Comments

PLANNING WATCH - In Los Angeles the sidewalks are in dreadful shape because City Hall has not repaired them for many decades. According to Investing in Place, resident complaints about sidewalks take 10 years before the City finally makes repairs. Furthermore, Investing in Place contends that without well-maintained sidewalks, proper streettree and street lighting programs cannot succeed. Even though Los Angeles has one of the largest sidewalk networks in the United States, City Hall has no unified program to deal with them because an unenforced 1911 law requires property owners to maintain adjacent public sidewalks. As a result, the City Auditor reports that over half of LA’s 9,000 + mile sidewalk network is in disrepair.

In response to lawsuits against the City of Los Angeles from disability rights activists, the 2015 Willits Settlement court decision requires the City to invest $31 million per year in sidewalk repairs for 30 years. The eventual cost would be $1.4 billion, under a “Fix-and-Release” program that transfers repair responsibility to adjacent property owners.

Despite decades of negligence, City Hall has historically acknowledged that public sidewalks are public rights-of-way. This, however, changed when City Hall signed a 20 year contract with JCDecaux to post off-site commercial advertising on transit shelters in the public right-of-way. The company realized that millions of sidewalk users would see their ads. Furthermore, the contract ensured that half of the City’s revenues from the JCDecaux sign company were equally divided among LA’s 15 City Council districts. This provision assured the City Council’s support for the contract.

LA City Hall officials now treat public sidewalks as assets that can be leased to private sign companies to bolster the city’s budget. Alternatives, such as unmet promises to reduce the City's enormous police budget, have been forgotten, even though these potential savings are much greater than the revenue City Hall receives from sign companies that place commercial advertising on public sidewalks.

Why is this happening? LA’s sidewalks are in dreadful shape, yet the main concern of City Hall and State officials is to stop homeless people from sleeping in these public areas, not maintaining them.

When public officials allow sign companies to use LA’s public sidewalks for their business ventures, they must overcome two barriers:

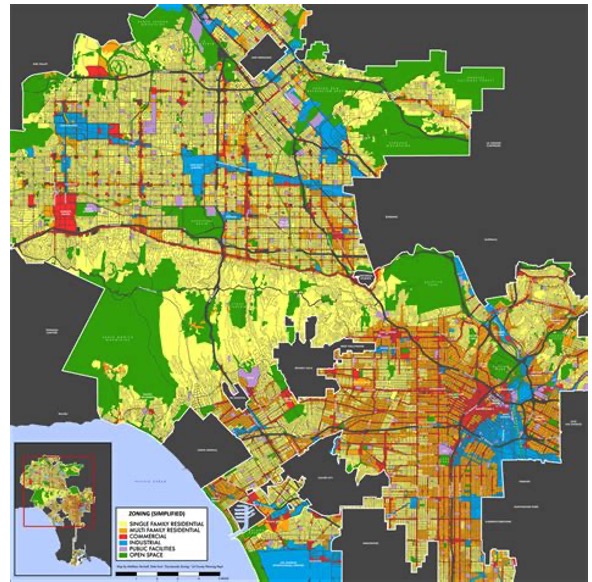

Barrier #1: Because LA’s Planning Department has taken so long to update the city’s 35 Community Plans, the City Council has adopted a host of overlay zoning ordinances, such as Specific Plans, Historic Preservation Overlay Zones, and Streetscape Plans.

Los Angeles has become a hodge-podge of zoning overlay areas.

Barrier #2: Most overlay districts include the public right-of-way, and the Board of Public Works has the authority to permit commercial signs in these areas, not the Department City Planning, even though Planning prepared and now administers every zoning overlay area. On December 16, 2022, the Board of Public Works approved a detailed contract with Tranzito Vector, an alliance of two private companies, to locate commercial signs on public sidewalks through LA’s STAP Program (Sidewalk and Transit Amenities Program.) These include 3000 bus shelter messaging signs, 404 kiosk signs, 44 locker signs, and 186 scooter dock signs.

Even though some of these off-site commercial signs could be located in LA City Planning’s (102) zoning overlay districts, they require special approvals from the Board of Public Works. For example, Los Angeles has 38 Historic Preservation Overlay Zones (HPOZs), and Tranzito Vector designated 37 of them for its off-site commercial signs. Furthermore, HPOZs include the public right-of-way, and their guidelines clearly state that these public areas are an essential part of all historic districts. As for signage, HPOZs only permit historic street signs. In addition, Section P of the HPOZ enabling legislation states that HPOZ ordinances include public areas, not only private lots.

“P. Publicly Owned Property. The provisions of this section shall apply to

any building, structure, Landscaping, Natural Feature or lot within a Preservation Zone which is owned or leased by a public entity to the extent permitted by law.”

Section Q., the next section of the HPOZ enabling legislation, specifies that projects not requiring a building permit, (e.g., commercial signs on the public right-of-way) are regulated by the City departments of Planning, Building and Safety, and Housing.

What, however, is the legal status of commercial signs proposed for public rights-of-way in non-HPOZ zoning overlay zones? In these cases, each overlay zone must be analyzed to determine if its provisions address commercial signs located in public areas. Since most of these ordinances are silent on this question, the argument of Tranzito-Vector’s City Hall enablers is that silence equals approval because off-site commercial signs are not prohibited. This assertion, however, is doubtful because silence does equal approval. It means the public still needs to determine if these ordinances otherwise address commercial signs in the public right-of-way. Here are some examples where commercial signs are not allowed, even if they are attached to transit facilities.

