CommentsEDITOR’S PICK--Three weeks ago, I was traipsing through London’s Victoria and Albert Museum with a friend of mine who has the attention span of a hummingbird. One minute we were admiring the intense reds in Ottoman-era ceramic tiles from Turkey, the next we were surrounded by the ferocious beasts that had been woven 600 years ago into wool English hunting tapestries. By the time we stumbled on an ornately carved, stunningly out-of-place 16th-century oak staircase from Brittany, I felt not only jet-lagged, but completely lost. At that point, my friend gave me a compassionate, slightly condescending glance and reassured me that that’s what museums are for: getting lost.

She was right of course. Losing one’s self in the colors, textures, and stories of long-gone or faraway worlds is one of the principal joys of wandering through museums.

But I’ve recently also come to appreciate how much museums can give us a chance to go home. Since I was a child, I’ve enjoyed visiting Rembrandt’s tender portrait of his son, Titus, at my favorite museum in Los Angeles, the Norton Simon. Whenever I go to Madrid, I stop into the Prado to visit Velázquez’s slightly ridiculous depiction of Prince Balthasar Carlos riding an oddly plump horse. I learned to love the portraits of these boys when I myself was a boy, and over the years, each time I gaze upon them, I can recall the fascination I felt when we first met.

A few days ago in Chicago I got a chance to see an exhibition at the Art Institute that brought into focus the power of curating art around primary human themes. “Van Gogh’s Bedrooms” brought together approximately 36 of the Dutch artist’s drawings, illustrated letters, and paintings, culminating in the side-by-side presentation of the three versions he painted of his bedroom in Southern France. The crowds were large and poorly managed—to the point of tainting the experience. But the exhibition’s success suggests to me that museums could do a lot more to make art speak to people where they live, both literally and figuratively.

Too much of the way we talk about art flows from the pretentious modern cult of the artist as countercultural alchemist or seer. Modern art museums in particular often glorify the marginal—read detached and superior—status of artists in our society. The worst exhibitions can feel like elaborate inside jokes in which socially ambitious visitors try their damnedest to enter the ranks of the cognescenti. In other words, the purpose of their gaze is to boost them up the social ladder rather than to understand how the artists’ work or life might cast light on their own lives.

Van Gogh was one of the first artists to be romanticized way out of proportion, not only for supposedly sacrificing his life for his art but for exhibiting a sensitivity that the world could not or would not understand. Remember the lyrics of Don McLean’s hit single, “Vincent (Starry, Starry Night)”? “This world was never meant for one as beautiful as you.”

Oh please.

I just finished reading Steve Naifeh and Gregory White Smith’s biography of Van Gogh, and let me tell you, the poor Dutchman was no self-righteous bohemian who felt himself above social norms. He desperately longed for the things we all do: family, a sense of belonging, and a place he could call home.

Van Gogh himself was an avid reader of artists’ biographies. He wholeheartedly agreed with Emile Zola’s famous dictum that when looking at art, one must look for the artist behind it. In other words, you shouldn’t appreciate art for beauty or ideas alone, but for the way it helps you connect with the creator, whose pains and pleasures, insights and insecurities, might very well teach you something about your own.

Too much of the way we talk about art flows from the pretentious modern cult of the artist as countercultural alchemist or seer.

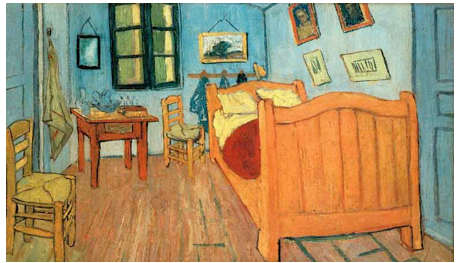

When Van Gogh painted “The Bedroom” in October 1888, he had just finished fixing up the one-half of a dilapidated yellow house he had rented in a seedy neighborhood in Arles. Paul Gauguin had just agreed to come live with him, and Van Gogh was anticipating the joys of having a home of his own where he could “live and breathe and think and paint.”

The painting was instantly one of his favorites. He felt it captured the feeling of “overall rest or sleep.” Simple, intense, and painted in saturated colors, “The Bedroom”’s oversized furniture, elongated floorboards, and walls that seem to lean inward gently pull the viewer forward. Van Gogh was proud of its ability to monumentalize something so ordinary.

The painting’s restful beauty stands on its own. But what the Art Institute’s “Van Gogh’s Bedrooms” exhibition does for the original painting as well as for the subsequent two—which were painted in an asylum after Vincent’s dream of a happy home had collapsed—is to contextualize them within the life of the artist.

The exhibition invites guests not merely to revere Van Gogh as a painter, but to empathize with him as a man whose desires and longings were not unlike our own. The entry hall to the exhibition details Van Gogh’s peripatetic life. In his 37 years on earth, he lived under 37 roofs across 24 cities. The first line of the first sign of the exhibition states simply that Van Gogh’s life “was marked by a persistent search for a home and a place of belonging.” The rest of the exhibition flows directly from that one sentence.

You wouldn’t know it from the lines outside the Art Institute of Chicago these days, but museum administrators across the Western World are scrambling to keep their institutions relevant in the face of rapidly changing demographics.

And yet for all the concern about the future viability of museums, few people are talking about the need for museum curators to change the way they frame and present exhibitions, to move beyond the insider art history mumbo jumbo curators use to narrate exhibitions. Labels emphasizing shifting techniques of craft, highfalutin intellectual concepts, or the minutiae of artistic movements seem to be written by Ph.D.s for Ph.D.s. The curators evidently assume that visitors should come to learn about art rather than to experience it.

But surely one can do both. To do that most effectively, it helps to frame and present works of art in terms that the broadest possible cross section of the public can understand.

It’s become a truism in the era of data overload that the curator is king. How we frame and present knowledge have become as important as the knowledge itself. Swiss-born curator Hans Ulrich Obrist has written that curating at its most basic should be about making connections between cultures and humans. You might describe it, he explains, “as a form of mapmaking that opens new routes through a city, a people or a world.”

Those routes should be drawn to arrive where people live, to appeal to their most fundamental memories, hopes, fears, and desires. Because neither the cult of the artist nor an undue focus on style or technique come close to shedding light on what it means to be human. And this, it seems to me, is the truest purpose of art.

(Gregory Rodriguez is the founder and publisher of excellent Zócalo Public Square … where this perspective originated.)

-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

14

Sat, Mar