CommentsELECTION PENDULUM--Americans love to argue about the rules of picking major party presidential nominees. But no matter the method, these contests are essentially the same: They pit party elites against the voters.

There is a clear pattern, a back and forth, that my co-authors and I identified in researching for our book, The Party Decides. While rule changes may give the upper hand to voters for a few presidential cycles, elites will always try to find ways to stage this voting process in their favor.

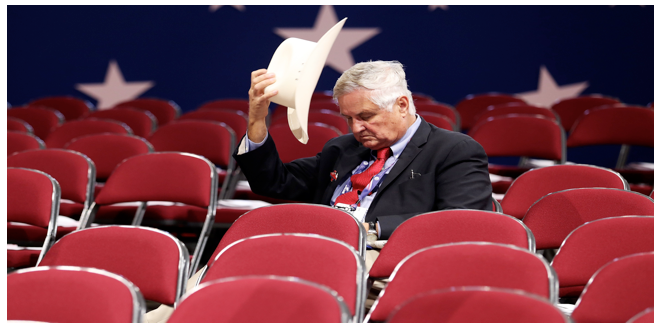

At this summer’s conventions, both parties are reconsidering the rules of the presidential selection process, after Donald Trump’s divisive triumph on the Republican side and Bernie Sanders’ strong Democratic challenge raised questions about the fairness of procedures. But no matter what reforms to the selection process that parties may pursue, the back-and-forth struggle between elites and the voters will likely continue.

Today, the nominating process is itself the product of reforms that didn’t alter this dynamic. Presidential elections now consist of both primaries—where residents simply cast their ballots in the area designated to them based off their address—and caucuses—where voters gather openly to decide which candidate to support.

This mix of primaries and caucuses is relatively new to American politics.

In the early decades of the Republic, members of Congress got together to decide presidential nominations. The rest of the nation was totally frozen out of the process. In the early 19th century, reforms designed to make the process more representative led to national party conventions. These gatherings enabled leaders from across the country to take part in the momentous decision of nominating a potential president. The convention system lasted for more than a century until there was a reform movement put in place to increase participation even further.

The modern presidential nominating process wasn’t born until 1968. The Democratic Party—like the rest of the country—was deeply and sharply divided over the war in Vietnam, when party leaders meeting at the convention in Chicago decided to select the sitting vice president, Hubert Humphrey, to take on Richard Nixon in November. There was rioting in the streets and shouting in the convention hall. The problem was not just that Humphrey was intimately associated with the Johnson administration’s hawkish military policies in Southeast Asia. What drew the ire of many was that Humphrey had failed to compete in any of the primaries and caucuses that nominating season. He was plucked from the wings and foisted upon the party in a very undemocratic fashion.

In 1968, this type of political movement could occur because primaries and caucuses were not binding. In the aftermath of that bitter convention, Democrats created the McGovern-Fraser Commission to democratize the nominating process. They decided that, starting in 1972, candidates who won the most votes in each contest would receive the most delegates from that state, conferring significantly more importance on the primaries and caucuses. Additionally, the candidate who amassed a majority of delegates—2,383 for Democrats and 1,237 for Republicans—would automatically become the party’s nominee. While McGovern-Fraser was a Democratic Party committee, Republicans followed suit and the two parties had in place extremely similar procedures by 1976.

… if your preferred candidate is ultimately victorious, the complaints tend to be muted. But supporters of the losing candidates are often quite vocal in their disparagement of the system—and 2016 was no different …

The goal was to wrest the power to nominate away from the party bosses and give it to the people—and that is exactly what the McGovern-Fraser reforms succeeded in doing. Candidates for president were now essentially required to submit themselves to the voters in order to be crowned their party’s nominee. Democratic Party elites, seeing things slipping away, in 1982 convened the Hunt Commission to reform the process yet again. This time they sought to regain some of their influence by mandating that 20 percent of the delegates would not be bound by voter preferences and therefore would be able to choose whomever they wanted to support come convention time. These superdelegates only exist on one side of the party divide however, as the Republicans did not choose to emulate the Democrats this time.

One irony of this back and forth is that America’s presidential nominating process is among the most open and democratic in the world. Most other political parties worldwide do not have any sort of primaries, and many that do limit rank-and-file participation in a variety of ways. Also, some parties screen candidates and, without elite support, one cannot even run for the nomination.

But still, the litany of complaints about our system is long: The primary process goes on forever. It is too expensive for non-elite candidates. Iowa and New Hampshire, two relatively unrepresentative states that lead off the proceedings, have disproportionate influence on the final outcome. The votes of many citizens essentially don’t count because in most instances the contest has been wrapped up before their states’ scheduled primaries and caucuses.

Of course, if your preferred candidate is ultimately victorious, the complaints tend to be muted. But supporters of the losing candidates are often quite vocal in their disparagement of the system—and 2016 was no different in this regard.

If you look at the Democratic race, it was clearly a case of the party deciding for Hillary Clinton before the voting began. Clinton quickly locked in virtually all of the elite endorsements, making her the strongest frontrunner the modern system has ever witnessed. Clinton also benefited from the overwhelming support of those infamous superdelegates. And finally, the Democratic National Committee initially scheduled a relatively small number of debates and broadcasted most of them on Saturday nights, minimizing the potential damage to a Clinton campaign that had huge systematic advantages.

Despite running under a legal and ethical cloud for most of her campaign, and facing a powerful insurgency led by a surprisingly charismatic challenger, Clinton prevailed in the end and became the first woman ever to be nominated by a major political party for president.

On the Republican side, the lead-up to the primaries and caucuses as well as the ultimate outcome could not have been more different. Party elites clearly would not or could not decide on a preferred candidate during the invisible primary period, splitting their support among several broadly acceptable aspirants including Marco Rubio, Jeb Bush, Chris Christie, and John Kasich. This opened the door for Donald Trump to capitalize on a populist anger simmering among the Republican primary electorate. Trump won his party’s nomination without any elite support going into the primaries and caucuses and prevailed despite most party elites preferring anybody but him.

One can already see countervailing pressures on the two major parties resulting from the drama of 2016. Sanders supporters are calling to abolish superdelegates and change states’ primary processes to make them more accessible. And Republican leaders will seek to gain a firmer grip on their nominating process to avoid the debacle that has been Donald Trump’s unlikely candidacy. In fact, we saw this play out earlier this week as anti-Trump forces in Cleveland tried to force various procedural roll call votes as a way of, if not stopping Trump, embarrassing him and his supporters.

No matter the reforms, the struggle between elites and voters will go on.

(Dr. Martin Cohen is an associate professor of political science at James Madison University. He is co-author of the “The Party Decides: Party Nominations Before and After Reform” and author of the forthcoming “Moral Victories,” which will be published by the University of Pennsylvania Press.

Primary Editor: Jessica Suerth. Secondary Editor: Callie Enlow. This piece was posted originally at zocalopublicsquare.org. Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

28

Sat, Feb