CAPITAL & MAIN SPECIAL REPORT--On election night last November, Nathan Damigo, a 30-year-old white nationalist and student at California State University, Stanislaus, met up with friends in the Northern California city of Folsom. As they bounced from bar to bar, it became clear that Donald Trump was outperforming most polls; when the election was called for the former reality TV star, Damigo and his buddies were euphoric. On the drive home, still buzzed by the victory, Damigo pulled out a bullhorn and shouted at passersby in the street, presumably those with darker skin than his, “You have to go back! You have to go back!”

“Trump’s election has been a major boost to morale,” he later told an interviewer. “Something is happening. Things are changing and it’s not going to stop.”

Damigo is part of an ascendant far-right movement, however uncoordinated, that sees the election of Trump as a sign that an extremist vision for the country -- which includes millions of undocumented immigrants deported and an open hostility to Muslims -- is moving from dream to reality. And this is not only about rhetoric. Since Trump’s election, groups that track hate crimes have reported spikes in the number of incidents, including within the deeply blue state of California.

Damigo grew up in San Jose, joined the Marine Corps after graduating from high school, and completed two tours in Iraq. He returned with post-traumatic stress disorder and in 2007, after an afternoon of heavy drinking in San Diego, pulled a gun on a cabdriver who he believed was Iraqi, robbing him of $43. He pleaded guilty to a felony count of robbery and spent five years behind bars, where he discovered former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke’s autobiography, My Awakening: A Path to Racial Understanding. Last March, he founded a group called Identity Evropa, geared towards attracting college students to white nationalism, a broad term whose adherents espouse white separatist ideologies.

Damigo has positioned himself as a sort of a West Coast sibling to Richard Spencer, the 38-year old who coined the term “alt-right” and who has become the country’s most prominent white supremacist, due in part to a video of him being punched by a presumed protester that went viral.

The pair appeared together at the Republican National Convention in Cleveland, where Damigo live-streamed the event for Red Ice Radio, a white supremacist network broadcasting from Sweden. And last November, two-dozen members of Identity Evropa traveled to Washington, DC for Spencer’s National Policy Institute conference, at which many attendees were seen flashing the Nazi salute.

When I reached out, Damigo emailed that he was on the East Coast in an area with limited cellphone coverage. Curious, I scanned Identity Evropa’s Twitter feed. Posted from early that morning were pictures of the group’s flyers plastered across the campus of Kutztown University, in rural Pennsylvania. The effort is part of “Project Siege,” which targets colleges with pro-white propaganda. A day earlier, the provost of Indiana University reported that the group’s flyers were posted on the office doors of faculty members of color. Also hit were schools in Illinois, Texas, Georgia and Virginia.

“Our members tend to be whites from diverse areas, because they have actual experience with multiculturalism,” he tells me over Skype. Damigo keeps his blond hair in the “Hitler youth” style -- longer on top, shaved on the sides -- and on the day we speak is wearing a black sweater and looks tired. Asked for an example of a problem caused by multiculturalism, Damigo pauses a beat. “You know, black people constantly being dicks to white people, starting fights with them, harassing them.” His answer to what he sees as the problem of multiculturalism, which he views as inherently anti-white, is as simple as it is quixotic: the creation of a white ethno-state for Americans of European descent. (Damigo doesn’t consider Jews to be white, and they are barred from joining his group. Asked recently about whether the Holocaust occurred, he declined to answer, stating that he’s “not a history buff.”)

Damigo says that the majority of Identity Evropa’s members are in California, but he dreams of taking his group, which he describes as “Identitarian,” national. “A lot of people started becoming interested in politics a year ago,” he says. “They knew something was wrong but didn’t quite get what. Advocating for whites is going to become normalized: People are waking up to subjects that were once very taboo.” Damigo first told me that over the past five months, Identity Evropa had signed up about five new members a day, which comes to roughly 750 members. A couple of days later, however, he estimated the membership at 300.

He likens the white nationalist movement to the early years of the gay rights movement. “Back then, if someone was homosexual and came out, they would be dealing with chronic unemployment and ostracism. We’re dealing with the same thing.” But he tells me that he sees signs that change may be on the way, accelerated by the election of Trump. “It’s starting to snowball.”

