CommentsCAL MATTERS--Not too many years ago, when California’s government appeared to be totally dysfunctional, some reform-minded folks considered sponsoring a broad overhaul of the state’s governance structure.

However, the reformers, led by the Bay Area Council, a coalition of business and civic groups, ran afoul of one of the state constitution’s most obscure, rarely invoked provisions.

Article 18says that while voters can amend the constitution by initiative, bypassing the Legislature, a “revision” can be placed before voters only by the Legislature or a constitutional revision commission appointed by the Legislature after it asked for and obtained permission from voters to do so.

The sweeping changes envisioned by the reformers would clearly be a revision and they knew the Legislature would never get the ball rolling. Some decades earlier, in fact, voters had approved the appointment of a constitutional revision commission, only to see the Legislature refuse to create one.

Therefore, the reformers tried a two-part approach – an initiative ballot measure to amend the constitution to allow a revision commission to be created via initiative, and a second measure to create such a commission.

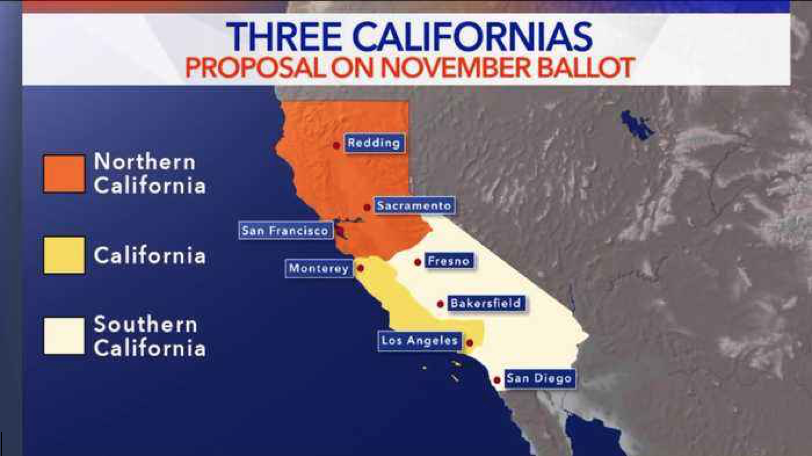

The movement foundered, essentially because of internal conflicts over the scope of the proposed commission’s charter. And now Article 18 has popped up again vis-a-vis an initiative measure placed on the November ballot that would, if passed, set in motion a process to split California into three states.

Proposition 9 is the pet cause of Silicon Valley venture capitalist Tim Draper, and had touched off an international media feeding frenzy. But it faced strong opposition from the state’s political leadership, including both major political parties, labor unions and business groups.

Opponents filed suit, alleging that proposing to split the state would, by definition, be a major revision of the state constitution that Article 18 says can only be initiated by the Legislature, either directly or indirectly.

Last week, while setting aside the basic issue, the state Supreme Court ordered that Proposition 9 be removed from the November ballot “because significant questions have been raised regarding the proposition’s validity, and because we conclude that the potential harm in permitting the measure to remain on the ballot outweighs the potential harm in delaying the proposition to a future election…”

Draper didn’t like it, of course. “Apparently, the insiders are in cahoots and the establishment doesn’t want to find out how many people don’t like the way California is being governed,” Draper said in an email. “Whether you agree or not with this initiative, this is not the way democracies are supposed to work. This kind of corruption is what happens in third world countries.”

Well, no, that’s the way it works when the law is followed as intended.

Draper was trying to bypass Article 18 by making his measure a statute that would command the Legislature to pursue a three-state breakup. The court’s order to delay a vote implies that it sees merit in the opponents’ contention that it would be an unconstitutional revision. But it couldn’t fully explore that issue with an election looming, so it did the sensible thing and put the proposal on hold.

If Draper’s measure passes muster, it will go on the 2020 ballot, but chances are it will fail the constitutional test and be permanently junked – and that’s what should happen.

Splitting California into three new states would be a logistical nightmare and makes no sense except in Draper’s mind.

(Dan Walters writes for CalMatters … where this perspective was first posted.)

-cw