Association, it implies that LCFS and cap-and-trade constitute an illegal tax.

That kind of vehemence has raised speculation that the industry is less than sincere in its negotiations with the governor.

“I think that certainly it is possible that there is a larger strategy here to negotiate in bad faith,” Environmental Defense Fund director of Oil and Gas Program Tim O’Connor told Capital & Main. “The oil industry … has been in opposition to these policies for years and certainly as alternative fuels have taken stronger hold, as emission reductions in California have started to become more and more evident at the refining level, they are not becoming more friendly to these policies.”

But the window is closing on the available time during which climate scientists say nations can still act cost-effectively to keep global average temperature to “well below the 2°C above earth’s pre-industrial levels” agreed to in last year’s Paris climate accord.

“Sea levels are rising now, albeit slowly,” said J.R. DeShazo, director of the Luskin Center for Innovation at the University of California, Los Angeles. “Habitats are slowly changing. The urgency arises from the fact that early preventive action has a much, much larger impact than a comparable action [taken] in 25 or 50 years.”

It is estimated that for the Western United States alone, the price tag for disruptions in water supplies caused by global inaction could reach $270 billion by 2025 and balloon to nearly $2 trillion by the end of the century. Averting more floods, heat waves, droughts and rising sea levels requires good faith and bold leadership by all of California’s energy partners. It also means that any intentional delay for political advantage can only be seen as a kind of Strangelovean brinkmanship.

If the clock is running on the planet, in Sacramento, time is ironically on Big Oil’s side. Even should cap-and-trade persevere in the courts, the oil industry has much to gain by stalling on cap-and-trade until 2017. By then, the industry will have two more “failed” pollution credit auctions to bolster a narrative that the program is already dead. It’ll also have the opportunity of November’s statewide elections to increase the ranks and the power of the mod Dems caucus. And 12 more months of inaction will paradoxically only increase pressure on the governor and Democratic leaders to accept the kind of watered-down emissions standards that today are unthinkable.

“The tactic of delay is one that big polluters have used for decades,” said Tim O’Connor. “We think, as do many, many others, that 2016 is the year for California to move forward, to push ahead on long-term climate targets. … Governor Brown in his negotiations wants to see California step up and lead, and I just don’t know whether we’re going to see a unicorn appear this year. It’s likely and probable that there are going to be some actions that focus on a simple majority vote, which is much easier than negotiating with the oil industry.“

(Bill Raden is a freelance writer in Los Angeles. This report originated at Capital and Main.)

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

05

Thu, Mar