CommentsPLATKIN ON PLANNING--Several times a year my wife and I bike from the Miracle Mile area to Venice Beach. Moving through Los Angeles on a bicycle reveals much more that than barely seeing a blurred cityscape from an enclosed, faster-moving car.

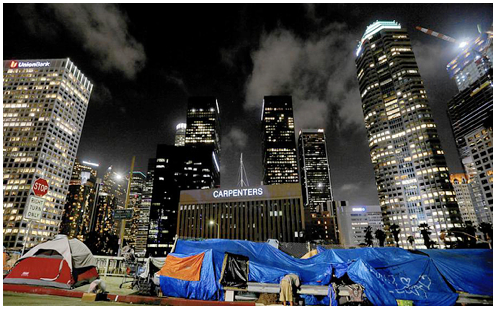

These are my impressions from a late December bike ride to the beach. What we saw is not pretty. In Los Angeles we are living in a modern Tale of Two Cities. It is not London versus Paris, like Charles Dickens wrote in 1859, but the haves and the have-nots, with fewer people in between.

Homeless people everywhere. In the past we saw occasional homeless people, but this time, there were many homeless people and homeless encampments along the entire route. This is fully consistent with what people tell me from every corner of Los Angeles, from the wealthiest to the poorest communities.

While City Hall gives us wonderful words and negligible housing programs, the economic and social engines responsible for homelessness and homeless encampments are churning full blast in Los Angeles.

New building sites. While the homeless population and homeless encampments are rapidly growing, so, too, are new building sites, one of the most insidious causes of their plight. It is now hard to find a neighborhood in Los Angeles where developers have not recently demolished older structures, often houses and apartment buildings. This is all a prelude to new, in-fill commercial buildings, many with expensive apartments or condos. As for the local homeless, all they can do is sleep on the outside, wondering what is going on behind those pristine locked doors and windows.

So far this building boom only demonstrates the following:

- There is no shortage of speculative investment capital flowing into Los Angeles real estate.

- There is no shortage of infill locations for these new real estate projects.

- There is no shortage of City Hall assistance for these projects.

- There is no way that Los Angeles can build its way out of a housing crisis through this private investment, even if it is occasionally infused with a dash of public sector support.

Haphazard and decaying infrastructure. On a bicycle you quickly learn how to avoid cracks and potholes on LA’s streets, many of which are in awful shape. You also discover that LA’s bicycle infrastructure is woefully deficient. Even though sunny Los Angeles has 6,500 miles of streets, many flat and wide, it only has about 350 miles of bicycle lanes, most fading white lines once painted on a city street. In one case we found a mile of new, well-marked bicycle lanes on Venice Boulevard, but never came across a grade-separated bicycle lane. There is no mystery on how to build these truly safe bicycle lanes, since they are already the norm in New York City and Chicago, despite their wind, rain, and snow.

Appalling Urban Forest. Even though Los Angeles does not have an urban forest management plan, much less a General Plan Urban Forest Element, there are still a few neighborhoods, like Holmby Hills and Hancock Park, with an admirable street trees. Otherwise, in LA’s 500 square miles, a few wide streets have large boulevard trees that have been properly planted and pruned. But these are the exception. Many wide streets only have tiny trees, often Crepe Myrtles that are totally inappropriate in scale.

These streets, with their stunted trees, might be the lucky ones, however, because many Los Angeles boulevards and neighborhoods streets are either treeless or planted with a scattered, hodge-podge of different tree species. While this is marginally better than totally treeless vistas, nearby cities, like Beverly Hills and Culver City, demonstrate that you can have it all. They have a wide variety of carefully selected street tree species that they have properly planted in the entire city, and then properly maintained. These cities have the same climate as Los Angeles, are suffering from the same development threats, long-term drought, and new tree insect pests and diseases, yet look remarkably better.

What is their secret to a successful urban forest that is standing up to the same threats? It is a question of priorities! Their elected officials decided to spend money on expertise, materials, and sufficient staffing to overcome these new hazards.

Climate Change is literally in the air. Even though late December has had clear, crisp days, California’s largest wild fire on record – the Thomas Fire -- is still burning. All predictions are that a year-round fire season is the new normal for California. Our ongoing mega-drought, in which Los Angeles has so far had only .1 inch of rain since last spring, also aggravates the long-term danger of wildfires.

