‘When School Preempts Summertime’-- An Open Letter to LAUSD Board President Zimmer

TURNING UP THE HEAT-I’m agin’ it. Really, really against it. I oppose force-marching our school-aged children back inside any Institution of Learning during their traditional months of summer-break. Our kids deserve a rejuvenating summer and the LAUSD Board of Directors should vote to recess school until after Labor Day.

How many ways can I justify my adamancy?

Preparation: There’s this argument that our kids “have” to be in school ever-earlier in the school year in order to allow our AP-taking, uber-achieving, uber-scared High School upper class students more time to study for their AP tests.

But wait a minute. Weren’t we assured six ways to Sunday that no one is going to “teach to the test?” This is the definition of “teaching to the test” – from the get-go! You’re structuring the very calendar of school to accommodate a test, and a test-taking paradigm, and a system of testing via a private, commercial, test-selling enterprise, constituted exclusively for the purpose of ginning our kids’ mental and emotional status into near-constant, hyper-jitterfied test-mediated terror.

And it’s not enough that they feel this way in real time, but do we have to extend their state of utter anxiety even deeper into the prequel-summer of their school year? These are tests that aren’t even their own teachers’ doing or their own course work’s material. These are tests created for a class which is wholly and entirely constituted for the purpose of taking – which is to say “buying” or “taking from parents (or school systems) the money for” … these AP tests.

These aren’t tests used to assess mastery of a body of material. These are tests created for the purpose of giving and taking these tests.

And now, not only is the test, the curriculum and the class itself supposed to kowtow to the Test, but so is the entire structure of the kids’ school year.

And more, the stricture applies not only to the kid taking the test, but to the kid’s entire family: Mom, Dad, siblings and other relatives. And to all the workers of all the school system. And to all the workers of a society formerly structured to serve a different school-year schedule (camp, holidays, sports, etc.)

Kindergarteners’ lives and their relationships with their families are dictated by a test company’s ceaseless campaign to ensnare more and more students in the maws of their life-eclipsing, test-taking juggernaut.

Basta.

Enough pretending that we’re not “teaching to the test.” The imperative of this test has saturated the structure of our very society. These tests have gone far beyond simply being taught to, they’ve entrapped the very prerogative of our social structure since the School Board now uses as partial-justification for the accelerated start date the need to allow our kids extra time to study for these tests.

…and that’s just one of the objections.

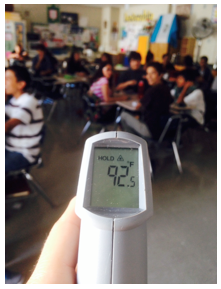

It’s Hot Out: It can’t have escaped anyone’s notice that temperatures in the northern hemisphere peak during summertime. And we live in a desert where the effort to control indoor climate is especially resource-intensive and hard to justify.

It’s Hot Out: It can’t have escaped anyone’s notice that temperatures in the northern hemisphere peak during summertime. And we live in a desert where the effort to control indoor climate is especially resource-intensive and hard to justify.

Just think about the system-wide resources necessary to adequately illuminate and subsequently cool the classrooms housing upwards of a half million children? Plus all their teachers and support staff. This is not a trivial exercise. It’s expensive, it’s environmentally unprincipled, it’s wasteful and it’s needless.

Everyone knows our collective sympathy for some other person’s child often falls short when the public purse is at stake. But what about the adult teacher tasked with shepherding that child into a mutually-acceptable state of productive citizenry? How unconscionable is it to ask a portly, middle-aged altruist to teach a roomful of 50 pre-pubescent bundles of unrejuventated energy? It’s a chilling sight to witness these teachers, fagged in their 110-degree classrooms, defeated by the children careening in obeisance to their unspent, youthful ebulliance. No one learns, no one is even able to teach, no one benefits, and much harm is achieved in stress-shortened lives, non-renewable energies squandered, bad habits engrained, and ill-temper engendered. Lose-lose-lose-lose-lose … to the nth power.

And all this to what useful end???

I’m a Partner In This Child’s Upbringing. It may take a Village but it takes a family, too. It’s my prerogative to spend some time with my children. And it’s theirs to stew in the muddle of their family’s, as well.

We’ve so amped the eclipsing power of the school to command our child’s time during the school year, with hours upon hours of schoolwork and ever-increasing course requirements translating to school credits and course hours, along with the tyranny of “choice” that forces endless commuting hours, even as subsidized busing (“transportation-dollars”) becomes increasingly elusive … all these demands on our children’s brief childhood drain them of the time just to be enfolded by us, their family.

Non-existent summers mean kids grow up without visiting their cousins, reveling in that odd Uncle’s prejudice, appraising an eccentric Auntie’s politics. Last on the list and preempted by foreshortened time, are moments that may be lost to no good end but you’re still breathing the same air in the same room as your raging adolescent. When tempers flare and connections fray, sometimes the most potent medicine of all is to simply share oxygen with no ulterior purpose whatsoever. No homework, no housework or work-work, no exhorting. Just being.

