CommentsPERSPECTIVE--Over the past year or so our legislators in Sacramento have let it be known that they aren't happy with the pace of development in California's cities. As housing prices continue to rise, traffic continues to worsen, and the reality of climate change becomes ever more apparent, the Senate and Assembly have decided that local jurisdictions aren't doing their job and that the State needs to intervene.

In 2017 the Legislature worked feverishly to pass bills that would restrict local authority over land use. Now they're starting off 2018 with SB 827, a radical effort to override local planning, claiming it will ease the housing crisis and get more people riding public transit. In reality, it will do neither.

SB 827 is the brainchild of State Senator Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco). It would exempt residential projects that include a percentage of low-income housing from local zoning restrictions if the project is within 1/2 mile of a major transit stop or 1/4 mile of a high-quality transit corridor. This means that local requirements regarding height, density, floor area ratio, and design review would no longer apply. The idea is to promote high-density residential construction along transit corridors. Wiener and many others argue that this would not only ease the housing crisis by producing new units but would also encourage transit ridership, thereby reducing greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

SB 827 is meant to further Transit-Oriented Development (TOD), a policy that state agencies and local jurisdictions have been pushing for years. In theory, TOD seems like a great idea, and the fundamental principle is sound. If you focus residential development along transit corridors it makes access to trains and busses easier, thereby taking cars off the road and cutting GHG emissions. What's not to like?

But there's a big difference between theoretical outcomes and cold, hard reality. The Los Angeles Department of City Planning (DCP) embraced TOD long ago, and invokes it frequently when arguing for high-rise projects anywhere near a transit corridor. So how has that worked out? Not so good. Despite the fact that thousands of new units have been built along LA's transit corridors over the past decade, transit ridership is lower than it was 30 years ago, and it has declined for the past three years running. This is especially disturbing when you realize that LA County (the area served by the MTA) has added over one million residents during that same period. It's not just that transit ridership hasn't increased, it hasn't even kept pace with population growth.

Don't take my word for it. Check out the recent report released by UCLA's Institute of Transportation Studies, "Transit Ridership Trends in the SCAG Region.” (SCAG stands for Southern California Association of Governments.)

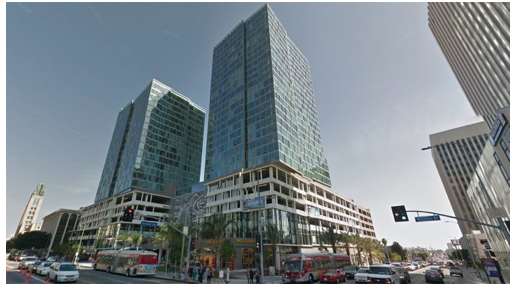

While the report covers all of Southern California, the data show that LA is leading the region in lost transit ridership. So as City Hall approves one skyscraper after another, making the claim that TOD will save us all, the number of people actually taking busses and trains has plummeted.

The report provides much valuable insight into what's happening on the transit landscape. While local and regional officials have enthusiastically promoted large scale development, claiming that these projects are transit friendly and will reduce traffic, in reality, per capita vehicle ownership in the SCAG region has risen dramatically since 2000. During the 1990s the region added 1.8 million people and 456,000 household vehicles, or 0.25 vehicles for every new resident. But from 2000 to 2015 the region added 2.3 million people and 2.1 million household vehicles, or 0.95 vehicles per new resident.

But that's just Southern California. Maybe things are going better up north? Not really. With the fervent support of Bay Area officials, developers have been having a field day in San Francisco and beyond, building thousands of new units and claiming the increased density will boost transit ridership. But here's a quote from Vital Signs, a web site maintained by regional agencies which provides info on Bay Area transit:

"While featuring one of the nation’s most extensive public transit systems, the Bay Area has not experienced significant growth in transit ridership over the past few decades – with residents primarily shifting between bus and rail modes. This has resulted in crowded conditions on BART and Caltrain, while suburban buses have lower utilization than in years past."

The site highlights the fact that per capita transit ridership in the Bay Area has declined by 11% since 1991. And while many have touted the fact that an increasing number of San Francisco households are car free, that doesn't mean people aren't using cars. A recent report from the San Francisco County Transportation Authority showed that people are making 170,000 trips via Uber and Lyft on weekdays. This amounts to 570,000 vehicle miles driven by Uber and Lyft cars on a typical weekday. Bottom line, in spite of all the TOD boosterism by San Francisco officials, lots of people are still using cars to get around.

So while state and local officials have been telling us for years that that high-density development will get people out of cars and onto transit, that hasn't happened. But what about housing? Even if SB 827 might not deliver on transit ridership, wouldn't it still ease the housing crisis by generating lots of new units?

We do need to build housing, but creating new units isn't going to ease the crisis unless they're accessible to middle-income and low-income Californians. While SB 827 makes the inclusion of affordable units one of the criteria for removing restrictions, the percentage of affordable units isn't likely to make a significant difference. Generally, density bonus incentives are offered on projects that include between 10% and 20% affordable housing. This means that the rest of the units are "market rate" (i.e. really expensive) and most likely to attract the demographic that owns and drives cars.

To make things even worse, research is showing that new development along transit corridors has been causing gentrification and displacement. The Urban Displacement Project, a joint effort by UCLA and UC Berkeley, recently released a gentrification map of LA. This research shows that high-density development near transit lines has pushed housing costs up and pushed low-income residents out of Chinatown, Highland Park, East LA and Hollywood. And anyone following the LA real estate scene knows that as soon as the MTA's Crenshaw/LAX Line was approved investors started diving into communities like Leimert Park and Inglewood. The result? More gentrification and displacement.

Putting all this together, it's hard to see how SB 827 will deliver any benefits either in terms of housing or transit ridership. And it's important to be specific about the reason why. It's not that TOD is a bad idea in itself. The problem is that despite all the talk, state and local policy has not been geared towards producing new housing that will increase transit ridership. In reality, what local governments have been doing is using the TOD argument to promote unchecked development.

In LA, City Hall has been shredding local zoning and offering developers generous entitlements while arguing that this will ease the housing crisis and promote transit ridership. The DCP has been telling us that they're planning for a new TOD era where people won't need cars. But what they've actually produced is a tangle of new planning initiatives, none of which mean anything because the City Council will sweep aside any zoning regulations in place for developers that have enough clout at City Hall. And the bottom line is that housing costs continue to rise while transit ridership continues to fall.

SB 827 will only exacerbate the situation. In cities across California we're seeing high housing costs, homelessness, worsening congestion, and declining transit ridership. The only way to solve these problems is through real planning. Creating plans that truly serve the needs of our urban communities is difficult, complex work. It means starting with hard facts rather than wishful thinking. It means doing neighborhood outreach instead of backroom deals. And it means engaging with communities in long, difficult discussions where all stakeholders have a chance to be heard.

The folks in Sacramento want us to believe we can forget about doing the hard work that planning demands and solve our problems with a quick and easy shortcut. Don't believe it. SB 827 will not solve the housing crisis or get more people on transit. It will only continue to fuel the speculative development binge that's crippling California's cities.

If you have a problem with Sacramento overriding local planning control, better contact your representatives in the State Senate and Assembly quickly. If last year's legislative session is any indication, developers and their lobbyists will be pushing hard for the passage of this bill. And it couldn't hurt to also call your local city officials to tell them you oppose SB 827. There's only one way for California to solve its problems, and that's through real planning. There are no shortcuts.

(Casey Maddren is a native Angeleno, and currently serves as president of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (www.un4la.com). He also blogs about the city at The Horizon and the Skyline.) Edited for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.