CommentsGELFAND’S WORLD--We've had television that celebrates old movies -- Turner Movie Classics comes to mind. We've had TV stations run marathons of a single series, the most notable of these being I Love Lucy. Recently, CBS has come out with a separate channel that does its own twist on television history. Decades is broadcast locally on subchannel 2.2. It runs what it calls binges on the weekends. That's where you can see two straight days of a single series such as The Fugitive or The Twilight Zone.

What's the point of visiting old TV shows when there is so much that is new? I can think of one serious reason, one semi-serious reason, and one excuse. In order, they are the history of culture and technology, entertainment, and reminiscence.

In recognizing and reviewing television as a medium worth taking seriously as part of our cultural history, it is worth thinking briefly about television's early days and its immediate precursor.

Television began as a commercial entertainment medium that wasn't taken particularly seriously as art or even as entertainment. In this, it has a direct parallel in film. Consider: At this stage of our history, we can recognize that Casablanca, Metropolis, and City Lights are major works of art. But at the beginning of the movie industry, films were little more than brief documents of real life, spliced together roughly with little instinct for story or plot. Television's early days were also pretty rough hewn. It took a while for filmmakers to develop both technology and craft, and out of that foundation they learned how to tell stories made of flickering pictures. Television producers had grown up on the movies so they knew story telling, but they didn't have the pictorial quality of 35 mm film to work with.

There is also the point that story telling has to be adapted to the medium. Reading fairy tales from a book is a lot different than watching a Disney animated cartoon of ostensibly the same story. What is important to realize is that the most memorable films, the ones we go back to see a second time, would not have happened without the existence of a commercial film industry which was churning out tens of thousands of films. Out of that mass of celluloid, there were thousands of mediocre efforts and a small percent that were masterpieces. There were also a lot of movies that don't rival Sophocles for depth and wisdom, but carry a solid entertainment punch. Not everything has to be high art, and most things cannot be great art, but decently made entertainment has a value of its own.

So too with television. Early television was limited by a narrow picture that, unlike film, was of limited resolution. Like early film, it lacked color. Given the technical hurdles, we nevertheless got quite a lot of programs that are remembered for their comedic or entertainment value.

I've been taking a look at some of the 1960s era programs on Decades. For some of these programs, its been to revisit shows that I saw the first time around. That's the reminiscense part. For the sake of the three reasons listed above, I'd like to say a little about three shows -- Rowan & Martin's Laugh In, the Phil Silvers Show, and Route 66.

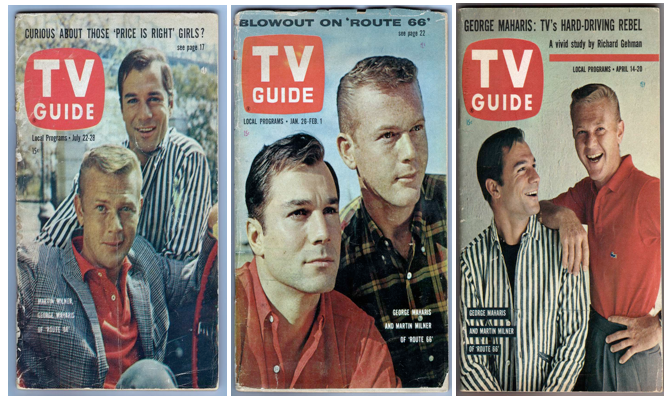

First to discuss -- and dispense with -- Phil Silvers and Route 66. I mention them because I saw them when they originally came out. One of them, the Phil Silvers Show, we watched as a family. It was the story of a conniving Sergeant in the U.S. Army who had a penchant for gambling and manipulating his commanding officer. I remember it as a high point of the week. At the time, the comedy clicked for me. I also saw a lot of Route 66, the story of a couple of otherwise normal seeming guys who drove from town to town in a fast corvette and found adventure wherever they went.

When I look at them now, they just don't seem to have the same oomph that they once had. I think that the reason is a combination of the technical and the cultural. The 1960 era black and white television image didn't have the capability of showing much detail. The rule of thumb for that technology was to put your subject close to the middle of the screen, big and contrasty. Directors didn't have the luxury of providing the viewers clues that were small or off to the side of the screen. In this sense, early television was very unfilm-like. The result is that these older shows delivered their plot twists with a lot of dialog because the ability to be visually subtle wasn't there. Because information was conveyed as much by words as by the picture, things got slowed down. Compared to the modern romantic adventure shows, Route 66 comes across as stodgy.

