CommentsAT LENGTH-I mailed the last issue of this newspaper first class, to a long-time subscriber, from the San Pedro Post Office to a San Pedro address, and it took nearly a week to get there.

One might think, “No wonder the USPS is losing money.’’ And it has been a downhill slide for one of the founding departments of our democracy, explicitly authorized by the U.S. Constitution. It was “transformed by the Postal Reorganization Act in 1970 into the United States Postal System as an independent agency” by President Nixon. Later, Congress passed the Postal Accountability and Enhancement Act of 2006, signed into law by President George Bush II.

The U.S. Post Office was historically a government supported agency. In 1970, however, it was forced to become “independent,” and over the years since, as it has been slowly pushed to compete with UPS, FedEx and others, they have watched its revenues decline. In 2006, the Republican-led Congress Accountability and Enhancement Act forced the USPS to pre-pay its future pension by $5.4 billion and $5.8 billion to the Postal Service Retiree Health Benefits Fund from 2007 to liabilities 2016.

This prefunding method is unique to the USPS as most pension funds are on a pay-as-you-go basis that sometimes have surpluses or need to be backfilled, not by billions of dollars out of one budget year.

So what does this have to do with the price of stamps and mail delivery?

In the drive to greater efficiency and to reduce its labor and pension costs the USPS has automated and centralized its mail processing –– eliminating thousands of jobs and even closing some post offices. So the mail that was once processed in your local post office that comes back to that same zip code for delivery, now gets sent to central processing in Los Angeles and shipped back. This takes days and sometimes up to a week. I presume this goes for all the mail dropped at the main post office that’s delivered to P.O. boxes in the very same zip code. I find this incredibly inefficient even though it supposedly saves on labor, which is the point of automation.

The idea that technology is supposed to elevate us from boring repetitive labor while making systems more efficient sounds great, but sometimes those advancements aren’t so efficient or smart. The inefficiencies at the USPS aren’t the fault of workers or management, but are problems cooked up by Congress following a postal strike in 1970.

Congress has been trying to kill the postal service system and privatize it the same way private charter schools are used to bleed public schools of students and resources –– all in the name of making public education “more competitive.” If education could be automated, teachers would become obsolete. Does anyone want a robot math instructor?

On the Waterfront

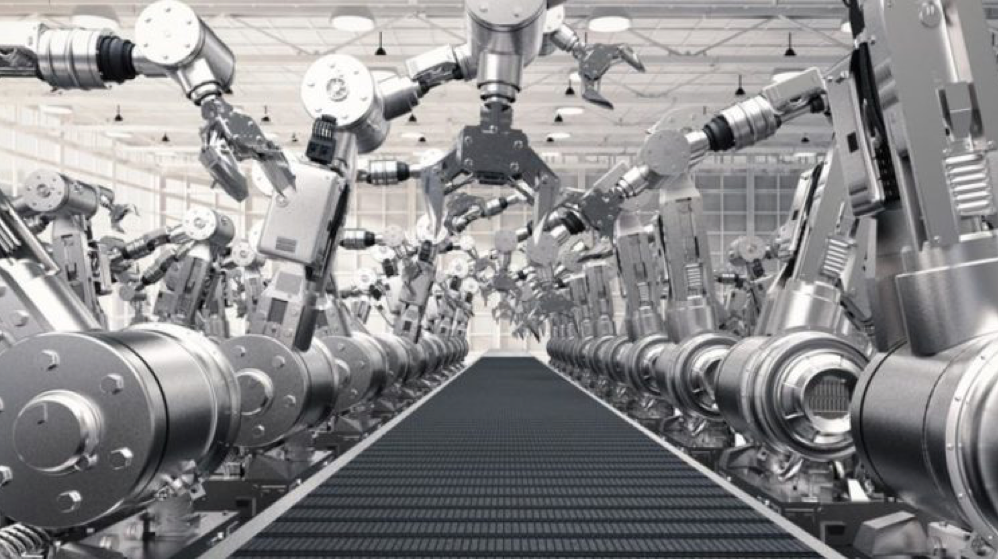

This is also the direction of the global goods movement industry here in the Port of Los Angeles and around the world –– cut labor costs by automating labor in a race to the bottom for the conglomerate shipping companies. This is the true motive behind the APM-Maersk Pier 400 automation, which will not actually increase throughput capacity but is aimed at eliminating jobs and benefits.

This comes at a time when POLA and the Port of Long Beach have both reached record high levels of cargo handling and profits. Of the two automated terminals now operating in the twin harbors it is estimated by some in the ILWU that they are only 75 percent as efficient as the ones fully manned with humans. And the projected growth in this harbor is optimistically focused on the possibility of doubling or tripling in the years ahead.

This seems hard to square with the ports’ own figures of regional job creation and the projections of what automation could mean to the entire logistics/global trade industry or their own projections on growth.

Quite possibly with the evolving “smart” technologies of self-driving vehicles and automated warehouse operations, half the current workforce in Southern California’s global trade could be at risk of applying for jobs as greeters at Walmart or worse, feeding into the ever-growing population of homeless people camped out at the Post Office.

There is really no plan whatsoever for what to do with waterfront workers displaced by automation.

There is an invisible connection between the number of good, middle class jobs on the waterfront and the number of people who end up on the street. There is yet to be an equation calculated between the loss of even 1,000 jobs on our waterfront and its impact on our community in terms of social and economic costs.

There has not yet been one study that projects the economic effects of what automation and job elimination mean to the communities that surround the ports. It’s highly doubtful the tourism industry could absorb or replace even a fraction of those jobs with anything close to the wages and benefits now being paid to dock workers. Yet, these are the twin initiatives now driving the Port of Los Angeles.

For most of humanity, and clearly here in America, we most often define ourselves by the fruits of our labor. Who you are is often defined by what you do for a living. And we have all seen too many examples of cities where the dominant industry has been closed and workers laid off for the very rational excuse of needing to be competitive or lowering production costs by moving production overseas. It has devastated Detroit, Michigan and Youngstown, Ohio. Could the Port of Los Angeles and APM-Maersk be automating themselves into the same conclusion here?

Clearly, POLA has an obligation, not only to the people of the State of California but to the citizens of Los Angeles — especially the ones who live closest to the port –– to be an economic benefit. This cannot be ignored for the sole purpose of benefiting one corporation’s bottom line profits.

(James Preston Allen is the founding publisher of Random Lengths News. Mr. Allen has been involved in community affairs for more than 40 years in the Los Angeles Harbor Area.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.