CommentsGELFAND’S WORLD--There have been a lot of songs and stories about the early days of Hollywood, but what about before Hollywood was Hollywood -- when it was still the wild west? What about the original cast of characters -- the real characters, not the ones on screen -- people who were by parts murderous, playful, scheming, loving, and thieving? In today's account, we are interested in the people who populated the area to the west of Western and to the north of Wilshire. There is a clue to our story in the name Eugenio Plummer, after whom Plummer Park in West Hollywood is named.

In the late 1930s, Plummer -- by then in his 90s -- sat on a bench in newly established Plummer Park and told his life story to a writer for the LA Times. The story was eventually published as a book in 1942: Senor Plummer: The life and laughter of an old Californian. The book tells of Plummer's experiences as a young boy in California right after the gold rush, his early years in Mexico, and eventually his teens and adulthood in a rapidly growing Los Angeles. Plummer could obviously spin a yarn with the best of them, but his stories make for interesting reading, whether or not they adhere strictly to literal truth. (Photo left: Eugenio Plummer 1939)

In the late 1930s, Plummer -- by then in his 90s -- sat on a bench in newly established Plummer Park and told his life story to a writer for the LA Times. The story was eventually published as a book in 1942: Senor Plummer: The life and laughter of an old Californian. The book tells of Plummer's experiences as a young boy in California right after the gold rush, his early years in Mexico, and eventually his teens and adulthood in a rapidly growing Los Angeles. Plummer could obviously spin a yarn with the best of them, but his stories make for interesting reading, whether or not they adhere strictly to literal truth. (Photo left: Eugenio Plummer 1939)

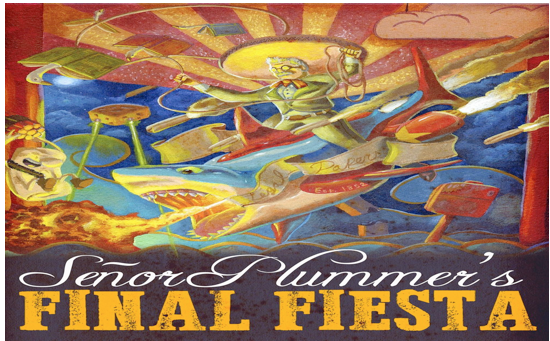

Out of this book comes a new theatrical production by the Rogue Artists Ensemble titled Senior Plummer's Final Fiesta. The play, as performed on Saturday, takes advantage of Plummer Park itself in order to pull off an exploration using immersive theater techniques, that is to say, a performance that moves from place to place (and even from building to building) and includes direct interaction between the actors and the audience.

It is, rare though this may be, a celebration of the location in which it is performed, as well as of the person from whom the location takes its name.

This performance couldn't help but be a bit surrealistic. Imagine an early scene in which the full cast are seated in a line, facing the audience. One by one, narrators come to the podium and tell us something about the characters. We are introduced to the young Eugenio Plummer talking to his mother. After a few moments, the narrator says, as if reading from a film script: "the mother turns around, exchanging her wig, and is now the judge."

As this opening scene develops, we are subjected to many such transitions, each described verbally, leaving the completion of the scene change to our imaginations. It's like having the script and observing a live reading at the same time. This use of transition by imagination worked well for Saturday's audience.

Curiously, this approach was not entirely intentional on the part of the producers. As assistant director Julia Garcia Combs explained, the company was presenting this version of Senor Plummer's Final Fiesta as a work in progress, intending to develop it into a completed work that includes changes in costumes and photographic backgrounds. Maybe this would work, but why do it? Why give up on a technique that builds on an honored tradition (think Wilder's Our Town) and which pulls the audience into the performance as active participants. If nothing else, it makes our imaginations work. As performed, it was the soul of immersive theater.

In presenting Final Fiesta as a work in progress, the writers and directors used a range of tricks, gimmicks, and traditional approaches. We begin by assembling as an audience on the lawn in Plummer Park, where a life-size puppet is seated on a bench. The puppet is Plummer in his 90s, being controlled by three masked handlers. He is joined by the Times writer, who introduces the audience to the simple facts that this is 1937, that the park is being named after Plummer, and that Plummer will be allowed to live in his house for the rest of his life in spite of the fact that he no longer owns the land. The newsman is the author who will publish the completed volume of Plummer's life in 1942.

From there, the actors present a series of stories that are lifted, sometimes nearly literally, from the pages of the book.