The Phil Silvers Show, remembered by many as Sergeant Bilko, is a little quicker, but its narrow screen format seems to render it a little claustrophobic by high definition television standards. To modern viewers, the Phil Silvers show looks like stage comedy done in front of the television camera.

What both Route 66 and the Phil Silvers Show have in common, compared to modern shows, is that the old television system was of inherently low definition. It was a fuzzy picture at best. For this reason, it could not show human expression as well as film. Let's try to explain this a little more precisely. Even in old films, it was possible to convey emotions such as suspicion or guilt with a glance or a subtle change of expression -- possibly a nod or a shifting of the eyes. Even the earliest 35 mm film was fully capable of showing these things. Early television wasn't. So instead of an actor warning his buddy that the robbers are in the next room by using a shift of the head, the old television action hero would have to convey the same idea with a shout and a lot of words: "Look out! They're behind the door!"

Modern viewers have become accustomed to receiving a lot of information visually. That's because the modern television screen has a wider format and lots higher resolution. In full color 1080i screen format, we have a picture that is beginning to rival that of celluloid. When television has moved on to the 4K format (even higher resolution), there won't be much difference between the movie experience and the television experience.

We've also become used to getting bits and pieces of the plot fed to us in quick cuts. Even if television stays within a single scene on a single set, there is camera movement and a lot of cutting back and forth between different camera angles. Often, one character's lines or actions are cut away from, leaving them to the imagination of the viewer. Modern viewers have been trained to put pieces together in their own heads, mentally inserting what has been left out.

Now for Laugh In. The show opened in 1968, a year in which street demonstrations against the Viet Nam War were on people's minds, even as the psychedelic scene brought in new art and music. Laugh In nibbles around the edges of the moment without really trying to confront political reality. That seems to have been the artistic price that had to be paid for being on network television at the time.

What Laugh In contributes to television culture is the jump cut. That's where the picture jumps from one scene to another without the blackout or slow dissolve that traditionally represents a movement in place or time. You might see Rowan talking to Martin and then instantaneously, the picture is replaced with another actor saying one word sarcastically, followed just as instantaneously by a jump back to Rowan and Martin. Jump cuts were nothing new to movie audiences, at least those who had seen Godard's Breathless in 1960. But Laugh In seems to be doing it just to have fun with itself.

In watching these old Laugh In reruns, you begin to figure out that the writers and video editors were making fun of all the old conventions of film and television. They also took pot shots at network censorship ("We can't say that on television"). In this sense, Laugh In is a part of our cultural history, and worth viewing in that sense.

There is one thing a little strange about Laugh In as viewed from our modern perspective. Laugh In put together a remarkable group of comedic actors, both male and female -- Henry Gibson and Arte Johnson on the one hand, and Goldie Hawn, Lily Tomlin, Ruth Buzzi, Judy Carne, and Jo Anne Worley on the other. In Laugh In, the women were generally the funnier and had to carry a lot of the comedic load, but they are also the ones who appeared in skimpy bikinis, sometimes with words written on their skin. Modern gender studies students would probably classify this as objectifying the women.

For example, Laugh In had a news segment (Rowan and Martin did the news portion) that was preceded by half a dozen of the women in ultra-short dresses or cheerleader costumes, singing and dancing the introduction.

There is another difference between Laugh In and modern TV variety shows. In the first season's shows that we've reviewed so far, the cast is almost entirely white. There are one or two exceptions, but nothing equivalent to a leading role.

One thing rather jumped out at me while viewing these old Laugh In reruns. From the news parody to the trashing of the accepted cliches of television drama, Laugh In is the precursor to Saturday Night Live. It's hard to watch the old reruns and not get that feeling in retrospect. It turns out that this wasn't either accident or piracy. Lorne Michaels, the godfather of Saturday Night Live, was a writer on Laugh In. Michaels has taken the original concepts further, but then he has had forty years of Saturday Night Live to do so. But the sarcastic approach to life and news started back in "beautiful downtown Burbank," as the Laugh In cast used to say. The writers also popularized "sock it to me" as a comedic expression, along with "you bet your bippy" and "verrry interesting."

At some point, historians will consider television to be a serious art form, just as they already consider it to be some of the best available data on cultural progression, fashions, and hard news. I can imagine future students of the 20th century checking out old collections of ER.

(Bob Gelfand writes on science, culture, and politics for CityWatch. He can be reached at [email protected])

-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

21

Sat, Feb