Comments

CONSERVATION - A fact that has stuck with me from the research for the Los Angeles County Breeding Bird Atlas in the 1990s is that there was not a single neighborhood in the county that did not have at least ten breeding bird species. Residents can enjoy birds wherever they live. But beyond that minimum, the number of birds that are found in developed neighborhoods across the region depends on the number of trees, their size, species, and diversity, and associated landscaping. Most of Los Angeles Audubon Society’s territory is developed, so the urban forest is critically important to the diversity and number of birds to be seen and enjoyed by our members. This article discusses the attributes of urban trees necessary to support birds, some of the conservation work that we have done to protect trees for birds in the City of Los Angeles, and reflects on the changes in approach needed to create a more biodiverse urban forest.

What do our native birds need in terms of trees in our developed neighborhoods? They need places to forage. Cal State LA Professor and LA Audubon Board Member Eric Wood and his student Sevan Esaian researched what trees wintering and resident birds used in residential neighborhoods (link). The trees that had the most value to wintering birds were two natives, Coast Live Oak and California Sycamore, along with some nonnatives, Chinese Elm, Carrotwood, Southern Live Oak, Mexican Fan Palm, and Holly Oak. Of these, the native trees were far better for wintering birds. For resident birds, American Sweetgum (also known as Liquidambar) and Ash species were also used disproportionately to their prevalence. This research suggests some general rules: native trees are superior for birds: if not using locally native species, California natives are good, then North American natives (e.g., Southern Live Oak), and then selected global trees, mostly from the northern hemisphere and related to trees native to North America and California (e.g., oaks, ash, elms).

Resident and migratory birds in neighborhoods need space. The greater the volume (width and height) of tree canopy, the better. Professor Wood’s research shows this as well, and that the amount of tree cover correlates with neighborhood income. This is a common theme in urban forestry research, where it is well known that “trees grow on money” (link). State and local initiatives are designed to remedy this discrepancy, although focused primarily on the benefits of trees in terms of shade, with any bird habitat a side benefit if done well.

Shifting attention from street trees, which are often the focus of planting efforts, to private properties, research also shows that landscapes with more cover of native plants support greater numbers of birds, and particularly important plants are native oaks, Toyon, manzanitas, and sages (link).

A connected landscape is also a benefit for resident birds. Older research from the Mediterranean region shows that the urban forest, in forms as simple as a tree-lined street, helps to connect habitats for birds across the landscape (link), so the maximum number of resident bird species will be found if the urban tree canopy (or other shrub habitats) is more continuous. Migratory birds, in contrast, are quite good at finding habitat patches wherever they occur. Anyone who has reviewed the impressive bird list for Esperanza Elementary School near MacArthur Park can see this to be true. Migrants will find and use trees and shrubs in the densest of neighborhoods (if we protect and restore those habitats!).

Los Angeles Audubon Society regularly advocates on behalf of the urban forest as bird habitat and for its many benefits. As individual issues arise, we often provide formal comments to jurisdictions.

As an example, in 2019 the City of Los Angeles proposed to remove 15,000 trees as part of its Sidewalk Repair Program. In the Environmental Impact Report (EIR) for the project the City argued that this would not be a significant impact because they calculated that even though canopy would decline initially, by the end of the 30-year project period it would recover to what it was at the outset. LA Audubon submitted a detailed comment letter in 2020, which emphasized two key points:

- The City was proposing to remove tree species that were used more by birds and replace them with species used less by birds, which would result in significant impacts; and

- The City was proposing to replace trees that were taller and had larger canopy coverage with trees that would be shorter with smaller canopy coverage, thereby downsizing the urban forest significantly, which would also result in significant impacts.

We wrote in the letter:

Our Conservation Committee reviewed the tree removal and replacement notices from the Bureau of Street Services and compiled those related to sidewalk repair from September 2017 to April 2020. We categorized them by species and by tree stature (small, <30 ft, medium, 30–70 ft, large, >70 ft). Of the 301 tree removals and 272 tree replacements, there was a loss of 101 large-stature trees (127 large tree removals, 26 large tree replacements), an increase of 98 small-stature trees (8 small tree removals, 106 small tree replacements), and a loss of 33 medium-stature trees (166 medium tree removals, 133 medium replacement trees). These trends show that the City is installing shorter trees as part of the [Sidewalk Replacement Program] and consequently the volume of habitat, biomass, and environmental benefits of these trees will be lower even at the same canopy cover. It is not possible to make up for the loss of height, form, and leaf density of large trees like American Sweetgum by replacing them with small-stature trees such as Crape Myrtle. Even if the canopy cover were replaced, the total benefits to wildlife would be reduced.

The City approved the EIR anyway and two tree advocacy organizations sued to have the EIR set aside. As has been reported in the media, the case was recently decided and the judge ruled that the City had erred, based in large part on the arguments and evidence that LA Audubon had put forth in the record.

