CommentsGUEST WORDS--One fact that has received little attention in the current encryption debate is that many categories of individuals rely on strong encryption for their own security.

These include sexual and gender-based rights activists, domestic violence victims, journalists and their sources, and human rights defenders. Strong encryption is necessary to protect fundamental human rights; as one technologist puts it, encryption saves lives.

Encryption, a process of scrambling communications to make them private, is frequently discussed simply as a privacy issue. But the same process that keeps banks’ communications secure is also, for many, a safeguard of many human rights including the right to life. For those who rely on secure communications in sensitive situations, the issue goes far beyond privacy.

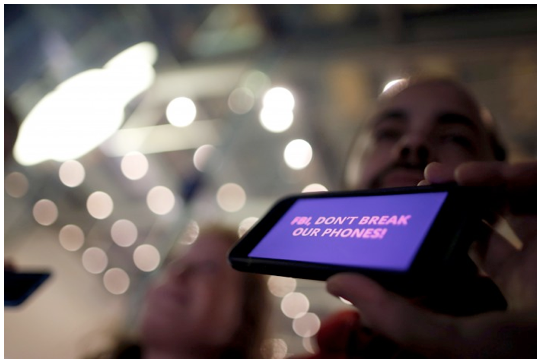

Experts agree that “secure back doors” -- which would give law enforcement secret access to digital storage or communications -- are scientifically impossible. That explains the uproar over a federal magistrate judge’s recent decision ordering Apple to create a backdoor to an iPhone. On Feb. 25, Apple moved to vacate that decision and warned that the FBI is seeking a “dangerous power” in the case.

Back doors are wholly unnecessary for security. Law enforcement agencies already use hacking tools to track electronic communications and circumvent encryption. Information-sharing programs reportedly exist with intelligence agencies, which use keyloggers to record encrypted messages before they are sent. National Security Agency (NSA) supercomputers can even number-crunch to break some encoded messages. And encryption does not shield the “to” and “from” lines of messages -- also known as metadata. The problem is not a lack of tools, but intelligence failures in analyzing existing information -- perhaps one reason former NSA head Michael Hayden rejects the FBI’s position on back doors.

What is not being emphasized enough is how back doors will not only fail to solve this problem, but will also undermine the rights of several categories of people:

Sexual and Gender-Based Rights Activists

In many countries, LGBT individuals rely on encryption tools for their safety. Uganda’s LGBT activists use and teach encryption, for example, because death threats have been directed against some members of the LGBT community in their country and there have been several attempts to pass severely homophobic measures, including one known as the “kill the gays bill.”

Targets of Domestic Violence

In the United States, domestic violence is very often facilitated by technology. Domestic violence victims often are threatened by cyberstalking and phone-tracking malware. The worst cases lead victims to change their names, bank accounts and other identifying information. In response, the National Center on Domestic and Sexual Violence recommends technological solutions for victims.

Psychiatrists and sexual assault counselors may be ethically obliged to encrypt their communications to preserve patient confidentiality. Supporting sexual violence victims means taking strong encryption seriously, because back doors -- particularly on phones -- could be exploited by predators.

Journalists and Their Sources

Free speech and digital rights organizations agree that strong encryption is necessary to protect journalists and their sources. Reporters Without Borders calls it “the only option” to protect dissidents, journalists and their contacts in such countries as China, Vietnam and Tunisia. The Committee to Protect Journalists advises reporters in Syria to use PGP encryption or risk the well-being of sources. Many of the worrisome regimes are extremely well-resourced and are among the first actors to exploit security flaws.

Journalists generally have an ethical obligation to protect the identities of their sources, and the risks are not limited to less democratic countries. In the West, there are numerous cases of journalistic sources facing aggressive persecution or inhumane treatment for talking to the press. The U.S. is widely criticized for its draconian treatment of whistleblowers who disclose information to the media.

Human Rights Defenders and Their Lawyers

Most governments around the world spy on human rights defenders. That spying does not respect attorney-client confidentiality, and, as a result, human rights lawyers are also ripe targets. Bahrain’s government, for instance, is known to hack the communications of lawyers and activists. And in one disturbing case, a human rights lawyer says the government blackmailed him in an effort to stop his work, threatening to distribute a tape -- recorded in secret apparently by government agents -- that showed him and his wife engaged in sex. (The lawyer continued his activism, and eventually he was arrested, tortured and held almost four months before being released on bail.)

The threats faced in many non-Western countries dwarf those posed by NSA surveillance. As fellow human rights lawyer Renata Avila importantly observes, surveillance technologies in the global south “are often more sophisticated, pervasive and abusive than those revealed by Edward Snowden in Western countries.” Governments with access to those technologies have the will and resources to exploit encryption back doors. Should Apple be forced by the U.S. government to construct a back door for one of its products, there would be no stopping other governments from asking the same.

Some U.S. state bar associations, motivated by the increasing risks their clients face worldwide, are advising lawyers to encrypt their communications. That ethical guidance has been offered by bar committees in New York and, earlier this year, in Texas. That caution does little good if it is undermined by technical means.

No Purpose Served by Back Doors

Nearly 200 computer security experts, open-Internet organizations, human rights groups and tech companies recently called on governments worldwide to strengthen encryption.

If U.S. companies can be forced to implement encryption back doors, there will be nothing stopping other countries from demanding the same wherever tech firms do business. And the “bad guys” will simply stop using those tools while other users are left insecure. The type of encryption that offers adequate protection is strong, robust and free from back doors. The threats of globalized terrorism must be addressed with competent solutions, not proposals that undermine the fundamental rights of whole categories of individuals.

(Carey Shenkman works in New York City and is an advocate for strong protections for independent and non-traditional media, focusing primarily on the First Amendment, human rights, and data security. As a lawyer, he represents journalists, publishers, and filmmakers facing political persecution or censorship. This piece posted first at TruthDig. Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.