Furthermore, for trees and chaparral that depend on natural precipitation, not irrigation like their urban cousins, their future is dire. According to the Los Angeles Times, there is already a massive die off of riparian trees and chaparral in the Santa Monica Mountains. Assuming that severe droughts are here to stay and will be worsened by heat waves, we should expect dramatic changes in Southern California’s flora. After droughts and fires ravage the landscape, invasive species, usually grasses, take over former woodlands, making it difficult for native trees to ever return, even in wet years.

We also know from a parade of new climate studies, that climate change is accelerating. In fact, it is already visible over the entire planet, including Los Angeles, where it will certainly get much worse. Unlike the Trump administration, though, we have elected officials at both LA’s City Hall and Sacramento who are not professed climate change denialists. But, beyond words and token actions, there is little to differentiate them from the White House. In Sacramento they continually target the California Environmental Quality Act and propose ever more insidious ways for real estate speculators to evade environmental reviews.

Meanwhile, at our own City Hall, every alarming environmental finding for a new real estate project is whisked away through the City Council’s unanimous Statements of Overriding Considerations. At the same time any serious effort to plan and then monitor climate change mitigation in Los Angeles is pushed further into the future under the catchall category of Resilience. In fact, the on-line outline for the eventual Los Angeles General Plan update only mentions adapting to climate change, not mitigating its causes. In other words, the City of LA’s official planning process has yet to detail any programs, including a companion monitoring process, that reduce the local generation of the Green House Gases responsible for climate change. While many potential mitigation programs are buried in older planning documents, they have not and will not be updated and integrated into a unifying Climate Change element. Likewise, there is no process at City Hall to monitor climate change in Los Angeles and then determine the role of each City department to reduce our individual and collective carbon footprint. There is a word to describe this negligence: ho-hum.

A Way Out: What sense can we make of this catalog of doom and gloom, and how can we find a way out? None of what we observed on our bike ride is inevitable, and there are many ways that LA could respond, but so far, has not. In fact, by inaction and bad choices, City Hall has actually made LA’s overall situation worse, not better.

This is because there is a common denominator linking the many “separate” crises described above. It is treating Los Angeles, including its many neighborhoods, its thousands of real estate parcels and its infrastructure as commodities. They are only things to be bought, sold, or invested into. While market economies continually boom and bust, there is no reason why they need to drag cities like Los Angeles up and down with them. What Los Angeles really needs to become is a buffer against this economic turbulence, not an institution that blows oxygen on the glowing embers of real estate speculation during booms, and then nearly shuts down during busts.

Furthermore, the city’s support for this helter-skelter economic dynamo builds on itself. This is why, according University of Oregon environmental researcher, John Bellamy Foster, climate change is accelerating. He argues that the market system’s ever expanding pool of investment capital directly leads to faster rates of climate change. As economies expand – with a public assist -- the amount of carbon they extract from the earth and then pump into the air closely follows. Quite simply, Foster explains how what is praised as growth directly leads to adverse climate impacts. This is also why Foster and other writers, like Richard Smith, argue that green capitalism -- economic expansion without increased carbon pollution -- remains a myth. In a word, producing and consuming more “green” products is not a solution to climate change, it quickly become part of the climate problem.

But cities like LA do not need to be a prisoner to this process. While they are not likely to overhaul the economic system, they can carefully measure the carbon impacts of all new projects, public and private, and then approve the environmentally superior feasible alternatives. It is their political choice.

Likewise, they can choose to house the homeless and plant and maintain a proper urban forest, one of the best forms of climate change mitigation and adaptation available. The same City Hall decision-making process applies to LA’s non-automobile transportation infrastructure, especially sidewalks and bike lanes. In all of these cases, there is an economic basis to the decisions. This means we know where the buck stops, whether it is homeless encampments, decaying infrastructure, emaciated urban trees, or energy and resource-intensive speculative real estate projects.

The time for accountability is at hand.

(Dick Platkin is a former LA city planner who reports on local planning controversies for CityWatchLA. Please send any comments or corrections to [email protected].) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

-cw