Comments

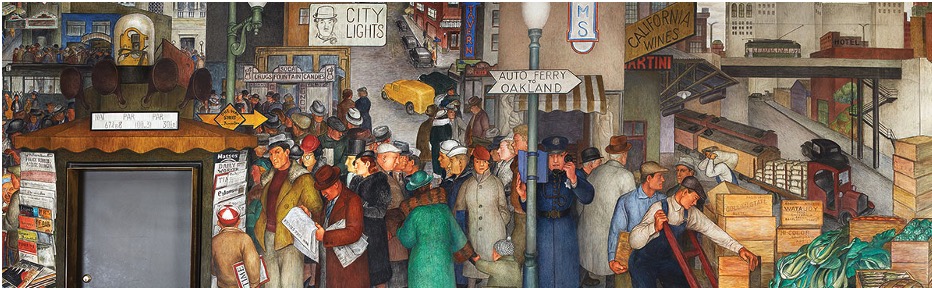

iAUDIT! - If you have never visited San Francisco’s Coit Tower, I encourage you to if and when you find yourself in The City. Besides being an architectural marvel, its interior houses a remarkable collection of murals depicting life in Depression-era California. As part of the New Deal’s Public Works of Art Project, 26 local artists created vivid visual narratives of commercial, agricultural, political, and social life in and around San Francisco. Although each is stylistically distinct, the murals share the neo-realist style of 1930’s United States: vivid colors with strong shadows expressing pressing social themes. The murals present a realistic, albeit stylized, view of a world mired in the depths of the Depression. An idealized San Francisco street scene includes a businessperson being robbed at gunpoint while others nonchalantly walk by. A wealthy family driven in their chauffeured car to view a new WPA dam gawk at a hungry migrant family camped by a stream. Workers march toward the viewer from a burning wheat field, some with clenched fists held high in the universal sign of socialism.

Besides their dramatic depiction of political and social upheaval, the murals are noteworthy for the context in which they were created. 1930’s San Francisco was far from the caricature of liberalism it now represents. It was city very much controlled by big business: the headquarters of banks, the Southern Pacific railroad, and powerful shipping companies crowded the financial district. While artists were working on the murals, a waterfront general strike resulted in two union members being shot to death by police. City leaders had artists redo some particularly controversial images, and delayed Coit Tower’s opening by several months to allow passions to cool. The other remarkable thing is that the murals were created by artists working for the US government (at the princely sum of $31 per month). Even after being revised, most of the murals unabashedly confronted the social inequities of the day. The murals’ raw imagery conveys themes that still resonate in today’s charged political atmosphere.

We can imagine how those same artists would portray homelessness in LA today. Would they use the same images our local government leaders use when they trot out smiling, clean, happy newly housed people, or would they paint people abandoned to the streets, living in filthy encampments? Would they try to depict shelters where families enjoy communal meals, or expose the barbarous living conditions in most of them? Would they create sunny murals that make us think LA’s homelessness system is working, or show the brutal realities of what it means to be homeless in Los Angeles? If they chose to paint the reality, would leaders allow it, or try to suppress the images as they did in 1934?

I think we know the answer to that question. For years, leaders have carefully crafted an image of “compassionate response”, where unhoused people are treated with dignity and provided the services they need to get off the streets. In this worldview, outreach teams fan out across the city to meet people where they are, connect them with services, and help them move to shelters (or Inside Safe rooms). Shelter workers address the physical and mental needs of their clients by managing facilities with consistent support programs. Once housed, people continue to receive support services and of course make themselves available for press opportunities orchestrated to make programs look like ringing successes.

Depicting reality would be far darker. The medical system that is supposed to keep unhoused people healthy and out of emergency rooms is so broken, medical teams who want to provide ongoing care cannot do so without breaking state insurance regulations. Medi-Cal requires patients to see their primary care physicians for a referral to specialized services. Of course, most homeless people have no way of connecting with their PCP’s, so they can’t receive vital ongoing care like dialysis. Street medicine doctors can only try to contact primary care doctors or give patients stop-gap care; inevitably, many unhoused people wind up in emergency rooms with serous illnesses. It would make far more financial and humanitarian sense to allow street medicine physicians to act as PCP’s and refer patients directly to Medi-Cal providers for necessary services, but state law needs to be changed first. The result is thousands of desperately ill people left on the streets, where at least seven die each night.

Leaders might want artists to paint idyllic pictures of happy, clean, well-fed people restoring their lives in a safe and supportive shelter system. If the artists chose realism, they may depict conditions in places like Riverside Bridge Home in Los Feliz, where investigative journalist Sam Quinones found a hellish world of sex trafficking, drug dealing, and violence, including the recent killing of a former resident. We need to understand the person who was killed outside the shelter wasn't a consequence of the shelter system, he was a product of it. Despite being in and out of shelter for months, the man never received the support he needed. The system creates an environment where people in need of serious mental health and addiction issues are dumped into unsafe facilities.

