CommentsPLANNING WATCH - Real estate is a highly profitable business, especially when its income comes from rents.

How profitable? RentCafe reports that the size of the average Los Angeles apartment is 790 square feet, and its monthly rent is $2,563. In some areas the rents are even higher. In Santa Monica the average rent is $3,740/month, and in West Hollywood the average apartment costs $3,260/month.

Other real estate companies report data similar to RentCafe. Apartments.com lists 22,000 Los Angeles apartments for rent. Their typical two-bedroom unit is 884 square feet and rents for $2,770/month. Their average three-bedroom unit has 1,148 square feet and costs $3,856/month. A similar company, ApartmentList, has also analyzed its own listings. Its average one-bedroom apartment costs $3,007/month, and its two bedrooms rent for $4,124/month.

Needless to say, the prices for these apartments scrape the heavens, and many other expensive apartments go unlisted.

If we turn from apartments to houses, the data is even more compelling. According to RedFin, the average sales price for a Los Angeles house reached $950,000 in December 2021. One reason for these inflated prices is corporate real estate companies that buy into local housing markets, like LA’s. Their financial model is straightforward. They pay cash and easily outbid families hoping to buy a single-family house. These companies then collect rents from former homeowners, until the new landlords can sell these appreciating assets. According to US News and World Report, about 15 percent of homes are now bought by major financial companies, especially Blackstone. Since the 2008-2010 Great Recession, these companies have switched the business model from owning apartment buildings to buying, renting, and eventually flipping single-family homes.

According to Slate magazine, these companies buy houses that are relatively inexpensive, mostly built in the 1970s, likely to appreciate, and located in growing urban areas. Slate also reports that this financialization of housing is “part of a long-standing trend: As inequality in the United States increases, the financial elite invests less in the types of things that could create jobs, like R&D or new factories, and more into directly extracting wealth from the working class [through rental housing].”

How much does the finalization of both apartments and single-family homes generate for these corporate investors?

The real estate data firm Zillow reports that in the United States the total annual rent paid by tenants is now $4.5 trillion. In Los Angeles in 2019 tenants shelled out $39.2 billion (not million) in rent. This is nearly four times the annual budget of the City of Los Angeles.

When real estate projects, like these, generate profits, they transfer wealth from the middle class and poorest members of society to the wealthiest. Quite literally, the rich get richer and the rest get poorer, a process easily observed in Los Angeles County, where 54 percent of residents are renters, over half of whom are rent burdened or severely rent burdened. To ensure they have a place to live, these tenants are forced to make significant cutbacks in food, clothing, transportation, and health care.

What sense can we make about the high price of housing in LA and the enormous amount of rental income transferred upward to real estate investors?

First, the housing crisis may hurt a major section of the population suffering from belt-tightening, overcrowding, rent-gouging, homelessness, living in cars, and couch surfing, but it is highly rewarding for investors who own rental units, especially large companies, like Blackstone.

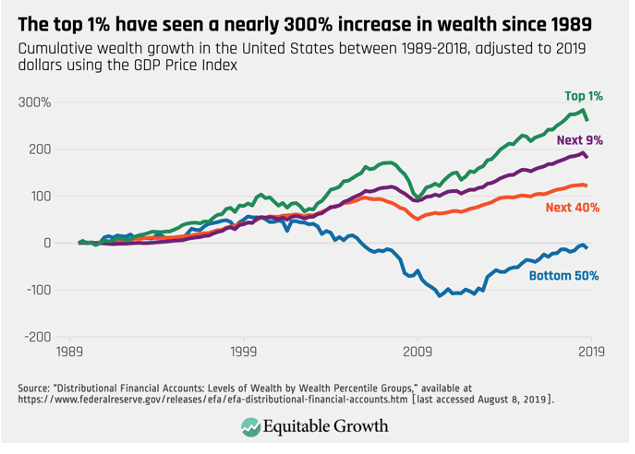

Second, according to Jacob Woocher in Knock-LA, the extraction of rent is a transmission belt of wealth from poor neighborhoods to well-off ones. More particularly, he identifies major Los Angeles landlords whose incomes originate in low income neighborhoods far from where they live. As a result of both rent and wage-gouging, economic inequality in the United States is now similar to that of the Gilded Age (1870-1900).

The financial structure of housing in Los Angeles, like the US as a whole, reflects the country’s unequal class structure, which means that income and wealth gaps have substantially increased over the past three decades.

But cities like Los Angeles could take immediate steps to stop reinforcing these trends.

- Like the 1930s, Los Angeles could again build its own non-market public housing, funded by a restoration of the Community Redevelopment Agency housing program, adoption of a Transaction Tax on large real estate projects, and/or other potential funding mechanisms.

- Cities could also adopt a cutoff date of 1995 instead of 1978 for LA’s Rent Stabilization Ordinance, as well as eliminate vacancy decontrol.

- Cities, like LA, could adopt Inclusionary zoning ordinances that require inspected affordable units in all new multi-unit residential projects.

- Instead of up-zoning commercial zones, cities could down-zone them to encourage real estate developers to apply for density bonuses. After that, cities should physically inspect these projects to verify that landlords are charging low-income rents to their HCID-vetted low income tenants.

- Another option to reduce real estate speculation is for cities to increase transaction taxes on large projects. For example, a proposed ballot Initiative that I previously wrote about would charge four percent on real estate projects valued between $5 to $10 million, and 5 percent on projects worth more than $10 million. These projects comprise 3 percent of all real estate investments in Los Angeles, and these fees would generate $800 million per year, dedicated to the preservation of existing low-priced housing and the construction of new non-market public housing.

In combination, or separately, these legislative actions could slow down or reverse the redistribution of wealth through rental housing. Some critics contend that such a ballot Initiative would instigate class conflict, but this is a serious misreading of what is already taking place. The redistribution of income and wealth upward through rent has been gathering steam for four decades. The municipal policies listed above would only curtail alarming trends underway since the 1980s. While speculative real estate investors would not take kindly to legislation that impinged on their highly lucrative business model, the beneficiaries, those whose rents exceed 30 percent of household income, could stop rationing food, clothing, transportation, and health care.

If these policies result in downward redistribution, back to the levels of the early 1980s, then I say the sooner the better.

(Dick Platkin is a former Los Angeles city planner who reports on local planning issues for CityWatchLA. He serves on the board of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA) and co-chairs the Greater Fairfax Residents Association. Previous Planning Watch columns are available at the CityWatchLA archives. Please send questions and corrections to [email protected] .)