CommentsCLIMATE POLITICS - Like its global predecessors, the COP26 Glasgow conference will usher in a new wave of apocalyptic warnings about climate change.

It will also likely prove no more successful, in terms of actually addressing the issue, than its predecessors, particularly as China, India and other developing countries ramp up their emissions.

Nevertheless, none of this will force the climate activists to reconsider how the current strategies against global warming could break the backs of the already beleaguered working and middle class. (For British readers, I use the phrase ‘middle class’ here in the American – less bourgeois – sense.) The climate chorus of celebrities, oligarchs and royals may feel virtuous, but for most people the future could prove to be propertyless proletarianisation. Many of those in Glasgow at the moment pray at the altar of ‘de-growth’. They want to limit the consumption of the working and middle classes, undermine their jobs, raise their energy bills, and inhibit their ability to buy property or travel.

These policies are fine with ‘woke’ corporatists like BlackRock, who see enormous profits in the regulated shift in energy, even as they seek to expand their business with the world’s dominant polluter, China. What’s missing is any focus on how to cut emissions without causing high inflation, raising energy prices and destroying the middle class. So far, more palatable options, like increasing remote work, geothermal energy, natural gas, nuclear power and varied new technologies, have not managed to get on to the agenda.

With climate, as with many other issues, the upper classes are inflicting their own preferences on working- and middle-class people. As nonprofits, oligarchs and bureaucrats plot out the future, small business owners and the middle class, as one entrepreneur put it, are ‘not at the table – or even in the room’. This is the very class – what I refer to as the yeomanry – that has driven much of the West’s economic progress and nurtured self-government. Democracy was born when both Athens and later Rome included small property owners in governance. Democracy died when these small owners lost power to what Aristotle labelled the ‘oligarchia’.

After the autocratic Middle Ages, both human progress and self-rule came back as the middle classes began to rise – first in Italy but then more profoundly, and more pervasively, in the Netherlands and the British Isles, before spreading to North America and Oceania, where there was no true hereditary aristocracy. Students of classical experience, such as Thomas Jefferson, James Madison and John Adams, all considered the over-concentration of property in a few hands as a basic threat to republican institutions, an insight shared by such intellects as Edmund Burke, Alexis de Tocqueville and Adam Smith (1).

After the brutalities of the early Industrial Revolution, and two world wars, the middle class thrived not just in America, but also in Britain, Australia, Canada and increasingly in East Asia. But by the 1970s we began what has become an inexorable march towards an ever more feudalistic structure. The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development has noted that, across the 36 wealthier countries, the uber-wealthy have taken an ever greater share of national GDP in recent decades, while the middle class ‘looks increasingly like a boat in rocky waters’.

These patterns are clearly evident in the United States, where wealth gainshave been especially concentrated among the top 0.1 per cent. The share of national wealth held by those below the top 10 per cent has fallen since the 1980s by 12 percentage points, the same proportion that the top 0.1 per centhave gained. Today, roughly half of all Americans earn less than $35,000 annually, living essentially pay cheque to pay cheque.

Even with their robust social-welfare provisions, over two thirds of European Union countries, including Sweden, have experienced declining social mobility. Germany is significantly less equal than its EU peers, with richer households controlling a bigger share of assets than in most other Western European states. The bottom 40 per cent of German adults hold almost no assets at all; barely 45 per cent of Germans own homes. Even in theoretically socialist China the top one per cent of the population hold about one third of the country’s wealth. Meanwhile, the prospects for the Chinese middle class are fading, particularly in light of the recent debt and housing crisis.

This lopsided distribution of income parallels a growing concentration of corporate power. Both in the US and Europe this has now seeped into the once dynamic tech economy. In Silicon Valley, the renowned garage culture has morphed into a collection of giant firms with market power unprecedented in modern times, controlling in some cases 80 to 90 per cent of their markets. ‘Free entry’ into tech and other markets is increasingly difficult without access to enormous financial resources.

As executive pay at the big tech and finance firms has hit the stratosphere, small businesses – the bulwark of the yeoman class – face ‘an existential threat’, according to the Harvard Business Review. Experts are warning that one third of small businesses could shut down for good. Hundreds of thousands have already disappeared, including nearly half of all black-owned businesses. Overall, according to a report from May this year, roughly 37 per cent of all US small business owners can’t pay their rent.

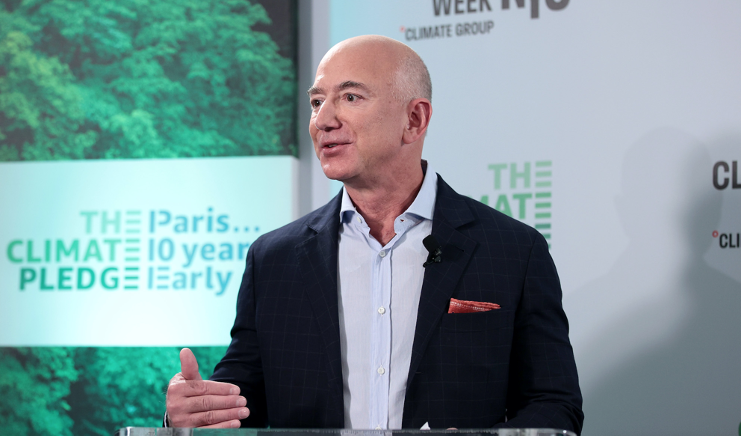

Loose monetary policy imposed during the pandemic has allowed larger firms to increase their share of the pie. Since the 2008 financial crisis, financial assets have consolidated and small banks, often critical for lending to small businesses, have been acquired or simply driven out of business. The Covid lockdowns also played a role in accelerating the continued shift towards large chains and online platforms like Amazon (which now uses its power to coerce small businesses to give up their data).

