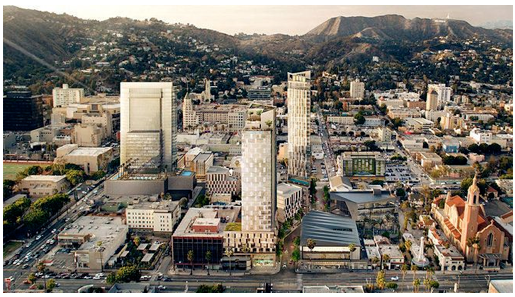

DWP Union on Brink of Hefty New Labor Agreement … Not a Peep from NCs or Ratepayer Advocate

GELFAND’S WORLD--Saturday was full of irony. The Los Angeles Times published an editorial that raised red flags about the way the city's elected officials are trying to sneak through a large pay raise for employees of the LA Department of Water and Power (LADWP). The Times had previously published a story by David Zahniser and Dakota Smith revealing the sordid details.