CommentsVOICES-Imagine that after a long career in building design and a list of over 4000 buildings in Los Angeles that people would remember an architect for his ability to sketch upside down.

Paul Revere Williams (photo, above) learned this skill early out of necessity. As an African American he could not sit side by side with white clients but faced them from across the table: it was the old napkin trick. Another thing that Williams did to gain his clients’ business was to design with a quick turn-around. Sometimes he would work 24 hours at a stretch.

The clients varied. A house for Frank Sinatra as well as one for Lucille Ball, but also the Nickerson Gardens, a planned community of 1,066 units built in Watts as a public housing development under the Housing Authority of Los Angeles in 1955. He is pictured in a photo standing with William Pereira and Welton Becket in front of the theme building and restaurant that looks like an elevated spaceship at LAX. Built in 1961, the airport was a joint venture and he was probably not responsible for the design of this building, but it shows his prominence at that time as a member of the Los Angeles City Planning Commission. And earlier, around 1924, on Warner Drive in Carthay Circle, a community adjacent to my own, he did two houses on shallow lots with their backs to the high-rises on Wilshire Boulevard. The irony is that under the covenants, codes, and restrictions in those days (the CC & R’s,) Williams would not have been able to purchase property in what was then known as Carthay Center.

One of the houses he designed in today’s Carthay Circle is Tudor eclectic in style. It has a steep pitched front-facing gable that is supported on shaped beams overhanging the ground floor. Bay and oriel windows and a variety of other period details abound. The buildings are a tour-de-force designed when the architect was only 30 years old. He had just graduated from the USC School of Engineering and would go on to design the Beverly Hills Hotel, a Christian Science Church complex, and the historic 28th Street YMCA. The Y swimming pool was originally built in 1926 to serve the African American residents of the Adams district who were excluded from swimming in public pools until 1931. I toured the building with the LA Conservancy after it and a new addition were recently converted into 49 units of low-cost housing, each with a full kitchen and bath.

One of the reasons perhaps that Paul Williams is not better known to me in spite of his long list of accomplishments is that his records, including letters, drawings and photographs were stored in a bank that was destroyed by fire in 1992 during the uprising following the jury’s verdict in the Rodney King case. But the story is more complicated than that.

Institutional racism

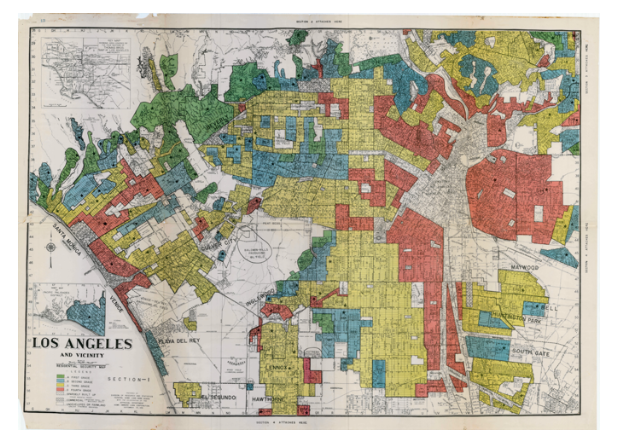

I started to write this series of short articles about architects who have contributed to the neighborhood in which I live in order to promote the Office of Historic Resources and in particular the three Carthay neighborhoods that have combined to form Historic Preservation Overlay Zones (HPOZs) here. But this was before the latest marches to protest the injustice done to George Floyd and the many other victims of police brutality. Now, inadvertently, I am writing about institutionalized racism in Los Angeles. Online, it’s possible to view the maps produced after the National Housing Act of 1934 and the creation of the FHA (see above). People needed loans to build housing and the maps were coded in colors to create homogeneity with respect to risk. Banks would use the maps produced by the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation to avoid making loans to areas colored in red; hence the term “redlining.”

It was difficult for certain residential areas to obtain loans to build and then to maintain housing. Neighborhoods became segregated and are racially divided to this day making disparity and inequality an enduring feature of LA life.

We cannot look at our architectural heritage without opening ourselves to the history of ethnic communities and architects like Paul Revere Williams who have contributed to it in such a lasting and important way. The time is long past due to remedy our ignorance and to reform the institutions which perpetuate injustice.

(Peter Merlin is a long-term resident of Carthay Square in LA. He currently serves on the HPOZ Board for the three Carthays. He was formerly an LA architect and a docent at LACMA.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams

.