Prop M: No Representative Planning, No Vote

TRANSPORTATION POLITICS-Proposition M brings out many conflicting views held in the LA Basin communities and in many suburban areas -- viewpoints of what is needed in the towns, cities and communities regionally. Citizens are demanding better and more representative planning.

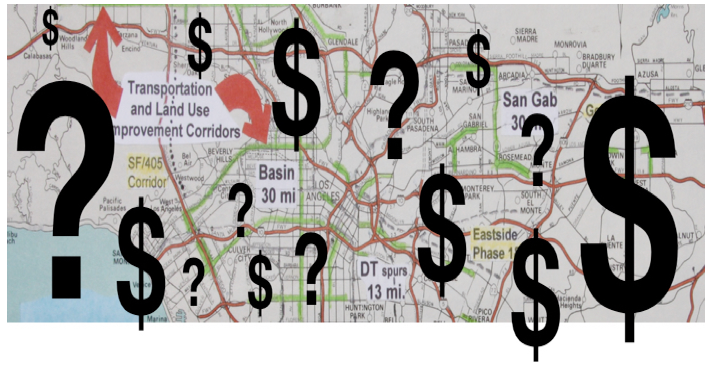

This is important because Prop M is now asking for hundreds of billions in tax dollars that will set a course for spending for decades. Much of the conflict is related to the proposed commuter rail. Due to that extensive and expensive influence, there could be a lifestyle and economic impact for many affected citizens.

This issue is critical because Proposition M does not work physically (can’t put rail in existing boulevards), socially (because of inequity and lack of social mobility options for many), or economically (excessive costs of new corridor impact mitigations). It will lead to over concentration of density (leading to even higher land and housing costs for the majority) and will require a behavior modification for many who would prefer a more convenient and direct means of mobility.

Furthermore, Metro has proposed unworkable and infeasible additions to the transportation system that can’t achieve goals for better mobility or bring about a sufficient reduction in VMT and reduced GHG emissions as required by SB32; it also creates some rail redundancy that puts the whole system in potential jeopardy.

Prop M is being rejected by citizens because of these conflicts and deficiencies. Everyone should take note because there are much better alternatives that do not require such excessive spending and actually are the technological future of transportation in greater Los Angeles.

However, a basic regional commuter rail network and Metrolink are being constructed now, paid for by the existing Measure R and Props A and C. This is what Downtown LA wants and they are on their way to getting it – a DONE DEAL. By purchasing previous rail corridors at low cost, Metro has brought the basic network together along with Metrolink, which is good. The low hanging fruit is being picked.

From here, however, there is a lack of available low cost corridors for urban commuter rail transit. The impacts of forcing such corridors through communities makes it necessary to re-think what is the best way to improve both mobility and the socio-economic circumstances for livability in our communities and region.

Thankfully, there are vehicular innovations emerging for cars and trucks, as well as buses – innovations that can make Bus Rapid Transit truly rapid and with an extensive and very affordable network. These improvements support existing development; and it’s integral, not like old RR lines that were built away from existing suburban towns and city development.

Prop M should be turned down and better planning should be prepared. It may also mean that no such future sales tax increase is needed. Both the presidential candidates and the government in general want to begin increasing Federal spending for infrastructure, so it is very likely the LA County taxpayers do not need to be hit so hard and long as they would be with the Prop M two cent out of every dollar “forever tax.” Federal contributions and better planning can make that possible.

This needed better planning is consistent with not having over-development in the LA Basin communities. It would also turn towards making more urbanizing growth in existing suburbs, bringing sustainability and becoming a way to help achieve climate change goals.

Already there are protests from LA Basin communities about over-development and traffic congestion, a conflict that would increase with new rail-induced development. More rail and associated Transit Oriented Development, especially regional office and commercial land uses, would increase vehicular traffic and the intrusion of cutting through neighborhoods. This is especially so when rail is put into existing boulevards such as Lincoln, Sepulveda, Santa Monica, La Brea, Van Nuys and others, as has been referenced in Prop M. Such a tactic has been identified by the recent Westside Mobility Plan studies as resulting in “unavoidable impacts and increased congestion” plus intrusions into neighborhoods. Neighborhood traffic impacts and social equity impacts would increase. All of that would occur while VMT and GHG emissions are not being reduced.

Fixing LA Basin congestion so there are not excessive GHG emissions as well as reducing the average length of trips in the suburbs with the proximity of urbanizing land use, is a strategy that can massively reduce GHG emissions countywide. It gets the County on the path to the transportation share of reduced emissions to meet SB32 goals. This is meaningful because Prop M will not achieve the necessary reductions in GHG emissions.

