CommentsBEGREEN--The Republican Party's stance on climate change has been shifting. Prominent conservatives who once might have been labeled climate deniers have begun acknowledging the reality that our climate is changing. Though not all have accepted the role of humans in causing that change, many now say that human action must be a part of the solution, releasing conservative climate policies to counter environmental policies from the left, including the Green New Deal.

Whereas Democratic plans focus on government regulation of the oil and gas industries, Republican plans tend to center on technological innovations to combat global warming. Representative Matt Gaetz (R-Florida) called his plan, which focuses on solutions like investment in carbon-capture technology, the "Green Real Deal." Senator Lamar Alexander (R-Tennessee) has called for a "new Manhattan Project" for clean energy, proposing large-scale investment in carbon capture, electric vehicles, and green buildings. Senator John Cornyn (R-Texas) has said he would support legislation to combat climate change with "energy innovation."

Indeed, innovation is a recurring theme so far in Republicans' approaches to climate policy. The conservative lawmakers know their audience: Different types of messaging on climate change are more convincing for conservatives than those that typically appeal to left-leaning voters. Research shows that messaging that focuses on the overwhelming consensus among climate scientists doesn't persuade conservatives to back climate action, but focusing on free-market solutions to climate change does. Unsurprisingly, many Republicans tend to take the view that technological innovations will solve the climate crisis, while stricter regulations will only serve to stymie progress and threaten the economy.

In a recent report, the non-partisan think tank New America found that conservatives are more likely to support solutions to climate change than to admit that it's happening and that humans are to blame. More than 80 percent of Republicans support funding more research into renewable energy, for example, and nearly half support strict carbon dioxide emissions limits for coal-fired power plants.

Even some conservatives who spent their careers on Capitol Hill working to block climate legislation are beginning to incorporate climate change into their messaging. Senator John Barrasso (R-Wyoming), for example, who represents the largest coal-producing state in the nation, has voted against nearly every piece of legislation designed to address climate change since he was elected in 2007. But recently the senator, a long-time supporter of nuclear energy, began mentioning climate change in his calls for more nuclear power—a controversial, but emissions-free energy source. "If we are serious about climate change, we must be serious about expanding our use of nuclear energy," he said at a hearing last month.

In a New York Times op-ed late last year, Barrasso acknowledged that "the climate is changing and we, collectively, have a responsibility to do something about it." But, he wrote, "innovation, not new taxes or punishing global agreements, is the ultimate solution."

The trouble is, without regulation, companies have fewer incentives to innovate. "Trace any innovation back far enough and you find a shaping role for government policy and assistance—not at every stage the dominant driver, but never absent, never 'neutral,'" David Roberts wrote in Vox last month.

Take car exhaust: When U.S. lawmakers designed the Clean Air Act of 1970, they knew our tail pipes were a major source of toxic air pollution that was choking cities across the country. The act gave carmakers five years to reduce emissions of several pollutants by 90 percent. The auto industry warned lawmakers that the regulation would bankrupt carmakers or force them to pass the costs onto consumers, leading to an economic catastrophe either way—an argument that fossil fuel industry and its supporters still use today when lobbying against new regulations. Lawmakers passed the act anyway, and the industry quickly developed and embraced the catalytic converter—a device that strips car exhaust of harmful pollutants and allowed the industry to meet the target just a few years behind schedule.

The Clean Air Act was so successful because, as little as a half-century ago, Americans across the political divide agreed on environmental policy. Both the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 and the Clean Air Act passed the Senate unanimously. In 1990, when the Senate passed an amendment strengthening the act, even Mitch McConnell (R-Kentucky), who tried and failed to weaken the law so it would have less of an effect on the coal industry, voted in favor of it. "I had to choose between cleaner air and the status quo," he said at the time. "I chose cleaner air."

In 2008, John McCain, the late Republican senator from Arizona, ran for president with a campaign that called for swift action to combat global warming. But just eight years later, the Republican presidential candidate who infamously called climate change a Chinese hoax would win the Republican primary, and, eventually, the presidency.

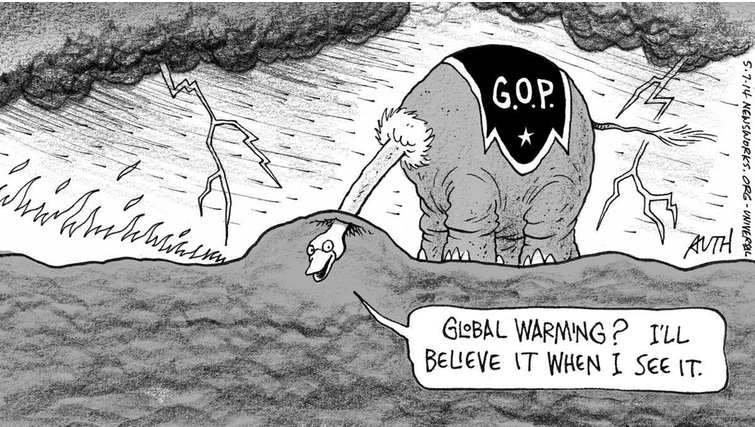

Republicans' and Democrats' views on climate change had been diverging for years by 2016, when President Donald Trump was elected and began systematically rolling back the strict environmental policies, and international agreements, put in place by his Democratic predecessor. While the scientific evidence linking fossil fuel use and increasing carbon dioxide levels to rising temperatures has grown stronger, Republican lawmakers fell prey to a campaign of misinformation from the oil industry to sow doubt about climate science and stymie regulations that might cut into its profits.

So what's changed? The reality of climate change has become harder to ignore outright, even in the U.S. where rising temperatures have fueled increasingly destructive droughts, wildfires, hurricanes, and other extreme weather events in recent years. And along with the climate, public opinion has shifted. The majority of Americans say they believe that climate change is happening—though there is still a steep divide between liberals and conservatives. While 98 percent of liberal Democrats say they think global warming is happening, just 42 percent of conservative Republicans agree according to a report from the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication and George Mason University. However, moderate Republicans and younger conservatives are significantly more likely to care about climate change. A third of Republican Millennials now say that humans activities are behind global warming, according to a survey from the Pew Research Center.

Republican politicians have taken notice of the shift. While environmental groups and critics on the left say that Republicans' climate policies don't go far enough, for the first time in more than a decade, the debate seems to be shifting from one about the existence of climate change to one about how to solve it.

(Kate Wheeling is a staff writer at Pacific Standard, where she specializes in criminal justice and the environment. Posted earlier at PSMag.com)

-cw

Tags: