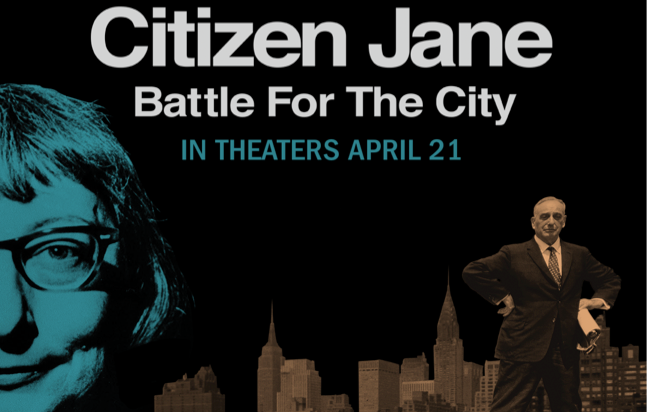

CommentsPLATKIN ON PLANNING-I recently saw the new documentary about Jane Jacobs, called Citizen Jane: Battle for the City. Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times praised it to the heavens, but my take is more muted.

The film’s history of New York City in the immediate post-WW II era clearly offers some valuable lessons for LA’s endless city planning disputes. In New York the vision of Robert Moses, the City’s construction czar, prevailed through the 1960s. It was based on the top-down rebuilding of New York City inspired by the modernist vision of Swiss architect, Le Corbusier. As applied to New York and other major cities, including Los Angeles, this approach lead to widespread urban renewal projects based on three planning principles: automobiles, freeways, and high rise buildings. In New York the new high-rise buildings took the form of public housing complexes built through well-intentioned slum clearance projects.

This top down planning model eventually collided with the bottoms-up vision of professional writer and neighborhood activist, Jane Jacobs. Through her many articles, widely read books, and community organizing, she lead grass roots campaigns in the 1950s and 1960s that stopped several of Moses’ later rebuilding projects, most notably the Lower Manhattan Expressway. Her successes then inspired similar efforts to block new urban freeway projects and high-rise housing projects in many other U.S. and Canadian cities.

Useful Lessons from this documentary:

Lesson 1) Public and private projects should serve the needs of local residents and organic communities. Meeting broad public goals by destroying local communities through top-down redevelopment and transportation projects seldom works and must be opposed.

Lesson 2) Despite the extraordinary power of elected officials and developers, the public can successfully organize to block truly awful top-down projects and replace them with their own bottoms-up vision. It is not easy, but even in Los Angeles there have been notable successes, such as the long-forgotten Beverly Hills Freeway. If built, it would have would have replaced Santa Monica Boulevard and Melrose Avenue with a new freeway linking the I-405 to the 101. First proposed in the early 1940s, official maps finally erased this freeway in 1975 after several decades of well-organized west-side opposition.

But, despite these useful lessons, this documentary also needs some serious updating. This Jane Jacobs story stopped in the early 1970s, when most freeway and public housing construction ground to a halt. But, coincidence is not cause, and those private economic interests that supported and handsomely benefited from Robert Moses’ massive projects never threw in the towel. They quickly adapted their business models to new urban realities. Decades later, they still harbor top-down grandiose visions for rebuilding American cities, like Los Angeles, through an alliance of their companies with local officials.

To begin, the Vietnam War, just as much as local political opposition inspired by Jane Jacobs, led to the demise of large public housing buildings and most new freeway projects. In the 1960s President Lyndon Johnson (LBJ) claimed he could fight the Vietnam War without domestic cutting backs. He called his approach, “Guns and Butter.” But, LBJ was wrong. The guns won, the butter lost; and the subsequent Nixon administration unleashed public housing cutbacks that continue nearly 50 years later.

Instead of replacing large, high-rise super-blocks of public housing with low-rise townhouses, Congress and the White House simply eliminated most public housing programs. This is why we are now left with such weak affordable housing band-aids as density bonuses, inclusionary housing, and a corrupt Federal affordable housing tax credit program. Now in its fifth decade, the elimination of these public housing programs spawned more backroom deals, relocation to distant suburbs, inner city overcrowding, and mass homelessness. These are hardly victories that Jane Jacobs would have celebrated.

As for freeway construction, budget constraints also killed most new projects, and now most states, like California, are struggling to maintain an Interstate Highway System begun in 1956 to defend the United States from the Russkies. No kidding!

While a few over-priced freeway projects still squeak through, like the $1.4 billion project to widen the still gridlocked I-405 between the Santa Monica and Ventura Freeways, that big-ticket era is now over. And, at this point it will take far more than another Cold War, even with cheerleading by MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow, to reignite a second freeway building frenzy.

