POLITICAL HERITAGE UNDER FIRE - If ignorance is bliss, the Western world should be ecstatic.

Even as colleges churn out degrees and collect fees, and technology makes information instantly accessible, the basic level of literacy, as measured by such things as reading books and acquainting oneself with the past, is in a precipitous decline. Rather than building a vital world with our technological culture, we are repeating the memes of feudal times, driven by illiteracy, bias and a rejection of the West’s past.

Over half of American adults have a reading level below the equivalent of sixth-grade level (11- to 12-year-olds), and book reading outside of school or work among the young in particular has declined markedly. A survey conducted in 2014 found slightly over half of American children saying they liked to read books ‘for fun’, down from 60 per cent in 2010. This is not just an American trend. A landmark study by University College London tracked 11,000 children born in 2000 up to age 14 and found that only one in 10 ever did any reading in their spare time as teenagers. The Covid-related lockdowns, notes one recent UN study, raised the number of children experiencing reading difficulties from 460million to 584million.

Even before the pandemic, people’s cognitive skills were weakening. Many employers in the US report difficulty finding workers capable of having a serious conversation. Over 60 per cent of applicants are found to be lacking in basic social skills. Today’s teens’ experiences are increasingly limited to what they access on their phones and social media. Rather than opening minds, social media seem to be creating a generation with little ability to communicate in person.

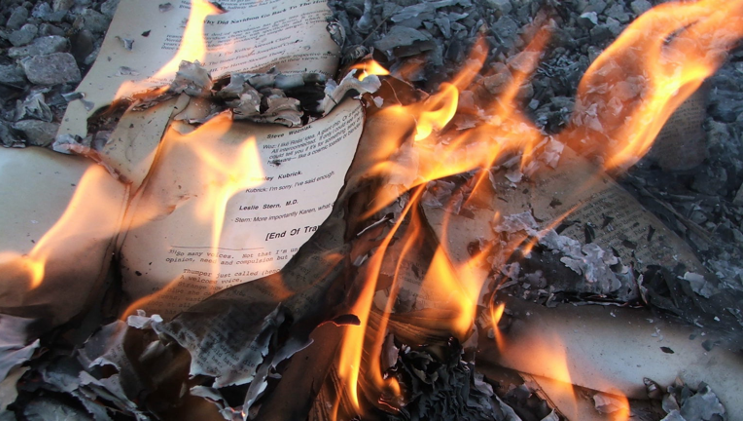

Sites like Facebook and Instagram have been linked to reduced attention spans: research indicates that the average attention span has fallen 50 per cent since 2000, mainly due to social-media use. This loss of literacy comes at a time when much of our education and literary establishment has embraced censorship, while on the right there’s an increasingly Pavlovian embrace of book-banning. Even in defending the common culture, the right forgets the necessity of diverse opinions in a democracy.

Right now, the most influential advocates for banning classical literature from curricula, or removing books non-compliant on issues like gender, are not disgruntled conservatives. No, the assault on studying ‘great books’ and Western culture largely comes from progressive professors with PhDs, and the ever-expanding university bureaucracies and their recent graduates. The embrace of these cultural trends, as former Mother Jones writer Kevin Drum suggests, has emerged as Democrats have moved far more to the left than Republicans have gone further to the right. This is sometimes enforced with mandatory indoctrination sessions and even requirements to sign the woke version of McCarthy-era ‘loyalty oaths’.

In the new schema, the past is seen as racist, ugly and simply too complex for young minds. At many US colleges, books written before 1990 are considered ‘inaccessible’ to students. University policies increasingly marginalise Homer, Confucius, Shakespeare, Milton, Tocqueville or the Founding Fathers. Some books are scorned for having been written by dead white males, who as a group are linked to such horrors as slavery, the subjugation of women and mass poverty. America’s cultural arbiters, such as the National Archives, now consider it necessary to flag up the nation’s founding documents for ‘harmful language’. Ultimately, many of those things that drove Western ascendancy since 1500 – reason, work ethic, family and even science – are being cashiered to create some kind of woke brave new world. And our society seems all the poorer for the loss.