Even though there was a victory in that case, the City of Los Angeles has a replanting palette that removes natives, does not take birds into consideration, and dramatically downsizes the urban forest. The Los Angeles region has a long way to go if it is to maintain, let alone increase, the tree canopy within neighborhoods.

Two problematic trends in urban forestry are working against us. Urban foresters are recommending smaller and smaller trees to avoid future perceived potential conflicts with infrastructure and to reduce the costs of maintenance such as pruning and watering. Give any tree long enough and it will need to be managed; avoiding large trees is not going to be the maintenance-free future they imagine. Urban foresters also often promote trees from all over the world to increase the number of different species planted in a city on the belief this will protect against disease or a pest knocking out a lot of trees at once. Although this technically increases the number of species, it is terrible for birds, butterflies, and native insects that are part of a healthy ecosystem.

It will take more than simply changing planting requirements to increase tree cover and bird habitat. Focus needs to be on more than tree planting, which is the feel-good, easy part. We need to design and redesign public spaces and infrastructure so that they provide good growing conditions for trees, rather than accepting poor conditions of tiny tree wells and compacted soils and only planting trees that will tolerate them. That means developing mechanisms to ensure that trees are watered as needed, even during drought conditions. The water investment is worth it. Tree roots also need oxygen, so providing a large enough volume of uncompacted soil is essential. It is insufficient to dig a hole and hope for the best, especially for street trees, because the soil under roads and sidewalks is intentionally compacted and therefore can be impenetrable to tree roots. We need bigger tree wells, which means retrofitting existing sidewalks for this reason wherever it is possible. It could also mean using engineering approaches to extend tree root zones under pavement whenever hardscape work is done. This can be accomplished by using what are called “structural soils,” which have sufficient supporting structure to allow pavement on top of them but maintain spaces within the soil to allow roots to grow. Durable resin systems known as “silva cells” can accomplish this as well, providing large areas for root growth even with sidewalks or heavily used plazas above.

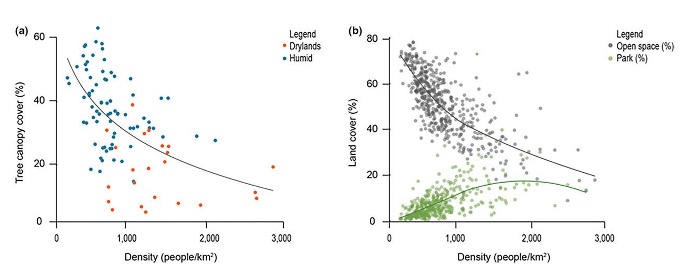

The future of the urban forest cannot be considered separately from the rampant construction and redevelopment in existing neighborhoods in Los Angeles. My colleagues and I have shown that the urban forest in Los Angeles County is being rapidly depleted in lower density residential areas as owners cut down trees to add building area and hardscape (link). This takes the form of mansionization, construction of accessory dwelling units, and even paving front yards for parking to accommodate the additional residents. Research on urban areas around the world shows that tree canopy and open space decline with increased residential population density (link). Housing density advocates point to some cities with high density and relatively high tree cover as examples of how density and environmental quality do not have to be contradictory. But this decoupling of housing density and tree cover is not what is happening in Los Angeles and the Los Angeles region is already the densest urbanized area in the nation.

Effects of population density on tree canopy cover in the 100 largest urbanized areas in the United States (a) and on the amount of open space and park space (b). Reprinted from McDonald et al. (2023) under a Creative Commons license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

The design and construction of human-scale, high-density housing with substantial associated greenspace is nowhere to be found in any of the current efforts to construct more housing in Los Angeles. That kind of transformation would take the purchase and massing of many lots to be able to spare larger areas from development and use them for trees and bird-friendly landscaping. What we have currently is simply the upzoning of small lots without taking care to ensure that there is any space left for trees and other vegetation, and the landscape and our urban nature is paying the price. In the City of Los Angeles specifically, officials are proposing to take affordable mid-density courtyard apartment neighborhoods and convert them into lot line to lot line apartment blocks. In other places they are proposing to upzone whole lower density neighborhoods with no means, or even idea of how, to protect or increase greenspace and habitat. No thought is being given to the livability of the future city and the open space element of the General Plan has not been updated since being written in 1973.

Los Angeles Audubon Society focuses on these issues because even though many people travel from their residence to watch birds, the most contact we have with birds is where we live. The pleasure and enrichment that birds can bring to everyday life should not be an afterthought (at best) in urban planning. Having the political fortitude to protect and enhance urban nature is not easy, but it is our aspiration to push elected officials in this direction, for the benefit of everyone and for the birds.

This essay was reprinted from The Western Tanager 89(4):1-3.

(Dr. Travis Longcore is an urban ecologist and the President of Los Angeles Audubon Society. )