When LAUSD forces our kids back to school in the middle of the summer, they deprive them of us; it deprives our society of them and sells their future short.

There’s nothing I love better than a good book, but sometimes you need to pick it out all by yourself. That’s what summertime’s for.

Tell our schools to back off and give our kids the rest of their summer back!

Call your LAUSD board member and register your opinion on the 2017/18 school calendar change.

Here’s the contact information for the seven LAUSD Board Districts. Locate yours here:

Steve Zimmer (BOD President), District 4

213-241-6389; [email protected]

George McKenna, District 1

213-241-6382; [email protected]

Monica Garcia, District 2

213-241-6180; [email protected]

Monica Ratliff, District 6

213-241-6388; [email protected]

Ref Rodriquez, District 5

213-241-5555; [email protected]

Richard Vladovic, District 7

213-241-6385; [email protected]

Scott Schmerelsom, District 3

213-241-8333; [email protected]

Please note: A petition was opened in 2014 and 2015 by parent Morina Lichstein, who recently updated the already extensive and interesting background information stored at these links. Rather than open a third petition re-demonstrating the empirically obvious, that thousands upon thousands of families are dismayed by this policy, this time around it may be most effective to phone your board member directly.

(Sara Roos is a politically active resident of Mar Vista, a biostatistician, the parent of two teenaged LAUSD students and a CityWatch contributor, who blogs at redqueeninla.com) Edited for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

The La Brea Willoughby Coalition (“LCW”) neighborhood is a microcosm of these dynamics. Four SLS projects proposed and approved within a one-block area resulted in loss of affordable rent-control units on all project lots. The projects also resulted in several appeals and two lawsuits in which LWC prevailed.

The La Brea Willoughby Coalition (“LCW”) neighborhood is a microcosm of these dynamics. Four SLS projects proposed and approved within a one-block area resulted in loss of affordable rent-control units on all project lots. The projects also resulted in several appeals and two lawsuits in which LWC prevailed.

Criminals, however, do not care who owns property. It can be you, it can be me, or it can even be the State of California. When a criminal syndicate operates with the force of law, they take whatever they need. And, everyone else better shut up or else.

Criminals, however, do not care who owns property. It can be you, it can be me, or it can even be the State of California. When a criminal syndicate operates with the force of law, they take whatever they need. And, everyone else better shut up or else.

Describing the Congress, Cleghorn says, “The Congress is a once a year opportunity for Neighborhood Councils across the City to come together at City Hall for a day of education and communication for the entire NC System. It is an opportunity to speak one on one with our city's elected officials, department officials and each other. Also, to take advantage of a wealth of specialty workshops created by and for Neighborhood Council leaders. This year’s Congress seeks to advance the Neighborhood Councils’ advisory power needed for the enhancement and/or preservation of our communities.”

Describing the Congress, Cleghorn says, “The Congress is a once a year opportunity for Neighborhood Councils across the City to come together at City Hall for a day of education and communication for the entire NC System. It is an opportunity to speak one on one with our city's elected officials, department officials and each other. Also, to take advantage of a wealth of specialty workshops created by and for Neighborhood Council leaders. This year’s Congress seeks to advance the Neighborhood Councils’ advisory power needed for the enhancement and/or preservation of our communities.”

That city also maintains a directory of all public officials who have been contacted by a registered lobbyist and a list of all “subject areas” of concern reported by lobbyists. Lobbying firms are also required to report monthly, rather than quarterly as in Los Angeles.

That city also maintains a directory of all public officials who have been contacted by a registered lobbyist and a list of all “subject areas” of concern reported by lobbyists. Lobbying firms are also required to report monthly, rather than quarterly as in Los Angeles.

"We can think of climate change as the manifestation of disrupted carbon, water, nutrient and solar cycles."

"We can think of climate change as the manifestation of disrupted carbon, water, nutrient and solar cycles."

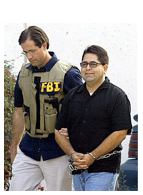

Bell--In 2010, a

Bell--In 2010, a  South Gate--Former city councilman, city manager, mayor and treasurer Albert Robles was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison in 2005 for public corruption, money laundering and bribery. Though several of the convictions were thrown out in 2013, Robles’ sentence was not reduced because of the seriousness of the bribery counts that remained.

South Gate--Former city councilman, city manager, mayor and treasurer Albert Robles was sentenced to 10 years in federal prison in 2005 for public corruption, money laundering and bribery. Though several of the convictions were thrown out in 2013, Robles’ sentence was not reduced because of the seriousness of the bribery counts that remained.