So in today’s academy Chaucer and even Shakespeare can now be avoided by Ivy League English students, while knowledge of Latin or Greek is not required to enter a classics programme. Given the high-level commitment to deconstructing our culture in Western societies, it isn’t surprising that we are seeing lower levels of cultural literacy and a greatly reduced interest in history among the young.

The misanthropic hostility to America’s legacy – which often extends to grade schools – could have grave political consequences. It could lead to the rejection of the most basic principles of a functioning democracy. Young people, for example, are far more likely than their elders to accept limits on freedom of speech. Some 40 per cent of millennials, notes the Pew Research Center, favour suppressing speech deemed offensive to minorities – far more than earlier generations.

Europe is, if anything, moving faster toward marginalising its own heritage. European millennials also display far less faith in democracy and less objection to autocratic government than previous generations, who lived either under dictatorships or in their aftermath. Young Europeans are almost three times as likely as their elders to believe that democracy is failing. Rather than embrace the continent’s storied if often tragic past, noted a recent statement by European scholars, the EU is engaged in an ‘ersatz religious enterprise’ based on post-nationalism, and a rejection of a distinct, historical culture in favour of multiculturalism.

The assault on our political and cultural heritage increasingly defines political conflict. On the left there is an almost nihilistic desire to wipe away the idea that Western cultures leave us anything to embrace. This elite disdain for traditions of country, religion and family has polarised society. It has sparked a predictable right-wing reaction, ranging from Trumpian fulminators to more sophisticated exponents like France’s presidential aspirant terrible, Éric Zemmour.

To date, opposition to the progressive assault on traditional culture has all too often morphed into disdain for minorities who are blamed for undermining national heritage. It’s perhaps a reach to call unpleasant people like Zemmour (an Algerian Jew) ‘a racist’, as the New York Timespredictably did, or the current unpleasant rulers in Hungary or Poland fascists in the Mussolini mode. But they exhibit clear authoritarian tendencies. The fact that some on the right see Putin’s Russia, orthodox and socially conservative, as a role model should give some pause.

But class may be more critical to defining the current cultural conflict. The dominant cultural arbiters in the EU, Canada or US occupy the ‘commanding heights’ of media and politics, but their rejection of traditional culture does not resonate with adults who confront the daily struggle to make a decent living and find usable values for their offspring. This is reflected in the decline of public trust in media, academia, governments and, in the US, even in the now woke military.

Throughout the West, the working and traditional middle class – shopkeepers, small property owners, artisans – are moving towards conservative and even reactionary candidates. In contrast, the old parties of the left in the US, Australia, the UK and across Europe, have embraced the postmodern cultural agenda and lost their old constituencies. Overall, eastern Europe, and its conservative working and middle classes, are now the right’s bulwark against the cultural influence of progressives.

As the retreat from our Western heritage and the collapse of literacy continues, we are reprising the cultural behaviours of the Middle Ages. As late as the mid-15th century, literacy rates in Europe were quite low – five per cent overall in England, though substantially higher in cities and in the more urbanised societies of the Netherlands and Italy. Few women were literate. This changed dramatically after the introduction of the printing press, especially in the cities of northern Europe. By 1650, about half the British population could read. Literacy in the Netherlands soared to about 85 per cent by 1750.

This more literate populace, able to read the Bible, the classics and even scientific studies for themselves, was better equipped to demand rights and oppose injustice and to organise effectively around a common programme. Indeed, a few literate peasants may have had a leading part in the rebellions of the later Middle Ages. High rates of literacy in colonial America allowed traders and mechanics to spread the revolutionary message against the monarchy and helped them organise their resistance, as Benjamin Franklin noted (1).

Although far from perfect in its content, postwar culture was widely shared between cultural arbiters and the middle class. Average Americans in the 1950s were purchasing large numbers of classical works and books by contemporary authors such as Ruth Benedict and Saul Bellow. Many enjoyed watching Shakespeare plays on television, with one production attracting a remarkable 50million viewers (2). There was a rapid growth in the public’s appreciation of museums and classical music, which are both now under unrelenting assault by progressive activists.