California is like America, only more so,” said novelist Wallace Stegner, echoing journalist Carey McWilliams’ earlier opinion that “Californians are more like the Americans than the Americans themselves.” California, McWilliams continued, “is the great catch-all, the vortex at the continent’s end into which elements of America’s diverse population have been drawn, whirled around.”

The state is solidly liberal, with political leaders who have promised to resist Trump’s agenda.

“California is not turning back,” Governor Jerry Brown declared last January in his State of the State address. “Not now, not ever.” When San Francisco International Airport erupted in protest after Trump signed his executive order targeting Muslims, Lieutenant Governor Gavin Newsom was there, shaking hands in the crowd and registering his dissent. And a week after Trump signed another sweeping executive order -- this one stepping up enforcement actions against undocumented immigrants-- the state took its first steps to create a “sanctuary state,” which would prohibit the state and its localities from enforcing federal immigration laws.

Yet California also has a rich history of right-wing extremism, xenophobia and racism, which it has exported, with varying degrees of success, to the rest of the country. Perhaps the best example is Proposition 187, which was overwhelmingly passed by voters in 1994. The law was drafted in part by a lobbyist with the Federation for American Immigration Reform (FAIR), an organization that seeks to severely curtail immigration to the U.S. and whose founder, John Tanton, believes that the U.S. must remain a majority-white state. FAIR is designated as a “hate group” by the Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), which defines the term as a group with “beliefs or practices that attack or malign an entire class of people, typically for their immutable characteristics.”

(Left, undated photo of KKK march, possibly taken in Santa Barbara.)

(Left, undated photo of KKK march, possibly taken in Santa Barbara.)

Proposition 187 prevented undocumented immigrants from receiving most tax-supported benefits, including medical care at publicly funded hospitals and the use of public schools. (It was immediately challenged in court and eventually declared unconstitutional.) Less remembered is that Prop. 187 also compelled all law enforcement agents and school officials to investigate the immigration status of individuals they believed might be in the country illegally, and to refer such individuals to both federal immigration agencies and the state attorney general. It was the mother of all anti-immigrant bills, from SB 1070 in Arizona to HB 56 in Alabama, a specter that continues to haunt our country as a new wave of raids takes shape.

Anti-immigrant and anti-Mexican sentiments go back much further than the mid-1990s, of course. For the first half of the last century, Mexicans and Mexican-Americans were forcibly segregated into second-class schools and shunted into fieldwork. When they attempted to organize for higher wages, they were met with violence from the state, surveilled by sprawling private spy networks or simply deported. Business owners posted “White Trade Only” signs in their windows, and care was made to prevent races from mixing in public facilities. For years the City of Orange, for example, allowed children of Mexican descent to use its public pool only on Mondays. The pool was drained on Monday night and cleaned and refilled on Tuesday, to protect white children from contamination.

Racial hysteria swept the state during World War II, this time targeting the Japanese. In January of 1945, the federal government reopened the West Coast to Japanese-Americans, who had been rounded up into internment camps three years earlier. Fearing anti-Japanese hostility, the government offered funds to any former internee who decided to remain east of the Rockies, but most elected to return. This unleashed what the War Relocation Agency characterized as a “widespread campaign of terrorism.” In the first six months, Japanese-Americans were targeted in 22 shootings and 20 cases of arson. Vigilantes burnt their sheds to the ground and fired bullets into their homes. Most of the violence was in rural areas, but not all. In San Francisco, the windows of a hostel sheltering Japanese were smashed.

The post-war period saw the resurgence of the Klan in California, in response to returning veterans of color who were impatient to finally live in the democracy they had fought for. In Fontana, 50 miles east of Los Angeles, an African American named O’Day Short moved his family into a new home in 1945. The house was south of Base Line Road; the saying around town was “Base Line is the race line.” Blacks were supposed to stay north of the road. A group of men, likely from the local KKK, visited Short and advised him to leave, but he didn’t budge. A few days later, his home was firebombed and Short, along with his wife and two young children, perished. A generation would pass before another black would buy property south of Base Line.

