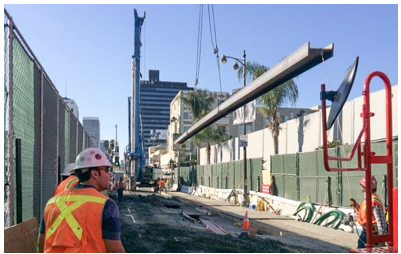

CommentsPLATKIN ON PLANNING-If a public agency is going to spend $8 billion dollars on many miles of new subway, it makes sense to prepare station area plans that boost ridership. Yet, in Los Angeles the Purple Line Extension, pictured above, is falling through the cracks. Both METRO and the City of Los Angeles continue to make choices that will eventually reduce ridership at the new subway stations. Why? As far as I can determine, their goal is to maximize real estate development at and near subway stations, not to maximize ridership.

To understand what is really going on, lets take a deep a dive into the planning history of subway construction Los Angeles. At CityWatch I recently described excellent – but ultimately rejected -- planning studies and zoning ordinances for the original 13 MetroRail stations. In the 1980s the Southern California Rapid Transit District (SCRTD), now called METRO, commissioned the Los Angeles Department of City Planning to prepare these 13-station area specific plans. Long moth-balled at the City of LA’s Piper Tech archives, these plans could easily be pulled out of a file cabinet and become the model for new Purple Line station area plans. Los Angeles would than have station area plans that prioritized ridership, not real estate development.

Political Barriers to Transit Oriented Communities: But now, over 30 years later, this simple process won’t be easy for several political reasons. In addition to METRO’s and City Hall’s developer-driven fixation to use mass transit as a pretext for zoning deregulation, there is little public pressure for passenger amenities at the three Purple Line stations. Called Transit Oriented Districts or Transit Oriented Communities (TOCs), this passenger-oriented approach is straightforward. In METRO’s own words, “TOCs represent an approach to development focused on compact, walkable and bikeable places in a community context (rather than focusing on a single development parcel), integrated with transit.”

I would also add that METRO’s term “development” (i.e., private real estate investment) should be replaced with “affordable housing.” This is because these residences would house those future transit-adjacent residents most likely to become bus and subway passengers.

But this great theory has no connection to METRO’s practice on the Purple Line Extension. Furthermore, there are two very different groups in Los Angeles that are at odds with this crucial approach to transit planning. In their own way they create extra barriers to true passenger-oriented planning on Wilshire Boulevard and adjacent neighborhoods.

On one hand, the cynics ignore real Transit Oriented Districts/Communities. They look at Los Angeles and see a metropolitan area where driving is the favored transportation mode, where bicycling is scary, and where busses and subways are a hassle to use. To their credit, the cynics know that most mass transit use in Los Angeles is involuntary. Most of those on busses and subways are the poor, the disabled, the young, and the elderly. The cynics conclude, therefore, that it is nearly impossible to get other Angelenos out of their cars and onto busses or subways. Their cynicism is easy to understand, but there are planning options that that would help many of them overcome their cynicism about strategically increasing transit ridership.

On the other hand, Transit Oriented Communities are blocked by the market fundamentalists, who some people now call WIMBYs (Wall Street in My Backyard). These groups have a one-size-fits-all program to increase transit ridership without spending a public or private dime on neighborhood amenities. Their simple solution is to jettison any zoning and environmental laws that impede real estate investors from building market housing to their pocketbook’s content. I used to think that these “build-more-housing” crusaders were recently graduated Young Republican types on the lookout for business ventures, but several readers recently brought me up to speed about them.

They linked me to well researched articles documenting how YIMBY’s and similar free-market housing backers are directly tied to major private sector investors, such as the Central City Association, to real estate developers, and to other commercial interests, especially high-tech investors and Silicon Valley.

Not surprisingly, these local market fundamentalists gladly became a public voice for the major real estate companies who funded the no on S campaign in Los Angeles. On the stump, they faithfully parroted SG&A Campaign’s deceptive no on S talking points. They repeatedly smeared a voter initiative whose adoption would have quickly updated the Los Angeles General Plan and mandated a more careful review of discretionary zoning waivers as a spurious “housing ban.”

