Rx for Chaos: Healthcare Is Too Important for Political Horsepuckey

EASTSIDER-Having negotiated and mediated a good number of healthcare agreements all over the State of California for a lot of years, I have a reasonable understanding of the fundamentals of how these systems work. And after being inundated with all the highly politicized nonsense from both political parties lately, I say, enough!

As long as we have a healthcare system which is underwritten by insurance companies, the mathematics of healthcare is simple. Hat tip to Dave Winer, a NYC (Queens) software developer and author of the Scripting News blog, who hit the real issue right on: ”The insurance industry, left to a completely free market, will only insure young, healthy people, and will cancel their policies as soon as they get sick.”

In the current “debate” in Washington D.C., I don’t think it matters too much whether the politicians are Democrats or Republicans. They all take in gobs of personal money from the health insurance industry and big pharma so that they can stay in office -- even as they tell you and me how much they care while they count their take.

Be it Chuck Schumer and Hillary Clinton, or President Trump and Representative Tom Price (now Secretary of Health and Human Services,) they all take money from the trough. I will, however, admit that Tom Price personally investing in a joint replacement company and then introducing legislation to benefit them, was over the top, even for D.C. On the other hand, what he did is legal for legislators (who make their own rules,) and Zimmer Bionet Tom, as we can now call him, didn’t do anything that a whole bunch of other legislators in both houses of Congress haven’t done in the past.

The reality of medical care is that none of us really know when or how much of it we will need. So there has to be some kind of a cushion against life-threatening medical events, or long term illnesses that require expensive treatments, such as dialysis, organ transplants, etc. Otherwise, to put it bluntly, we can get sicker and even die.

Insurance companies have no economic interest in covering any of this stuff. At the same time, rich people have lobbied Congress so that they don’t have to pay for dialysis, organ transplants, or special needs care. The fact that you and I also benefited from these changes was incidental. Congress, of course goes with the bucks and passes such legislation. It is not a coincidence that it was Ronald Reagan who passed the ADA; his donor base wanted it.

The Math

The healthcare equation is that insurance companies don’t want to lose any money on their insurance, and you and I don’t want to get an expensive medical condition, and then get real sick or die because we can’t pay for the medical care. This affects all of us, every person in the United States. Absent some resolution to this conflict, we are all one major medical event away from bankruptcy, or worse.

Think about it. One major event -- be it long term unemployment, divorce, or major medical emergency -- away from bankruptcy. I’m not making this up. Look at The Two Income Trap, by Elizabeth Warren and her daughter, Amelia Warren Tyagi, written way back in 2003. It’s an impressive (and depressing) read about bankruptcy, a long time before the financial crisis that beggared all of us (except for the banks that caused it.)

There is really only one entity that has the resources to cover that inherent conflict -- and, you got it, it’s the Government. Because we are really talking about how much risk the insurance industry is prepared to cover (not much) at what cost (a lot), and who’s going to pay for the rest your and my unmet healthcare costs. Realistically, the only entities that can do this are government agencies. And since they govern (and tax) all 360 million of us in the United States, the Feds have the deepest pockets.

How much the Feds could cover vs. how much state and local entities could cover is pretty much a redistribution of costs issue, since the tax base is progressively smaller as you go down the food chain. Yet the statistical risks for all of us are roughly the same no matter where we happen to reside. A very small state, county or city is simply not going to be able to provide the cushion that the Federal government can.

That’s the math.

All the stuff you and I see on TV, hear about on the radio, or that is pushed out to us via social media and our mailboxes, is mostly just noise. Most of it is smoke and mirrors, designed to get you and me to vote for brand X or brand Y, like that will really fix our fundamental healthcare problems.

Truth is Bernie Sanders was right in his analysis of healthcare, and he paid for it by having both the establishment DNC and RNC try to bury him. Whether or not the government can afford to go to his model, or should, is a public policy discussion that needs to occur and never really has. Instead we get this silliness.

Budget Cycles and the Cliff

The timing of all of the proposed changes to our healthcare system is not propitious, either. Most public agencies and corporations operate on one of two budget cycles: July 1 - June 30, or January 1 - December 31. Add in to this the fact that open enrollment for most healthcare providers is October/November for January 1 implementation. In order for them to do the necessary premium calculations, the data and coverage changes need to be in place well before summer.

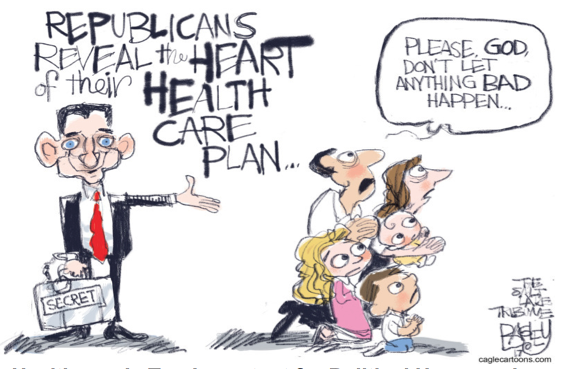

So here we are in March with the President and the Republicans playing around with what they call the “repeal and replacement” of Obamacare. After braying the same mantra for about seven years, it is clear that they didn’t have a clue what that slogan really meant. And for their part, the Dems have refused to play and are saying, “You break it, you own it.” Wonderful.