This sort of racial segregation was the rule in California, often enforced through restrictive housing covenants that forbade selling a property to a person of color. (Short was light-skinned, so may not have been identified as black by the seller.) In addition, California had a comparatively high number of “sundown towns”—white communities that barred blacks and other people of color after nightfall.

Damigo’s vision, then, of whites living apart from other races, does have a historical precedent, and his anxiety about the browning of the state comes from a deep strain of nativism. A century ago, boosters held up Los Angeles as a “city without slums” and “more Anglo-Saxon than the mother country today.” That Eden was soon spoiled, however. In 1928, a reporter for the Saturday Evening Post complained that the city was filled with “the shacks of illiterate, diseased, pauperized Mexicans” who breed “with the reckless prodigality of rabbits.” This invasion of foreigners -- forgetting for the moment that California was once part of Mexico -- is the animating force behind white nationalists like Damigo. They long for a past that never was, and he hopes to tap into the power of Trump’s ahistorical nostalgia. One of the posters that Identity Evropa posts on college campuses proclaims, “Let’s Become Great Again.”

In more recent decades, the state has cranked out a who’s who of notable racists and immigrant bashers. Richard Butler, the founder of Aryan Nations, spent decades in California before retreating to his compound in Idaho. Tom Metzger, who would launch White Aryan Resistance, got his start by attending John Birch Society meetings in Southern California in the 1960s. And it was a retired accountant from Orange County, Jim Gilchrist, who put out the call for armed volunteers, or so-called Minutemen, to patrol the southern border in 2005.

According to the SPLC, there are currently 79 hate groups scattered across California, the state with the highest number in the nation. (Florida is second with 63.) Many keep a low profile, but last year they were impossible to miss, as two brawls erupted between white power groups and much larger contingents of counter protestors. The first was a Klan rally in Anaheim, the second a joint rally between the Golden State Skinheads and the Traditionalist Workers Party. In each, multiple people were stabbed.

“California has been a cornucopia of extremism on all sides of the political spectrum,” says Brian Levin, who directs the Center for the Study of Hate and Extremism at California State University, San Bernardino. “It’s the place where you can come from anywhere and define your own American Dream, and everybody’s got a gripe. The fringes are as hot here as they are anywhere.”

Muslims have borne the brunt of that hate. The SPLC recently claimed that anti-Muslim hate groups nearly tripled in the last year, from 34 in 2015 to 101 in 2016. According to Levin, hate crimes targeting Muslims in California jumped 122 percent between 2014 and 2015, a period that coincided with the San Bernardino terror attack and Donald Trump’s call to ban Muslims from entering the U.S. This past January, someone broke the windows of a mosque in Davis and left bacon at the front door. Several days later, in a radio story about the Muslim ban, Jeff Schwilk of San Diegans for Secure Borders Coalition -- which supports dramatic curbs on immigration and opposed what it called Hillary Clinton’s “mass unvetted Muslim refugee dumping plans” -- told a KQED reporter that “not all Muslims are terrorists, but all terrorists are Muslims.”

On the morning of January 29, in one of his Twitter bursts, Trump wrote: “Christians in the Middle-East have been executed in large numbers. We cannot allow this horror to continue!” Later that evening, Alexandre Bissonnette, a college student and Trump supporter, walked into a Quebec mosque and opened fire during evening prayers, killing six worshipers.

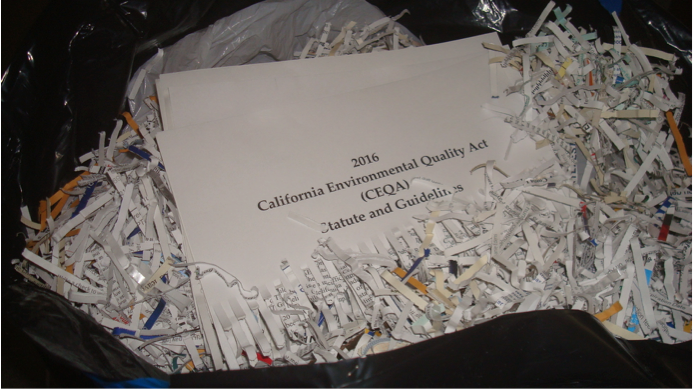

Such developments have Muslims in California on edge. Hamdy Abbass came to the U.S. from Egypt in 1979, and for more than three decades has lived in San Martin, a rural area south of San Jose. For years, he and his fellow worshipers have held services in a converted barn. In 2006 they bought a 16-acre lot with plans to build a mosque. But Abbass has run into fierce opposition from some local residents, led by a group called the Gilroy-Morgan Hill Patriots, whose president is Georgine Scott-Codiga. “They are claiming they are worried about the environmental impact, but that is a smokescreen,” Abbass says. “It’s Islamophobia.”

