CommentsGUEST WORDS--Ben Montgomery and a team from the Tampa Bay Times asked 400 law enforcement agencies across Florida for records of when an officer fired a gun and injured or killed someone between Jan. 1, 2009 to Dec. 31, 2014. The shooting of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri prompted questions about how often such shootings happen. The result of the inquiry is an extensive report titled "Why Cops Shoot."

"It was very difficult to get agencies to cough up records," Montgomery says in a video accompanying the story. Collecting the information took two years. Their mission was to answer a basic question: "Are there ways to do this where people don't have to die?"

The Tampa Bay Times report arrives even as Attorney General Jeff Sessions announced in a March 31 memo that his office would call a 90-day pause in its consideration of police reform efforts begun under the Obama administration.In Baltimore last night, U.S. District Judge James K. Bredar issued an order rejecting the attempt by Sessions and the Trump administration to delay public consideration today of the consent decree between the Department of Justice and the Baltimore police department. Bednar's writes in the order, "To postpone the public hearing at the eleventh hour would be to unduly burden and inconvenience the Court, the other parties, and, most importantly, the public." The hearing is scheduled for 9:30 a.m. EDT.

The Sessions memo recommends that the "misdeeds of individual bad actors" not "impugn or undermine the legitimate and honorable work" of law enforcement. Yet the Tampa Bay Times report uncovers yet again patterns of policing that result in unnecessary deaths of citizens — many unarmed — and community mistrust of police services. Too many police shootings are “lawful, but awful” according to Chuck Wexler, Executive Director of the Police Executive Research Forum (PERF).

This is one such example from "Why Cops Shoot":In January 2010, Orange County sheriff's deputies moved in on Torey Breedlove, a suspected car thief in an SUV. Breedlove tried to drive away but was surrounded by deputies with guns drawn. A witness said Breedlove raised his hands, but deputies said they heard an engine revving, so they fired 137 rounds, killing Breedlove. A grand jury cleared the deputies, but Breedlove's sister sued on behalf of the man’s four children. Evidence presented in the civil case showed the revving engine was a deputy's SUV, not Breedlove’s. His sister got $450,000.

“The conduct at issue here,” wrote U.S. District Judge Gregory A. Presnell, “is more akin to an execution than an attempt to arrest an unarmed suspect.”Montgomery is circumspect. "There are not any incidents that we looked at in these 770 cases, in which 830 people were shot," Montgomery says, "which clearly spell out that this officer intended to murder someone. That's not the case at all as far as we could find. What is the case are, in some cases, lack of training, just the rush to judgment."

And simply bad practice.In 2014, for the first time ever, police took more from American citizens than burglars did, according to economist Martin Armstrong, who used statistics from the FBI and Institute for Justice. Police departments use the money, cars and homes seized through civil asset forfeiture to support their budgets.

“The answer to the riddle of why officers who are assigned to drug and gun and other contraband-oriented assignments, who are armed to the teeth, often in military fashion, take the time and trouble to make traffic stops for mundane offenses like ‘tag light out’ or ‘no seat-belt’ can be answered by the multi-million dollar forfeiture trade that supplements police incomes,” Cook said.Mike Chitwood, now sheriff of Volusia County, was police chief in Daytona when Montgomery interviewed him. Chitwood believes the key to the use of force is proportionality. He has been engaged for years in Wexler's group and brought training in deescalation and active listening to Daytona:

“We’re proficient in (shooting), but we’re not proficient in the No. 1 thing: dealing with people,” he said. “I think the No. 1 complaint in America against police officers is rudeness.”

He also began to try to keep crooked cops out of his department by hiring people with solid, deep background investigations. He established an alert system to try to identify rogue cops. He started randomly drug testing officers.

[...]

What’s particularly interesting about Chitwood is the stricture of his policies, especially when it comes to police chases and use of force. He’s blunt. Don’t shoot into a vehicle. If you do shoot, he said, you’d better have tire tracks on your chest.

“I think most shootings that we see are because we the police put ourselves in a position that we don’t need to be in,” he said. “Today, for some reason, we’ve switched out of the guardian mentality and we’ve become warriors. And that’s not what American policing was founded on.”We've looked at the "warrior cop" here before.

One might not blame an incoming administration for stopping to review the policies of its predecessor. Then again, people are dying. "Why Cops Shoot" gives an indication of why and what might be done about it in addition to creating a national police violence database for studying it.Montgomery concludes we need one. The question this morning is whether Jeff Sessions and the Trump administration are more interested in American policing being tough or just. Wait, don't answer that.

"We're the only country in the world that polices like this," Chitwood says.

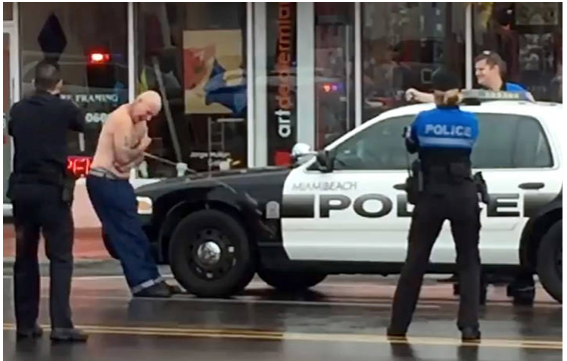

(Tom Sullivan is a North Carolina-based writer who posts at Hullabaloo and Scrutiny Hooligans. A former columnist for the Asheville Citizen-Times, his posts have appeared at Crooks and Liars, Campaign for America's Future, Truthout.org, AlterNet, and TomPaine.org.) Photo by Kate Sheets via Creative Commons.-cw

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

11

Wed, Feb