There is one complication with presenting a real person's story on the stage, no matter how fancifully embroidered. Real life does not necessarily follow the rules of Greek tragedy or Elizabethan comedy, which involve artfully contrived story arcs leading to inevitable results. What would Hamlet be if the prince had lived to a comfortable old age? The Rogue Artists Ensemble handles this problem by presenting Plummer's comfortable old age right at the very beginning, getting it out of the way and simultaneously letting us know that this play will contain elements of melodrama and comedy with perhaps the least little bit of tragedy.

The play then jumps around in time, presenting moments from Plummer's youth and adulthood without obvious structure.

One of the more interesting parts is Plummer's telling of his meeting with Helen Hunt Jackson, the author who was to write the novel Ramona. Ramona was the 1884 tear jerker that sold copies by the carload and became part of California mythology. There is still a Ramona pageant in Hemet (since 1923) even to this day. In his memoir Plummer claims that Helen Hunt Jackson visited him at his home while she was working on Ramona. As played amusingly by Cristina Gerla, the author asks -- and then learns in a fairly direct manner from Plummer -- how the Mexican and Native American cultures engaged in courtship.

It is an interesting coincidence that the book Ramona was affected (if it really was) by this early Hollywood resident named Plummer, even if it wasn't really Hollywood in those days, because Ramona became one of the most popular topics for the developing Hollywood movie industry. Ramona has been made into a movie 5 times, beginning with D.W. Griffith's short film, and reaching its high point with the Dolores Del Rio feature film.

Not all of Plummer's reminiscences are historic or even all that interesting, but this theater company tries to make a go of them. One story lifted directly from the book is essentially an extended fart joke, based on a story in which Plummer constructed an early version of the whoopee cushion (in case you were interested, made from a cow's bladder) and used it to embarrass a couple of women at a fiesta. The cast played this scene so well that the audience laughed vigorously, but perhaps this was due to the surrealistic elements -- the three actors in the scene are buffeted about by powerful winds, holding onto the furniture for dear life.

We should mention that in the final scene -- Plummer's grand fiesta -- the events were accompanied by the Mariachi band La Victoria (photo left) , an all-female group that plays with great skill and musical style and has a weekly gig at Las Perlas downtown.

We should mention that in the final scene -- Plummer's grand fiesta -- the events were accompanied by the Mariachi band La Victoria (photo left) , an all-female group that plays with great skill and musical style and has a weekly gig at Las Perlas downtown.

In discussing the performance, members of the cast and the assistant director made clear that this was still a workshop, and that they are interested in developing a fully formed version. This could become a contribution to southern California history in the sense that it brings some of our mythology to life. It should be pointed out that esteemed critic D.J. Waldie has taken a crack at the book, considering it from a historically critical standpoint. Waldie treats Plummer as an Anglo (despite the book and this production playing up his connection to Mexican culture). Waldie's piece is worthwhile reading for those interested in how California history has been portrayed in books and newspaper columns over the years.

I should like to come back to a few thoughts about what made this event worthwhile. As the assistant director explained, this is in some sense a memory play. You might see it in the same sense as Tennessee Williams' Glass Menagerie. As I mentioned above, the treatment of script directions was unusual but successful. But mainly, the use of surrealism, puppetry, and people played as cartoon figures made for what we used to call a mind bending experience. In one scene, a little box is supposed to be a courtroom. The litigants are portrayed as wolves and sheep who speak in mixes of animal and human voices. Meanwhile, the audience follows by looking through portholes in the walls.

Oh yeah, there was also one man with the head of a shark. He represented a major character in Plummer's book, the land shark. This is Plummer's term for the speculators of the late 1800s who took land away from its rightful occupants by taking advantage of the loose legal structures in existence at the time. The book expresses enduring anger against the land sharks that the workshop performance pretty much lets go. Instead, the performance concentrated on Plummer's assistance to the downtrodden as a courtroom translator in a time of multiple languages including native American dialects.

Senor Plummer's Final Fiesta used three young men (and one puppet) to play the part of Plummer in successive scenes. Tyler Bremer played an aging Plummer with energy and enthusiasm. In conversation, he explained that he got his start in theater with the Four Clowns, a company that CityWatch has covered extensively. Christina Gerla played not only the mother but Helen Hunt Jackson and a court litigant who spoke sheep rather than human. Christopher Barajas and Mariux Ibarra contributed ably, as did, indeed, the entire cast.

(Bob Gelfand writes on science, culture, and politics for CityWatch. He can be reached at [email protected].)

-cw