As it stands, suburban towns, small cities and communities would not have enough funds to develop transportation improvements that work best for their communities in order to improve the function, livelihood and livability that is needed.

So now we are at the point where community-scaled planning concerns and multi-community connections require a transportation improvement method. Since rail impacts the community scale and brings more congestion, a more integral mode for fixing LA Basin congestion corridors and helping to structure future growth to the suburbs is needed. That kind of innovation is emerging in transportation technologies in both vehicular and innovative roadway use, as we now read about in the media every day.

GHG EMISSION EXAMPLE: If the LA Basin congestion were fixed in the Santa Monica Boulevard corridor and 405 corridor on the Westside, it would be equivalent to the Measure R rail GHG savings of gasoline. The Measure R rail program is taking almost 40 years to be built and more than $20 billion in costs. Fixing the Santa Monica and 405 corridors would achieve the same reductions in gasoline used, would be about one twentieth as much in cost, and would take about 4 years.

By combining advanced vehicular improvements with advanced roadway architecture in selected urban corridors, car, bus and truck modalities are given improved function and become part of the general solution which reduces GHG emissions and VMT growth.

It is evident that the suburbs and dispersed cities of the County want and need to plan for their own growth and sustainability, instead of looking to the LA Basin for job security. In that case, it means evolving existing streets into advanced roadways that support and structure community growth in a timely process, according to their internal needs for growth.

Combined with the envisioned dispersed growth is the objective of reducing VMT by reducing average trip length, due to the proximity of needed land use functions as each community, town and city becomes more self-sufficient.

If you have kept up with transportation strategies of reducing GHG in significant amounts, this will occur by increasing, each year, the CAFE standards of greater mpg for vehicles. This massive reduction in GHG emissions is now in process.

The County TSSP traffic signal program for suburban streets, where signals are spaced greater than two miles apart, is very “cost effective” at reducing GHGs. In the TSSP program, along 220 miles of streets, this is equivalent to reducing 3.74 times the amount that Measure R will reduce -- and at 1/1,000th the cost. Another way of describing the cost efficiency is that $1 of signal synchronization is worth $4,125 put into rail development, as is proposed in Measure R. And more areas of the County can use TSSP.

In the LA Basin, already congested communities can eliminate congestion because “advanced roadways and advanced vehicles” can now come to our streets combined as digital systems.

For this more urban context, where signals are close together, a new innovative roadway architecture can allow continuous flowing traffic, essentially doubling the capacity of normal street lanes that presently have stop-and-go driving. The LA Automatic Traffic Surveillance and Control (ATSAC) system gives the necessary signal timing and brings integration with other related existing areas of the street network. What would be taking place is the “digitization of roadways” in selected portions of the vehicular network, with the new roadway architecture facilitating “continuous flowing traffic” (CFT).

An example of improvement with CFT would be the elimination of the 5 mph traffic congestion on Santa Monica Boulevard in West Hollywood. Today’s failing 5 mph peak period stop-and-go speed has a capacity of around 300 vehicles/lane/hour and is emitting GHGs at about 2.5 times the amount as when traffic flows at 30 mph. A managed speed of 30 mph (not allowing slower or faster traffic,) provides CFT capacity at about 1200 vehicles/lane/hour -- four times as much than the 5 mph failing traffic flow. This solves traffic congestion and GHGe.

In the I-405 corridor and its related cross streets from Sunset to Pico Boulevards, the area encompasses a daily traffic volume of around 680,000 trips per day. It’s a problem that a tunnel for vehicles or a single line of rail transit, however configured, cannot address. The congestion is inherently a vehicular problem where traffic to the Westside is widely dispersed north, south, east and west in the morning and collected again in the PM. So the congestion solution lies with advanced vehicles and roadways with high capacity.

Metro talks about a “rail tunnel” going through the Sepulveda Pass, making a light rail line connection between the Valley and LAX. That would be one expensive line! First, finding a corridor from LAX to WLA, then the tunnel, probably under the 405 from the I-10 to Sherman Oaks or further, would involve enumerable problems. The rationale is flawed in that the through-travel demand is just 42,000 person-trips/day. Given the possible 40% attraction to a rail tunnel being just 17,000 person-trips/day, this would become way too low of a ridership to justify such a construction expenditure.

A much better use of a tunnel through the Sepulveda Pass is for extending the Purple Line Subway to the Valley. That connection has the ability to attract as much as 54,000 person-trips/day ridership (70% of 76,000 travel demand,) in that it not only connects to Westwood and UCLA but goes on to Century City, Beverly Hills and the Wilshire corridor -- all the way to Downtown.

