CommentsPOLITICS-On Oct. 6, 2018, Brett Kavanaugh was confirmed to the U.S. Supreme Court by the narrowest of margins, with 50 votes in favor and 48 votes against.

He is the first justice in U.S. history to be confirmed by senators representing less than half of the country (44 percent), with a majority of the population (52 percent) opposed to his nomination.

Kavanaugh is the second Supreme Court justice picked by President Donald Trump. Trump, in turn, is the second president in five elections to enter the White House after losing the popular vote. In 2000, George W. Bush lost the popular vote to Al Gore by 540,520 votes but won the Electoral College after the Supreme Court halted the Florida recount. Similarly, Trump lost the popular vote to Hillary Clinton by an overwhelming 2,809,197 votes. But like Bush, Trump won the Electoral College, and thus the presidency.

The U.S. political system is institutionally rigged in favor of conservative white voters who drastically diverge from the political values of most Americans. This is why Kavanaugh was able to be confirmed by the Senate, and it’s the reason filmmaker Michael Moore, who predicted Trump’s victory in 2016, recently warned that Trump could very likely be a two-term president.

Unless voters organize to amend the Electoral College, our Constitution will continue to be one that treats citizens of color as less than whole people.

I am a scholar of migration, which wouldn’t seem to be related to the U.S. electoral system at all. However, a close look at demographic shifts in the United States over the 20th century helps us understand just how rigged America’s government is, how Trump became president and why it’s more likely than not that he’ll be re-elected in 2020.

Supporters of the Electoral College argue that the system insulates the executive branch from the whims of an uninformed public and balances power between sparsely populated rural states and densely populated urban states. As benign as this arrangement may seem, however, it’s steeped in the legacy of slavery, discrimination and racism. In practice, it systematically undervalues minority voters in urban areas in favor of white voters from rural counties.

At the 1787 Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, representatives from Southern states feared their residents would be at a disadvantage vis-à-vis those of Northern states because fewer voting-eligible citizens lived in the South. This led to the infamous three-fifths compromise, which allowed Southern states to count each enslaved person as three-fifths of a citizen and thereby increased Southern representation in the House.

A separate compromise ensured that each state, regardless of population, had two senators. In other words, the structures of both the House and the Senate were concessions, motivated by practicality rather than principle, made to get Southern states to sign onto the Constitution. The whole thing was at an impasse without them and the result was that Southern states left the negotiating table with 33 percent more representatives in Congress than if slaves had been ignored.

Because each state gets as many votes in the Electoral College as they have in the House and Senate combined, the two-senators-per-state rule gives less-populated states disproportionate power in presidential elections.

While the three-fifths arrangement has been eliminated, the original configuration of the Electoral College maintains that deep imbalance between rural states and urban states, which now systematically favors white voters.

Here’s why.

In the 20th century, millions of Americans left the countryside for the city. One of the biggest shifts involved the millions of black people who left the South between 1916 and 1970. According to the U.S. Census, at the turn of the 20th century, 90 percent of black Americans lived in rural Southern states, but by 1970, less than 50 percent did. Most hoped to settle where they could sit in the front of the bus, go to school, access credit to buy houses or start businesses, and vote. In short, they left for more progressive, and typically urban, areas in the North.

A close look at demographic shifts in the United States over the 20th century helps us understand just how rigged America’s government is.

Similarly, following the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, many Native Americans began to leave their nations in search of work and more stable social conditions in cities. Asian-Americans, many of whom had lost their land to the government and opportunists during World War II, also relocated to urban areas.

Hispanic ranchers and farmers faced a similar fate. Struggling to access loans for their farms and ranches, they left in droves for the cities too. They had no choice.

The mass exodus of minorities out of rural areas should have penalized rural states by reducing their share of electoral votes. But because of the two-senators rule, the Electoral College now grossly overvalues voters in rural, less-populated states. And while many white voters have left rural areas as well, minorities as a group were much more impacted by rural-urban migration flows.

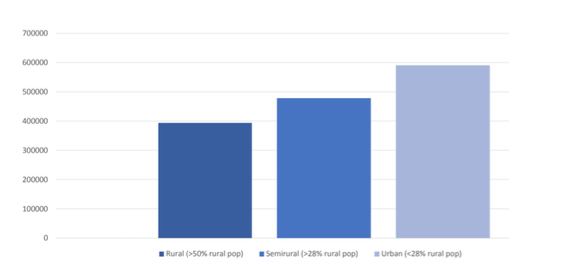

As Graph 1 shows, rural states in 2016 had one electoral vote for every 393,293 residents, whereas urban states had one electoral vote for every 590,081 residents. According to the 2016 American Community Survey, 81 percent of residents in rural states were white, compared with 75 percent in semi-rural states and only 57 percent in urban states.

Population per Electoral Vote in Rural, Semi-rural and Urban States

Benjamin Waddell Data comes from the 2016 American Community Survey.

The three groups that most heavily support Democratic candidates — blacks (88 percent for Clinton in 2016), Hispanics (66 percent for Clinton) and Asians (65 percent for Clinton) — now find themselves disproportionately living in densely populated states whose electoral votes are undervalued compared to those rural, less-populated states.

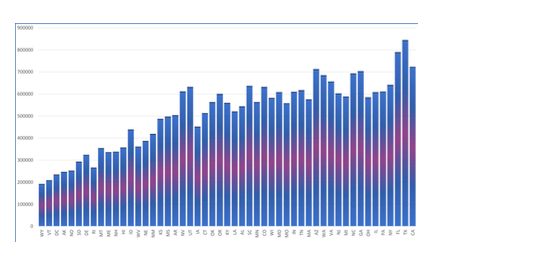

As Graph 2 shows, in the 2016 election, Wyoming — where 84 percent of the population is white ― had one electoral vote for every 187,875 residents. California — where 62 percent of the population are minorities ― had one electoral vote for every 677,344 residents. So, if a person moved from Wyoming to California, their vote would lose nearly 66 percent of its value in presidential elections.

Population per Electoral Vote

Waddell Data

The Electoral College was designed to buttress the power of white rural voters, and true to that purpose, it continues to suppress the power of minority voters today. Critics may argue that Hillary Clinton lost because she failed to round up as many voters in 2016 as Barack Obama did in 2008 and 2012. But Clinton didn’t so much lose the national election as she failed to win enough support in several states stacked with white voters.

Clinton handily won California (62 percent minority) and New York (43.5 percent minority), barely lost Florida (42.2 percent minority), and racked up more votes in Texas (56.5 percent minority) than Obama had. Together, these four states account for 33 percent of the nation’s population and an increasingly larger percentage of the nation’s minorities. However, Clinton lost traction in Michigan (75 percent white), Pennsylvania (78 percent white), Ohio (80 percent white) and Wisconsin (82 percent white), and as a result, she lost the election.

What this all adds up to is a rather unpopular but quite sound prediction: Donald Trump is likely to win a second term.

And unless voters organize to amend the Electoral College and the Senate — or abolish electoral votes altogether — our Constitution will continue to be one that treats citizens of color as less than whole people.

Fortunately, the type of social pressure necessary to restructure the rules of the game may not be that far off. Diversity is on the rise in rural America, and while these populations are young, within the next decade minorities will emerge as a powerful voting block in many rural counties across the country. At that point, the future of the nation will rest in the hands of ethnic and racial minorities for the first time in U.S. history.

(Dr. Benjamin Waddell is an associate professor of sociology at Fort Lewis College in Durango, Colorado. He spent the last two years living in Managua, Nicaragua, where he researched matters related to development, international migration and crime. This piece first appeared in HuffPost.) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.