Comments

PLANNING WATCH - Los Angeles may finally have a new zoning code. The draft document is enormous, weighing in at 1,165 pages and available on-line. The Department of City Planning has been working on this document for years, and the City Planning Commission adopted the current version in August 2022. Since few things move quickly at LA’s City Hall, I want to address two items in this document.

First, the new Zoning Code will only apply to Los Angeles neighborhoods with adopted Community Plans. The remainder of the City will be subject to the existing Zoning Code because most of LA’s 35 Community Plans are more than 20 years old, and it will take years to prepare and adopt new plans. The City Council has only adopted seven Community Plans over the past 16 years, yet according to a 2017 LA City Council directive, Community Plans must be updated every six years. These seven Community Plans are already due for another update. In addition 16 Community Plans are being slowly updated. These updates require several more years to be completed, assuming that staff layoffs, new epidemics, and legal challenges can be dodged.

The remaining 13 Community Plans do not even have an update start date. Based on the slow pace of updating the first batch of 16 Community Plans, it will undoubtedly take many more years until City Planning completes these updates and the City Council adopts them.

If or when the Planning Department updates LA’s 35 Community Plans and the City Council adopts them, the new Zoning Code would apply to the entire city. Until then Los Angeles will be a hodge-podge of old and new zoning codes, a perfect storm for erratic zoning information and enforcement.

Furthermore, regardless of how comprehensive the new code might be, the need for code amendments and zoning variances will continue. As a result, the new Zoning Code will expand as developers respond to swings in interest rates, consumer demand, building designs, and new technology by seeking ad hoc relief from the new Zoning Code’s regulations.

Second, the new zoning code’s Chapter 9 consolidates many existing zoning programs that allow greater parcel density to produce “affordable housing.” As I have previously written, this approach is self-defeating. Zoning Code provisions that allow more density on existing parcels raise their market value. This, in turn, increases the cost of housing. When combined with declining incomes for most people, the number of homeless and overcrowded people increases, despite vacant units.

This is the fatal flaw of relying on market mechanisms to solve the homeless crisis. This does not refute other criticisms, such as the lack of transparency in local homeless programs, but it makes clear why programs to solve homelessness through market housing are a fool’s errand. It also explains why there is such poor record keeping and enforcement of programs to increase the allowed density of existing parcels.

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs): In California each house can already add up to three ADUs, without any regulations controlling their use or rents. The most common ADU is a 1200 square feet house in the backyard. In effect, single family lots become duplexes, even when the ADU becomes a bedroom, studio, or office. Furthermore, a homeowner or investor can legally add a small house on wheels in the backyard, plus a 500 square feet ADU in the main residence.

In addition, Senate Bill 9 allows a developer to buy a single family house, demolish it, subdivide the lot, and build a duplex on each half. Voila, a four-plex appears. Few developers or homeowners are interested in this option, however, since McMansions are already legal, and they are three times the size and cost of a demolished house. Instead, developers only need to sell the McMansion or keep it as an AirBnB short-term rental.

Chapter 9, however, presents many more options for homeowners or developers to pack more rental units into existing parcels, including Affordable Housing Incentive Programs, Community Benefits Programs, General Incentive Programs, and Accessory Dwelling Units. Despite these many options, the number of homeless and overcrowded people continues to rise.

These and similar programs are presented in the draft Los Angeles Zoning Code’s Chapter 9, Public Benefit Systems. Missing, however, is data that these and similar zoning programs have successfully reduced the number of homeless and overcrowded residents in Los Angeles. The beneficiaries are property owners since these programs increase the value of their parcels.