Pages 28-33 of the Westwood Village Specific Plan states that offsite commercial signs are prohibited, exactly what the Board of Public Works and Tranzito Vector would place on Westwood Village sidewalks in transit-related structures.

- The Atwater Village Pedestrian Oriented District also lists prohibited signs, which include flashing signs and off-site commercial signs. Despite these City Council-adopted restrictions, the Department of City Planning claims these signs are allowed in the Atwater Village public right-of-way areas because they are attached to transit shelters.

- The Sylmar Community Plan Implementation Ordinance also lists prohibited signs. These include “digital, flashing, animated, blinking, or scrolling signs or any sign that appears to have any movement.” Yet, the Board of Public Work contract with Tranzito Vector could allow Tranzito Vector digital signs in Sylmar’s public areas.

- The Venice Coastal Zone Specific Plan also has detailed development standards that apply to the entire ordinance area, not just private lots. These standards exclude billboards and roof top signs, but are silent on off-site commercial signs located in the public right-of-way. Since billboards are prohibited, they should not be allowed on transit structures.

- The Foothill Corridor Specific Plan includes the entire specific plan area, not just private parcels. Furthermore its Section 9 prohibits off-site commercial signs unless they replace an existing sign, which means that Tranzito-Vector commercial signs ought to be prohibited.

- The Granada Hills Specific Plan also covers the entire plan’s sub-areas. This City Council-adopted ordinance expressly prohibits commercial signs in the public right-of-way, as well as digital display ads. It does not contain any exceptions that permit these prohibited signs if they are attached to transit shelters. This is why this Specific Plan would not allow Tranzito Vector signs

- The Mulholland Scenic Parkway Specific Plan includes the entire plan area, which extends a half-mile on both sides of Mulholland Drive. This specific plan’s Section 7 contains detailed provisions for the public right-of-way, such as prohibiting sidewalks. It also states that any structures in the public right-of-way should be consistent with the natural appearance of the Santa Monica mountains and should not block views from Mulholland Drive. Clearly, Mulholland Drive should not be a candidate for Tranzito-Vector’s off-site commercial signs.

- The Park Mile Specific Plan includes amendments that address signage in the plan area, which extends from Highland on the west to Wilton on the east. In this public right-of-way area, the Specific Plan carefully regulations signage. Commercial signs can only promote existing businesses, which would therefore prohibit nearly all off-site commercial signs. In addition, signs that flash or blink are not allowed, as well as billboards and commercial signs placed on bus shelters. The signs proposed by Tranzito-Vector should, therefore, not be permitted.

- The USC Specific Plan's adopted Design Guidelines for University Park discourage billboards and offsite signs in public areas. The spirit of these Design Guidelines, approved by the City Planning Commission in 2012, would not allow the STAP program’s offsite commercial signs in the USC campus area.

- The Ventura/Cahuenga Boulevard Corridor Specific Plan is now being revised. The current version of this plan prohibits off-site commercial signs, which means that the proposed Tranzito-Vector signs should not be allowed, even if attached to transit shelters.

- The City Planning Commission approved the Pacoima Community Design Overlay District in 2003. Its design guidelines include the entire CDO area, including all public areas. Its guidelines stipulate that the Departments of City Planning and Building and Safety must approve all signs, and, “The CDO applies to the erection, construction, addition to, or exterior structural alterations of any building or structure, including, but not limited to, pole signs and/or monument signs located in a Community Design Overlay District?” While the CDO text does not specifically address Tranzito-Vector’s proposed off-site commercial signs in the CDO’s public areas, by inference this CDO would not allow them

- The Panorama City Center Streetscape Plan was approved by the Cultural Affairs Commission, City Planning Commission, and Board of Public Works in 2003-4. Its boundaries include all public areas. This plan does not regulate the private off-site advertising signs that are part of the STAP program. It does, however, state that one of the streetscape plan’s goals is to: develop the public right-of-way so its highlights the community’s presence, improve a sense of place, and work with commercial signage to enhance the business environment. There is no mention of off-site commercial signs placed in Panorama City’s public areas by a private sign company.

Most overlay zones targeted for STAP commercial signs on public sidewalks and bus shelters offer similar language. Their prohibitions must be carefully considered, not summarily dismissed to accommodate a private sign company and City’s intent to locate profitable off-site commercial signs in public areas, despite City Council-adopted or Commission-approved regulations that do not permit them.

While the City’s STAP Program runs for 20 years, if the program manages to provide Angelenos with shade and shelter for 3,000 transit stops, it still will have failed to upgrade more than half of LA’s existing transit stops. This minimal accomplishment reveals that the City’s intent was to create a revenue generating program, not a program that provides shade and shelter for transit riders.

Much of the information for this column was taken from a Citizens for a Better Los Angeles lawsuit opposing the STAP program.

BASED ON COMMENTS, I WILL POST FUTURE CORRECTIONS TO THIS COLUMN.

(Dick Platkin is a retired LA city planner. He reports on local planning issues for CityWatchLA. He is a board member of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA). Previous columns are available at the CityWatchLA archives. Please send questions to [email protected].)