But, real estate developers and their ever-faithful City Hall and State House enablers have fully reinvented themselves since the 1970s. Of course, they still hope to make piles of quick profits, but instead of government contracts to build freeways, they clamor for public works projects to build light and heavy rail. Plus, instead of “donations” to elected officials for contracts to build public housing, they have turned their attention to pay-to-play spot-zones and plan amendments for high-rise luxury housing and shopping centers. Sometimes, for good PR or an extra discretionary approval, the developers will add a few affordable apartments into the mix. But, since the pols then make sure there will never be on-site inspections of these affordable units, the developers are free to increase their rents to market rates.

As a result, developers can still demolish old buildings and then displace local residents to make way for new tenants. The difference from the Jane Jacobs era is that their business model no longer depends on urban renewal projects, freeways, and high-rise public housing projects. They can get to the same place through piece-meal, pay-to-play soft corruption to build private, market rate developments. It is more labor intensive, but they almost always finish the race, especially when they claim (without a shred of evidence) that their real estate projects are transit-oriented. But, just like the mega-projects of the Moses-Jacobs era, the new mega-projects are still automobile-oriented despite the endless hype about transit. Whether new luxury apartments, office buildings, or shopping centers, nearly all employees, residents, and shoppers drive to these destinations, even when they happen to be near mass transit.

Why was such important information excluded from this film?

The documentary’s opening credits identify the film’s underwriters: The Ford Foundation and the Rockefeller Foundation. Both foundations have a long, well-documented history of urban projects that selectively support handpicked activists. If they focus on community and then steer their activism away from exposes of collusion and corruption between large real estate investors and public officials, local groups apparently pass the threshold for major foundation funding.

How did the Robert Moses approach, vilified in the documentary, appear in Los Angeles?

Los Angeles had two famous slum clearance projects, and one actually resulted in some new, high-rise replacement housing.

Bunker Hill, which can still be seen in many classic film noir movies set in Los Angeles, was on the western edge of the downtown. Through the Bunker Hill urban renewal project, the original Victorian houses, their residents, and some hills were removed, replaced by the Harbor Freeway and the high-rise, pedestrian-free, car-oriented hotels and banks on Flower and Figueroa Streets. But, at least the Angelus Plaza high-rise public housing complex for seniors was folded into this urban renewal project. Unlike the Moses style high-rise public housing projects that were total failures, the public housing on Bunker Hill is doing just fine after 37 years of continuous operation. Nevertheless, to avoid street level pedestrian activity, the CRA proposed an underground and elevated People Mover transit system to the tune of about $300 million. Killed by the Reagan Administration in 1981, in current dollars it would have cost over $1 billion.

Chavez Ravine is the most infamous LA slum clearance project. Under the leadership of Frank Wilkinson, Special Assistant to the Director of the Los Angeles Housing Authority, this old Mexican-American community was supposed to make way for well-designed new public housing through a slum clearance project. Called Elysian Park Heights, the famous Austrian-American architect Richard Neutra completed detailed designs. His online renderings reveal that it would have included many two-story buildings, mid-rise residential towers, and substantial landscaping. In fact, it would have resembled another Le Corbusier-inspired residential project in Los Angeles, Park LaBrea.

The first step met with substantial local resistance, but eventually the Los Angeles Housing Authority moved out all local residents. But, the next step, Neutra-designed public housing, never appeared. Instead, Wilkinson and other Housing Authority officials were fired because of their presumed Communist Party affiliations. Once pushed out of the way, the Los Angeles City Council quickly handed over the emptied Chavez Ravine to Walter O’Malley so he could build a stadium for the recently relocated Brooklyn Dodgers.

Today’s reality. By 2017, slum clearance projects and new freeways have become a thing of the past in Los Angeles. Instead, the private market, in cahoots with public officials, gradually forces out low and middle income residents through a variety of gentrifying programs. These include mansionization, cash-for-key evictions, Ellis Act evictions, Small Lot Subdivisons, and deliberate negligence that makes apartments so unlivable that tenants leave on their own.

But, no matter how residents are legally or illegally evicted, the next step is similar. In-fill replacement housing caters to the well-off, while nearly all of the evicted double up, live in cars and the streets, head off to much cheaper cities, or reluctantly move to distant suburbs. If they luck out, they find affordable apartments, but they still must tolerate long commutes, strangers in lieu of neighbors, and a low-amenity environment.

(Dick Platkin is a former Los Angeles City Planner who reports on local planning issues for CityWatcLA. Please send any comments or corrections to [email protected].) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

21

Sat, Feb