The lockdowns may seem tragic to operators on Main Street, but some greens see them as providing the basis for a bureaucratically controlled future where credentialed mandarins determine the minutiae of daily life. This includes policies designed to change how people live. Already climate-oriented policies have underpinned efforts to block affordable homes being built on the periphery and force ever more density on urban areas. This has had the effect of raising prices, resulting in declines in homeownership, particularly among the young, notably in the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada and Australia.

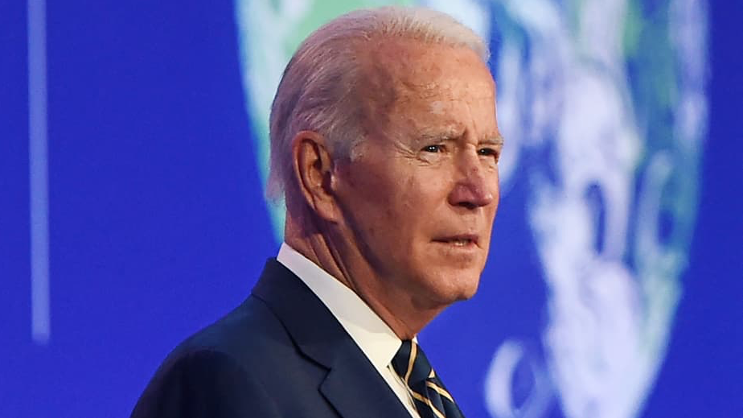

In the UK, the government’s Climate Change Committee is putting forward proposals that would make it impossible to sell single-family homes – including those built mere decades ago – that do not meet stringent energy standards. Such a regulation could escalate an already massive affordability problem. Similarly, California progressives, some developers and their media boosters seek a world in which single-family owners morph into permanent apartment renters. President Biden’s administration seems to be determined to push this across the US.

As in the Middle Ages, property is becoming ever more concentrated. Property ownership in Europe rests increasingly in fewer hands. In Britain, where land prices have risen dramatically over the past decade, less than one per cent of the population owns half of all the land. Even in the United States, a country that never experienced feudalism, property ownership now increasingly depends on inheritance. The offspring of property-owning parents are far better situated to own a house eventually (often with parental help) and enter what one writer calls ‘the funnel of privilege’. In America, those in Generation Z are three times as likely as Boomers to count on inheritance for their retirement. Among the youngest cohort, those aged 18-22, over 60 per cent see inheritance as their primary source of sustenance as they age.

This feudalisation of ownership may soon get worse. Enjoying record profits, some large banks like Britain’s Lloyds bank are working to gobble up an emerging market in distressed properties, apartments and even single-family homes. This trend is already pronounced and growing in the US, led by firms like BlackRock. In the first quarter of 2021, investors accounted for roughly one out of every seven homes bought, a marked increase from previous years. Analysts predict that soon most middle-class people will be ‘priced out’ of ownership in a ‘rentership society’, where homes, furniture and other necessities are turned into rental products offering endless cashflow to the oligarchs.

All this fits what the Davos crowd calls the ‘great reset’, a top-down effort at refashioning capitalism and daily life along green lines. The goal is not just to turn potential owners into tenants but also to reduce all consumption in general, as part of a move to a ‘net zero’ future where cars will become rarer, miles will be taxed and only expensive electric cars will remain, largely only for the rich.

The anti-middle class jihad also threatens the livelihoods of millions of working-class people, particularly those in well-paying manufacturing, construction and energy jobs. Green policies have already accelerated the de-industrialisation of countries such as the United Kingdom, and could undermine recent efforts to bring factories back from China. Those much heralded ‘green jobs’, so central to the climatista pitch, turn out to pay far less and are far less likely to be unionised. Many of them may end up in developing countries anyway.

Meanwhile, the likes of Jeff Bezos – who earlier this year gave $10 billion to environmental groups – continue to live in Nero-like luxury, flying in private jets and spewing many times more greenhouse gases than the ordinary mortal. It’s no surprise that US climate tsar John Kerry – another frequent flyer on private jets – believes his proposals are not a ‘sacrifice’ but ‘an opportunity’. He will no doubt be joined by Amazon, other tech firms and Wall Street in investing in renewable schemes, often subsidised by governments. Such firms are primed to be major beneficiaries of new green-infrastructure spending.

All this threatens to force much of the yeomanry towards a serf-like status. Many, particularly the propertyless young, will join a swelling proletariat dependent on government transfers and working limited hours if indeed they work at all. The scolds arriving in Scotland may claim to be saving humanity, but it’s the middle and working classes who are designated to pay the price.

The only way we can change this situation is for ordinary people to challenge elite policies – as has already happened, albeit chaotically, in France and several other countries. Even as we confront climate challenges, we must not allow green politics to become yet another nail in the coffin of the once great yeomanry.

(Joel Kotkin is the Executive Editor of New Geography and the author of The Coming of Neo-Feudalism: A Warning to the Global Middle Class. He is the Roger Hobbs Presidential Fellow in Urban Futures at Chapman University and Executive Director for Urban Reform Institute. Learn more at joelkotkin.com and follow him on Twitter @joelkotkin.)