Even though it cost the life of at least one person, Councilmember Raman refuses to employ reasonable security measures at the shelter--although she granted the NPO she founded a non-bid contract for "ambassador" services. In Raman’s worldview, it is far more important to make shelters look like safe havens for people temporarily down on their luck, rather than the bedlams they are. It is also important to make sure large corporate nonprofits like PATH continue to be paid despite the abysmal way they manage shelters. Admitting shelters may harbor people who have serous mental health or addiction problems would also be admitting that homelessness isn’t just a housing issue, something most advocates refuse to concede.

Indeed, most of the DSA-affiliated members of the City Council, as well as--to a large degree-- Mayor Bass, have a worldview completely detached to the reality in which the homeless and many residents must live. The Mayor refers to encampments being “communities” rather than filth-ridden warrens where medieval diseases and crime are virulent. As San Deigo’s District Attorney reported in 2022, the unhoused commit crimes and are crime victims many orders of magnitude higher than housed residents. Sam Quinones, writing for Los Angeles Magazine in 2023, vividly described the appalling conditions on the streets of Skid Row. Advocates also insist the unhoused are victims of an unjust economic system, where they cannot afford rent and fall prey to avaricious landlords. In this narrative, once people become unhoused, they often turn to substance abuse or suffer from debilitating mental health problems. Yet a comprehensive survey of homeless people by the UCSF Benioff School showed most unhoused people had life histories of mental illness or substance abuse before they became homeless.

How far are local leaders willing to go to defend a system this broken? For starters, Mayor Bass has steadfastly refused to embrace any kind of reform. She opposes defunding LAHSA. She publicly parted with Governor Newsom when his office released a model ordinance for encampment clearance last May, claiming the state was being cruel and criminalizing homelessness. She tried to shrug off the damning court-ordered assessment from Alvarez & Marsal as “concerning” but not accurate. But perhaps there is no better example of the extreme measures the City will take than the $1.8 million it paid law firm Gibson Dunn & Crutcher for two weeks’ work. As reported by the Westside Current, the billing included several charges for meals, at least two of which exceeded $400. The City Attorney’s spokesperson was effusive in praising Gibson Dunn, lauding their ability to prepare for a trial on short notice. In the City Attorney’s worldview, spending $1.8 million was well worth preserving the myth that the City is running effective homelessness programs. As the Current’s article pointed out, Alvarez & Marsal found serious problems with financial management, including $2 billion in funding that cannot be accounted for. In addition, as I was quoted in the article, $1.8 million is only the beginning; much more will be spent if the case comes before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

I reviewed Gibson Dunn’s invoice. Besides many pages of redacted legal charges, the bill included such curiosities as a case of water and “several bags of food” for $46.23; $53.40 for picking up and delivering two large binders; and $392.60 for dinner after a court hearing, which is an interesting charge since it was outside of normal working hours. One would think after billing the City $1,300 per hour per attorney, they could afford their own dinner.

People familiar with legal billing tell me none of this is unusual. Really, it isn’t the exorbitant hourly rates nor the charges for milage, meals, and copying that should concern taxpayers. That is the price one pays for legal representation from high-profile firms. But it takes a particularly deranged kind of logic to justify spending millions to protect a warped worldview where people beset by serious mental illness and bedeviled by addictions are reduced to symbols of economic injustice. This worldview absolves the unhoused of any responsibility, both for the cause of their homelessness and for efforts to lift themselves out of it. They must be eternal victims. Unlike the workers in the Coit Tower murals who rose up to defend themselves, in Los Angeles, the homeless must remain passive until they are housed by a benevolent government who will tell them where and how they must live.

We must wonder what someone like Councilmember Raman sees when (and if) she passes by the Riverside Bridge Home. Does she see the desperation, violence, and abuse? Does she see taxpayer money wasted on ineffective shelter management? Does she see human beings trapped in an endless cycle of shelter, housing, and a return to the streets? Or does she see an opportunity to score talking points about social inequities and the need for housing everyone at taxpayer expense? Whatever she sees, and however she and other so-called advocate choose to define their world, the cold reality is that they champion a system that dehumanizes its victims, diverts billions in revenue to relatively few large providers, demonizes critics, and ensures a continual supply of new “clients”. It is hellishly efficient.

In 1934 San Francisco, a group of dedicated artists had the talent, integrity and bravery to picture the world as it was. They were supported by a government that allowed them the freedom to express the reality of Depression-era America. In Los Angeles, we are faced with a government that sees a world that simply does not exist, and that will go to any extremes to defend that worldview.

(Tim Campbell is a longtime Westchester resident and veteran public servant who spent his career managing a municipal performance audit program. Drawing on decades of experience in government accountability, he brings a results-driven approach to civic oversight. In his iAUDIT! column for CityWatchLA, Campbell emphasizes outcomes over bureaucratic process, offering readers clear-eyed analyses of how local programs perform—and where they fall short. His work advocates for greater transparency, efficiency, and effectiveness in Los Angeles government.)