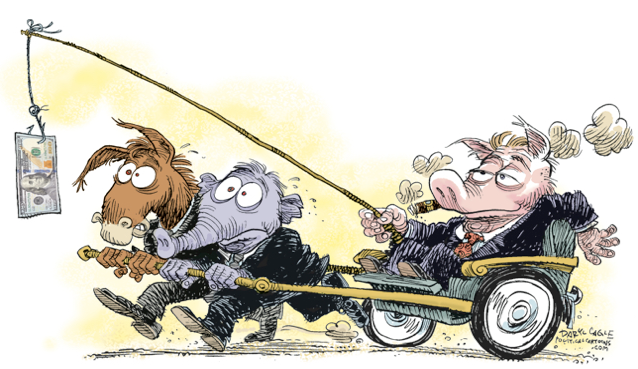

A Boston Consulting Group (bcg.com) report warns about costly low ridership rail lines: “Rail companies may even end up in a downward (economic) spiral with reduced overall ridership. Rail companies’ overall unit costs for all remaining passengers will escalate because of the inherently high proportion of fixed costs in operating a train network. This could trigger price increases or reduced schedules, which would result in a further reduction in ridership.”

Segments that include a costly “rail tunnel” with low ridership, too many low ridership commuter lines and forcing rail into boulevards (where mitigation is costly and there is vehicular competition,) would incur losses threatening to consume the entire rail system with costs -- setting a downward spiral for all of the County system. And the taxpayers would be required to pick up the cost of such losses.

This is why better planning is required in all areas of the County. More citizen participation is needed to define exactly what communities, towns and cities should be. Greater attention must be paid to all the economic costs and benefits.

Citizens, Prop M has the ingredients for creating a rail transit and real estate bubble which would collapse, leaving the County with bankruptcies. VOTE NO ON M!

(Phil Brown AIA, has invented the CFT roadway system improvement by research and development that has occurred over the last twelve years analyzing the Westside traffic problems and the socio-economic needs of Greater Los Angeles. Contact is available through the website FlowBlvd.com as well as postings of his previous recent CityWatch articles.) Edited for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

Let’s start at the beginning. In 1934, Clinton Lathrop, Sr. and Jean Lathrop purchased the land on which the property at 5303 ½ Hermitage sits. (Photo left.) This property now contains four residential units.

Let’s start at the beginning. In 1934, Clinton Lathrop, Sr. and Jean Lathrop purchased the land on which the property at 5303 ½ Hermitage sits. (Photo left.) This property now contains four residential units.

And they were. On January 10, 2014, the men who murdered Matthew

And they were. On January 10, 2014, the men who murdered Matthew  Everyone knows how wrong I think Los Angeles City Charter Amendment Measure RRR:

Everyone knows how wrong I think Los Angeles City Charter Amendment Measure RRR:

Ellis, at age 43, is also a leader in state Democratic circles. She is recording secretary of the state party's African American Caucus and a member of the party's Finance Committee.

Ellis, at age 43, is also a leader in state Democratic circles. She is recording secretary of the state party's African American Caucus and a member of the party's Finance Committee.

To attack the problem, BBLA presents two goals. The first is to provide a series of carrot-and-stick incentives to developers along transit corridors to include a large number of affordable housing units in their new developments. This would essentially refuse to allow the general plan amendments and zoning changes that are needed for almost any new large development, along transit routes, unless developers either build a percentage of units to be affordable, or pay into the city’s affordable housing trust fund so as to allow units to be built elsewhere.

To attack the problem, BBLA presents two goals. The first is to provide a series of carrot-and-stick incentives to developers along transit corridors to include a large number of affordable housing units in their new developments. This would essentially refuse to allow the general plan amendments and zoning changes that are needed for almost any new large development, along transit routes, unless developers either build a percentage of units to be affordable, or pay into the city’s affordable housing trust fund so as to allow units to be built elsewhere.

Well, maybe so. But Weinstein experienced the same fury and frustration that thousands of powerless Angelenos feel when they wake up one morning to see a tower under construction next door on land that wasn’t supposed to allow such structures. If they investigate, they likely discover that – surprise! – a deal was cut in City Hall.

Well, maybe so. But Weinstein experienced the same fury and frustration that thousands of powerless Angelenos feel when they wake up one morning to see a tower under construction next door on land that wasn’t supposed to allow such structures. If they investigate, they likely discover that – surprise! – a deal was cut in City Hall.