Today’s cultural creators sharing and expressing the concerns of the clerisy, have lost touch with much of the mass market. Television audiences for shows like the Academy Awards have been declining. Increasingly prizes rarely go to quality films with broad popularity, such as West Side Story, The Sound of Music, or even The Lord of the Rings film trilogy. Instead, award-winning films, sometimes fine movies in themselves, are largely chosen for their appeal to insiders. At the same time, Hollywood makes most of its money from cartoonish superhero movies, suited to a post-literate audience.

This loss of a common culture and the sense of the past undermines the coherence of society. The idea that someone from another time, conditioned in a separate set of values, might have something to say seems increasingly rare. To be sure British people need to understand the cruelties of empire, but also to celebrate their enormous historic achievements. Cancelling the genius of an island civilisation is a crime against common culture. The enslavement or genocides committed in the settling of North America or Australia should be taught, but so too should the fact that these places provided better lives for settlers and their offspring who number in the hundreds of millions.

We are in danger of returning to a new Dark Ages, when ‘the very mind of man was going through degeneration’, as Henri Pirenne put it, cut off from the traditions and values of our civilisational past (3). If one doesn’t know the foundational principles of our democracy, including individual freedom and open discussion, one is not likely to recognise when they are lost.

Regaining a sense of pride in Western culture and its achievements – while remaining open to newcomers and influences from elsewhere – is essential to recovering the ambition and self-confidence that drove the West’s ascent, from the Age of Exploration to the Space Age. A civilisation can survive only if its members, particularly those with the greatest influence, believe in its basic values.

But if restoring the classical canon is critical, so too is providing a broader vision that accommodates our changing populations. Given the demographic trends not only in Europe but also in North America and Oceania, a xenophobic agenda is likely to be counterproductive, as well as incompatible with a liberal society. Newcomers need to be integrated into the national culture while being free to add their unique characteristics to the host societies.

Such successful societies are by nature expansive, not closed in. Rome became great, Gibbon suggested, in part because it permitted religious heterodoxy and provided outsiders, including former slaves, a chance to rise above their station. In contrast to Athens, where citizenship was restricted, Rome extended citizenship to the farthest boundaries of its empire – by 212, all free people were eligible to be citizens. ‘The grandsons of Gauls, who besieged Julius Caesar at Alesia, commanded legions, governed provinces and were admitted into the Senate of Rome’, wrote Gibbon (4).

Just as diverse peoples found much to emulate in Roman civilisation, the liberal institutions that developed in the West can still appeal to people from radically diverse backgrounds. Chinese, Muslims and Latin Americans migrate mostly to countries that have embraced the liberal values of citizenship, tolerance and the rule of law (5). China under the autocratic Xi Jinping may offer ‘the Chinese dream’, but the number of immigrants from China living in the United States more than doubled between 2000 and 2018, reaching nearly 2.5million. Similar patterns have been seen in both Canada and Australia. There is little such movement to China or most other Asian countries.

Those with the good fortune to live in pluralistic Western-style democracies, rooted in classical culture, should recognise how rare such open societies have been through history, and how much the vitality of these societies is threatened today. Historically, democracy has been like a flame that shines bright for a while – as in Greece and Rome – and then succumbs to autocracy or ossifies into hierarchy.

A future shaped by the best Western values is still possible, if we are willing to embrace it, and teach it to future generations. Such a broad vision will be resisted by the woke, and some nationalists on the right may see inclusivity as too tolerant of change and difference. Books and open discussion are decisive weapons against the rise of post-literate intolerance. This is what helped overwhelm feudalism and could fend off its repeat appearance in our era.

(Joel Kotkin is a spiked columnist, the presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University and executive director of the Urban Reform Institute. His latest book, The Coming of Neo-Feudalism, is out now. Follow him on Twitter: @joelkotkin)