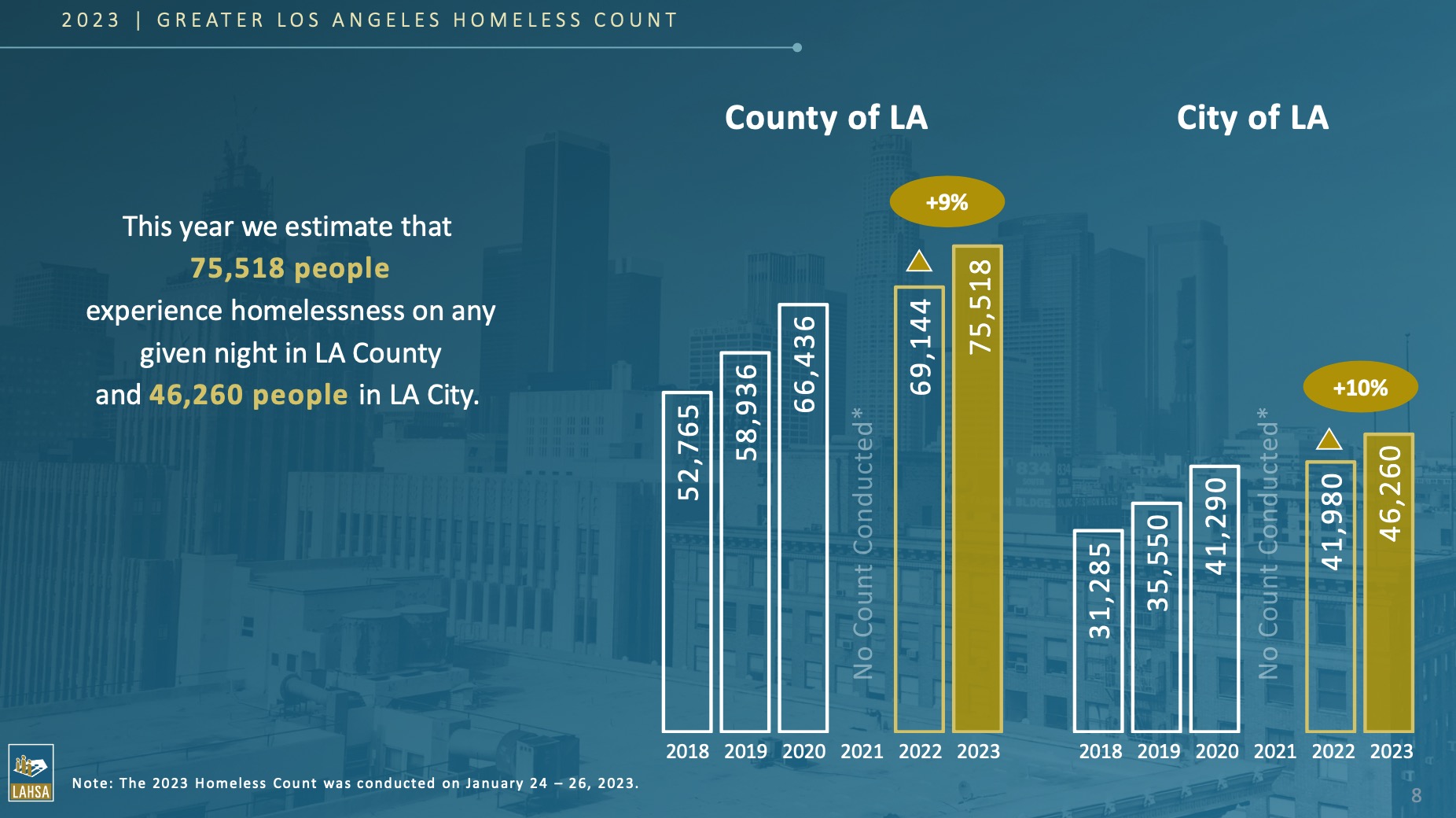

Homeless numbers in Los Angeles County and City between 2018 to 2023

Conclusion: As revealed by the chart above, these zoning programs create homelessness faster than they reduce it. If we could be a fly on the wall in City Hall’s backrooms, I suspect the real estate lobbyists who pushed hard for the new Zoning Code knew that creating affordable units was nothing more than a “feel good” ruse. It is a great cover story for raising property values through deregulation.

(Dick Platkin is a retired LA city planner, who reports on local planning issues for CityWatchLA. He is a board member of United Neighborhoods for Los Angeles (UN4LA). Previous columns are available at the CityWatchLA archives. Please send questions to [email protected].)