If you are an insurer, if you are a small business person, if you are a public agency with a July 1 budget deadline, or if you are just a consumer at the mercy of all of these parties, this is incredibly anxiety producing.

All that “striking while the iron is hot” rhetoric over healthcare is going to do is to make every insurer nuts as they try to figure out what premiums they will have to charge for next year. And they will have to take into account the impact for the rest of this year as hospitals, doctors, clinics and insurers have to make mid-year adjustments.

The Insurers

It’s a prescription for chaos, even if all the insurers were playing fair. And let us not be deceived -- they are not all playing fair. I keep referring to Aetna as being a poster child for cheating, so let’s take a look at the details. First, they are one of the two largest insurance companies in the “health services industry” space. Whatever they do is therefore a big deal.

Second, their mega-merger with Humana, another large player in the Medicaid and Medicare space, was a fix. They got caught by a federal judge lying about their decision to drop out of some 17 state exchanges on the grounds that they were losing money. Turns out that they threatened the Feds to do this if the Feds tried to block their merger with Humana. You can read about the skullduggery here.

While Aetna called off the merger after being nailed by a federal judge, the moves to lessen, rather than encourage, competition in the Obamacare world have been marching on. The other 800 pound gorilla in the Obamacare game is Anthem Blue Cross, and they too are engaging in mergers to limit choice. You can read all about the insurance carriers shrinking our choices for Obamacare here, notwithstanding the blah blah blah of most news media.

Whatever people’s ideology or political identification, let’s agree on one thing: insurance companies are in the business of making a profit, period. They are going to budget and set rates based on very conservative assumptions that will keep their CEOs employed.

Most of the media reports over the Republican healthcare bill concern saving money, and how ok it is to charge folks from 60-65 more money because they “use” medical care more than younger people. Egad! You think?

Here’s a modest proposal that will save a lot of money. Stop paying for organ transplants, stop paying for dialysis, and stop paying for long term care for the elderly. It would be really cost effective and save a ton of money! Insurance companies would love it. Heck, repeal the Special Ed statute. And make Congress have the same healthcare that you and I have.

Anyone think they will do it?

The Takeaway

Here’s the practical problem: while the Republicans have elected to embrace Speaker Ryan’s plan without any substantive conversations with the Democrats, their math simply doesn’t work. A bill which pushes some 14 million poor and older Americans out of medical insurance while the relatively affluent get significant tax breaks is something that I cannot believe our political system will countenance.

At the same time, the Establishment, limousine liberal Democratic leadership of Chuck Schumer in the Senate and Nancy Pelosi in the House seems incapable of doing much more than ignoring the fact that they lost the election and are still trying to punish the Republicans for their choice of a deeply flawed candidate -- even as they themselves repudiated Bernie Sanders in every way possible.

Well, we are all Americans. We all deserve affordable healthcare no matter who we are. What is missing here and deeply troubling, is that if the Republican effort fails, there is no Plan B being worked on by the few adults left in our political system, be they Republican or Democrat – at least that I’m aware of. This is not good and somebody needs to get crackin’ now.

Remember, the ACA (Obamacare) is not sustainable in its current form after all that has happened in the last year, and while the big health insurance carriers are good at evading antitrust and gaming the system, I haven’t seen them or big pharma come up with anything sustainable either.

We need to start electing politicians at every level who are reasonably honest and interested in actually representing you and me instead of the deep pocketed political parties and their owners. As long as election turnouts are in the under 20% range (heck, in LA that would be a big increase,) we’re going to keep getting what we got.

Get involved, pay attention…and vote!

(Tony Butka is an Eastside community activist, who has served on a neighborhood council, has a background in government and is a contributor to CityWatch.) Edited for CityWatch by Linda Abrams.

Attempting to become Jackson-like, Donald Trump styles himself as the leader of a “populist” movement he energized with his “America First!” and “Make America Great Again!” slogans as he played on nativist sentiments. Such leanings are an identifying hallmark of Andrew Jackson, who shifted political power from the established elites to the ordinary voters, and played a leading role in granting all white males the right to vote, not just white male property owners. This was part of Jackson’s program of “Jacksonian Democracy” that morphed into the creation of the Democratic Party that, in turn, replaced Thomas Jefferson’s agrarian-based Democratic-Republican Party, changing American political history forever.

Attempting to become Jackson-like, Donald Trump styles himself as the leader of a “populist” movement he energized with his “America First!” and “Make America Great Again!” slogans as he played on nativist sentiments. Such leanings are an identifying hallmark of Andrew Jackson, who shifted political power from the established elites to the ordinary voters, and played a leading role in granting all white males the right to vote, not just white male property owners. This was part of Jackson’s program of “Jacksonian Democracy” that morphed into the creation of the Democratic Party that, in turn, replaced Thomas Jefferson’s agrarian-based Democratic-Republican Party, changing American political history forever.