In an interview, Scott-Codiga tells me that she doesn’t have anything against Muslims, but indeed has concerns about the environmental impact of the proposed mosque. I ask her about her group’s Facebook page, which is filled with links to articles with titles like “The Muslim Plot to Colonize America,” and interviews from a group called Political Islam, identified by the SPLC as an anti-Muslim hate group. Her organization also sponsored a local talk by Peter Friedman, who runs a website called Islamthreat.com -- again, listed as a hate group by SPLC -- entitled “What the Mosque Represents and the Threat of Islam.”

“Well, the people that are committing all of these terrorist acts, they have one thing in common,” she says. “So you have to ask yourself, what’s going on?”

I ask her what is going on.

“Look, it has nothing to do with Islamophobia,” she says, and hangs up.

At a recent community meeting, Abbass tells me, a man warned that the mosque would be used as a base for terrorist attacks. “That was maybe one of the kinder things that was said,” says Abbass. Still, he is undaunted. If all goes as planned, his congregation will begin building the mosque next year. “We have to go with the assumption that we will be targeted,” Abbass says. “But we have to also pray that nothing will happen.”

(Gabriel Thompson is an independent journalist who has written for publications that include the New York Times, Harper's, New York, Slate, and the Nation. His forthcoming book is Chasing the Harvest: Migrant Workers in California Agriculture. This piece was first posted AT Capital & Main.) Klan march photo credit: Los Angeles Public Library Collection. Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

It’s not the story Reggie Borges, a Starbuck’s spokesman in Seattle, wanted to hear after he had just returned from Austin, Texas where his company launched an expansion of its “food share” program this month to Houston and San Antonio.

It’s not the story Reggie Borges, a Starbuck’s spokesman in Seattle, wanted to hear after he had just returned from Austin, Texas where his company launched an expansion of its “food share” program this month to Houston and San Antonio.

The hurdle is that you really need to have every car on the road (and pretty much every other object that can move) under constant centralized control. The buzz word is totally managed systems. Maybe it's a buzz phrase instead of a buzz word, but it carries a heavy load of futuristic thinking. We'll get back to what some of that load entails a little later, but it's worth considering the advantages.

The hurdle is that you really need to have every car on the road (and pretty much every other object that can move) under constant centralized control. The buzz word is totally managed systems. Maybe it's a buzz phrase instead of a buzz word, but it carries a heavy load of futuristic thinking. We'll get back to what some of that load entails a little later, but it's worth considering the advantages.

(Left, undated photo of KKK march, possibly taken in Santa Barbara.)

(Left, undated photo of KKK march, possibly taken in Santa Barbara.)

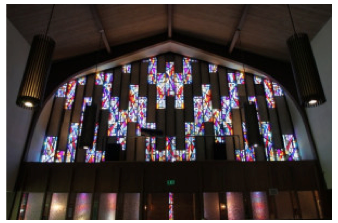

Notably, over fifty-six years earlier, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preached a similar message of unity and inclusion at Woodland Hills Community Church (photo left). Invited to Southern California by a persistent white pastor named Fred Doty who revered King and wouldn’t let the extremely busy and over-extended civil rights leader refuse, King addressed the congregation on his birthday, on January 15, 1961, saying: “Love your neighbor as you love yourself … You are commanded to do that. That is the breadth of life.”

Notably, over fifty-six years earlier, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., preached a similar message of unity and inclusion at Woodland Hills Community Church (photo left). Invited to Southern California by a persistent white pastor named Fred Doty who revered King and wouldn’t let the extremely busy and over-extended civil rights leader refuse, King addressed the congregation on his birthday, on January 15, 1961, saying: “Love your neighbor as you love yourself … You are commanded to do that. That is the breadth of life.”