A year later their approach to the Purple Line is cut from the same no on S cloth. They want to up-plan station areas above forecast population levels, rezone local parcels for bigger buildings, up-zone nearby single-family home neighborhoods for apartments, and eliminate any parking requirements. What they do not call for is new station area housing to be affordable or for transit-oriented public improvements, such as bicycle and automobile parking, pedestrian enhancements, and bus and car interfaces at the new subway stations.

Building Transit with Passengers in Mind: Sandwiched in between the cynics and the WIMBY’s, however, are advocates like mewho call for transit to be thoughtfully planned. Station areas should be designed to transparently guide Angelenos out of their cars and onto busses and subways. According to David Owen, in his masterful Green Metropolis, the trick is to make mass transit convenient. He argues that it is a waste of time to harangue people about the benefits of mass transit. Instead, cities and transit agencies must comprehensively upgrade their built environment to make busses, light rail, and heavy rail simple, safe, affordable, and comfortable to use. In a word, he calls for enhanced Transit Oriented Districts/Communities. In Los Angeles that means translating METRO’s wonderful words into actual public improvements at the Wilshire/LaBrea, Wilshire/Fairfax, and Wilshire/LaCienega Purple Line subway stations.

Unfortunately, David Owen’s approach has few takers at either METRO or LA’s City Hall. The new subway will be hard to access because neither METRO nor LADOT is building any interface or facilities for pedestrians, cars (Park 'n Ride, Kiss 'n Ride), busses, taxis and ubers, and bicycles at the three Purple Line stations. Meanwhile Wilshire Boulevard already has zoning that allows unlimited height, which means high-density by-right commercial and residential buildings, not affordable housing. The future transit-adjacent tenants will own cars and continue to drive them most of the time.

Unless subject to major revisions in the next few years, when the Purple Line opens for passengers in 2023 I fail to see how the market-based approach of METRO, LA’s City Hall, and the WIMBYs will work. As for the cynics, the jury is still out. Based on the template of the land use ordinance for the Exposition Line, increasing by-right building densities will remain the core principle. Off-site improvements, especially affordable housing, improved sidewalks, and bicycle infrastructure will remain unfunded. Ditto for such on-site improvements as kiosks, bathrooms, and Kiss ‘n Ride and Park ‘n Ride.

Doing Transit Right: This is why I argue that the barely hidden agenda of rail projects in Los Angeles is to revive real estate in older parts of the city, not to move people. In fact, urban sociologist, Alan Whitt, did a classic study of BART and MetroRail, “Elites and Mass Transportation: The Dialectics of Power,” to prove this hypothesis. His research has withstood the test of time, and it indicates that when completed, the Purple Line extension will also become a predictable disappointment. It will usher in more market housing on Wilshire Boulevard, but much of this new housing will go begging for tenants. In fact, this is already the case in the Miracle Mile, even with its exemplary express METRO bus service. When you drive by the Miracle Mile’s many new apartment buildings at night, most units are still dark.

Despite METRO, City Hall, and both the cynics and free-marketeers, there are nevertheless many ways that Los Angeles could and should become a transit-oriented city. But this will take more than the camp followers of real estate speculators clamoring for more transit-adjacent market housing near bus and subway stops.

To truly get people out of their cars, we absolutely need Transit Oriented Districts/Communities. This requires dedicated public funds for facilities at and near station sites to serve people in busses, uber, cars, vans, and on foot. It also should include special station vehicle entrance lanes and a full range of pedestrian access improvements, such as streetlights, wider sidewalks, and ADA curb cuts. It also means reliable bus and rail schedules, shorter headways, safe and comfortable buses and subway cars, and heavily subsidized fares. Next, it should include expanded public services and infrastructure to accommodate more people living in and traveling through neighborhoods near mass transit.

As for the housing component, if we want the new tenants to become transit users, then the new station area apartments should be highly affordable and the new tenants should be transit dependent, drawn from the pool of 600,000 eligible people on the Section 8 housing list in Los Angeles.

The time is short to avoid another expensive boondoggle.

(Dick Platkin is a former Los Angele city planner who reports on planning controversies in Los Angeles. Please send any comments or corrections to [email protected].) Prepped for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

13

Fri, Mar