Comments

GUEST COMMENTARY - In the Twitter Age of discourse, people talking about their neighbors sound like my drunken grandpa.

“Those people aren’t even from this town.”

“We were here first!”

“We need to round up the homeless and put them in the desert.”

I’ve heard these outbursts from residents during my time with the city, and before.

I would argue their ire is misguided, yet people are right to be frustrated with key issues on Los Angeles living: high rents, unbalanced density, barriers to home ownership, and how easy it is to become homeless.

People want a major change in our housing system. And they want it now.

Not so fast.

First, we need to ask some hard questions.

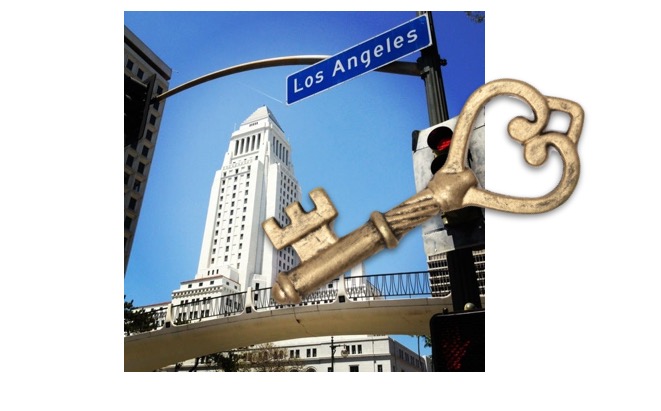

Who exactly has a right to Los Angeles?

Is it only for those with unbroken lineage from the Mexican pueblo? Is it just for homeowners with no mortgage? Can a single mother late on her rent call herself an Angeleno?

What about the 40,000 homeless people? If someone cannot afford what’s widely accepted as shelter, should they be locked out of the city?

Is Los Angeles best fit for an alcoholic with a historic house in Hancock Park? Is that better than a sober senior living in the bushes off of PCH?

Should the poor be confined to studio apartments crammed up against the bustling 110 interstate?

Why do the residents of Bel Air get a quiet sky, while those in West Park Terrace hear daily jet engines from LAX?

Is wealth the key to living by the beach or on a high hill?

It certainly was in the past. Rich families like Bixby, Dominguez, Sepulveda and Temple held massive chunks of Los Angeles and got to live on the best parts. This regime continues today. We both know that baristas and janitors don’t own the mansions on Mulholland. The elite estates belong to mega money makers — the executives of billion dollar companies or the top surgeons that fill the famous with botox and silicone.

But if we look further into our land’s history, the first Angelenos like the Chumash or Tongva handled living arrangements differently. Many tribes shared stewardship of the land; the concept of an individual “owning” a piece of Earth wasn’t recognized as a possibility. The first peoples knew that we are just one kind of creature living here anyway.

Coyotes, raccoons, bees, bacteria et cetera have lived in Los Angeles for millennia; they would like to stay. And we’d better hope that they do stick around.

Even if we consider some of our nonhuman neighbors to be pests, we need them to make the city habitable. Our fellow organisms provide critical resource processing that even the richest entrepreneur could not afford without going bankrupt. The gift of chemical degradation alone, given to us by other creatures, is worth billions of dollars annually.

This city needs us to think deep and carefully — something human beings are not always the best at. It is much easier to point the finger at the homeless or newcomers and blame dumping, gentrification and more on them.

If we want our housing system to get better, we should gradually return to the tradition of our tribal forerunners. The modern term for this is living in a Community Land Trust, which is a model that is slowly growing in our country. These trusts are often legally formed as non profit organizations that hold and manage property for the residents. People can still own homes but the surrounding area forms a holistic community.

Expanding community land trusts in Los Angeles will let us more equitably live together, including with our furry/feathered friends. Gone will be the days of concentrating a group of people to the worst parts of town because they have dark skin, or are poor. We can democratically decide where we want multistory buildings, single family homes, nature reserves and commercial corridors. Our residential landscape will sustainably improve if it is decided by an informed vote by all, rather than the big bucks of a few.

It’s time to make a new set of keys to the City of Angels.

(Eramis Goodspiel <[email protected]> was born in 1985 and attended LAUSD schools as a minor; he graduated from the University of California system. He writes anonymously to not jeopardize his employment with the City of Los Angeles.)