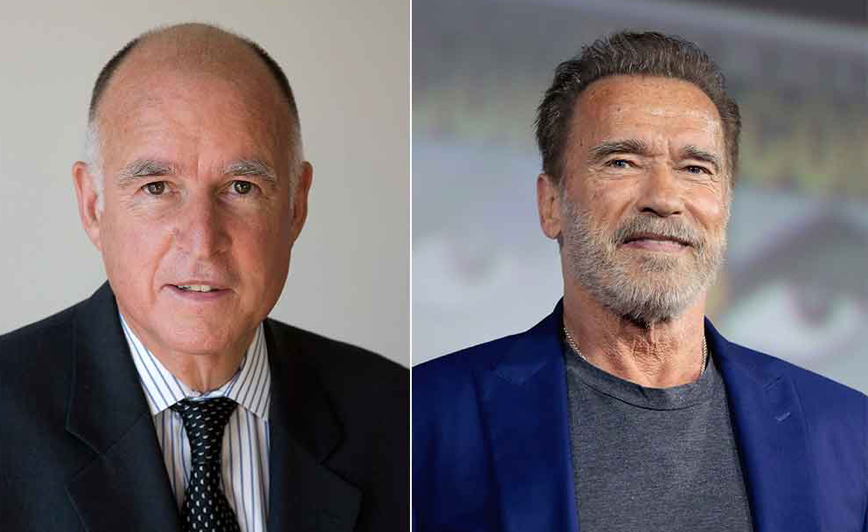

CommentsRUSSIA / UKRAINE WAR - I must be getting old. Jerry Brown is starting to make sense to me. Arnold Schwarzenegger is sounding like an international statesman.

And heeding the advice of former California governors now seems like the best path for humanity.

It’s improbable that these two ex-governors—one known for head-scratching aphorisms, the other for silly one-liners—are now global voices of reason and champions of peace. It’s also logical, in a perverse kind of way. As the world goes mad and sets itself on fire, where better to turn for wisdom and experience than crazy and combustible California?

Brown’s and Schwarzenegger’s ascents to sage status reflect the extent to which California, the world’s fifth largest economy, functions as its own country, with its governor serving as a second American president. California governors now sign international treaties, contribute to global climate policy, and constitute a fourth branch of the U.S. government—employing regulations, litigation, and our markets to check the president, Congress, and the courts.

When California governors leave office, they maintain high profiles but carry less political baggage than presidents, whose foibles our polarized and partisan media cover obsessively. The world and the U.S. lack statesmen, and Brown and Schwarzenegger have used their position and notoriety to fill the diplomatic void.

They’re doing so in a very California way, combining big visions and hard realism in statements with global reach. At a time of war, they mix nostalgic appeals to their own personal histories with dreams of a more peaceful future. But they do this with a blunt style that challenges the knee-jerk good-and-evil moralism that plagues America’s national politics. They argue for making common cause with rivals and enemies—the sort of hard-headed inclusion that represents the California idea at its best.

Schwarzenegger’s most recent message was for Russia in a short video he posted online that went viral in a matter of minutes. In the clip, Schwarzenegger pointedly told President Putin, whose Twitter account follows Schwarzenegger’s, to stop the war in Ukraine.

But the former governor also rejected the increasingly commonplace American condemnation of all things Russian. Instead, his message also embraced the country and its people. He employed his incredibly rich and varied life story—Arnold may have met more people than anyone alive, with the possible exception of the Dalai Lama—to talk about his visits to the country and relationships with friends there.

That approach, along with Russian subtitles and distribution over Telegram, the messaging app popular with Russians, gave Schwarzenegger an opening to try to penetrate misinformation and propaganda. He spoke bluntly about what is actually happening in Ukraine, directly addressing Russian soldiers there and noting that they themselves were victims of their government’s lies. The video’s most powerful, heartbreaking moment came when Schwarzenegger spoke to those soldiers about a subject he used to avoid: the war history of his father, an Austrian policeman who fought with the Nazis during World War II.

“The Russian government has lied not only to its citizens but to its soldiers,” he said. “When my father arrived in Leningrad, he was all pumped up on the lies of his government. When he left Leningrad, he was broken—physically and mentally. He lived the rest of his life in pain—pain from a broken back, pain from the shrapnel that always reminded him of those terrible years and pain from the guilt that he felt.

“To the Russian soldiers listening to this broadcast: You already know much of the truth that I’m speaking. You’ve seen it in your own eyes. I don’t want you to be broken like my father.”

As Schwarzenegger tugs at the heart, Brown—concerned about growing conflict between China and the West—hammers on heads.

In a remarkable essay published this month in The New York Review of Books, Brown took dead aim at calls in the American government—from both parties—promoting greater conflict with China.

He did so by framing the last 20 years as a period of war and human suffering, triggered by American actions after 9/11. America’s actions abroad, he wrote, “have killed more than 900,000 people, displaced at least 38 million, and cost the United States an estimated $8 trillion.” The country could have spent those dollars, he noted, on education, research, infrastructure, and other services.

But do our country and leadership even realize what we have done? “One might assume that such disastrous results, and the ignominious end of the war in Afghanistan last year, would lead to a period of reflection and soul-searching,” Brown wrote. “Yet no such inquiry has occurred—at least not one that fully grapples with the shocking self-deception, pervasive misreading of events, and powerful groupthink that drove the longest war in American history.”

Brown points to books and articles by “think tank specialists and defense department insiders,” like The Strategy of Denial by Elbridge Colby, for continuing to promote that groupthink. These policymakers now advocate provocative actions that increase the chances of a catastrophic war. These include more military competition, “selective nuclear proliferation” (in Colby’s formulation) to friendly countries, and alliances that might turn a Chinese invasion of Taiwan into a wider conflict with Japan, Australia, South Korea, and the Philippines.

The ex-governor, who leads the California-China Climate Institute, a think tank at UC Berkeley, is clear-eyed about the Chinese government’s dangerous and provocative behavior, from its treatment of Uyghurs to its repression of Chinese immigrants overseas. But Brown argues powerfully that war and conflict will only make things worse.

“Framing the China threat as irredeemably antagonistic, as many ‘political realists’ are currently doing, misses the reality that both countries—to prosper and even to survive—must cooperate as well as compete,” he wrote. In the piece, and in a recent interview with Politico, he warned against a “Manichean mood” in America, “a philosophy of ‘The world is sharply divided between good and bad, and we’re good, and they’re bad.’”

Brown argued instead for vigorous U.S. engagement with China, with a focus on avoiding catastrophes. He calls this strategy “planetary realism.” It is “an informed realism that faces up to the unprecedented global dangers caused by carbon emissions, nuclear weapons, viruses, and new disruptive technologies, all of which cannot be addressed by one country alone.”

That’s a powerful and convincing argument. And it should carry extra weight coming from someone who spent four terms governing California, a state that produces more than its share of disasters and catastrophes.

The world needs Brown and Schwarzenegger to keep counseling all of us. It’s a role that ex-presidents used to fill. But that was before Bill Clinton got effectively sidelined by his foundation’s lack of transparency, before George W. Bush became a painter, before Barack Obama went on a weird narcissistic bender with Bruce Springsteen, and before Donald Trump attempted a coup.

So, maybe it’s time for our last two governors to team up. They complement each other, the Philosopher-Nerd and the Muscleman-Movie Star. And their logos, pathos, and wise interventions might just save the world from itself.

(Joe Mathews rites the Connecting California column for Zócalo Public Square.)