CIVIL RIGHTS-In California, a driver who commits offenses as minor as driving without a seatbelt or littering faces a $490 fine, according to a new report by a coalition of civil rights groups, entitled “Not Just a Ferguson Problem: How Traffic Courts Drive Inequality in California.”

Worse, if the driver, who may not be able to afford to pay such a fine, does not pay it off quickly enough or fails to appear in court, the consequence is a suspended license – a consequence that prevents them from driving to work to earn the money they need to pay off their fine.

The result is a Catch-22, where the only way to raise the money to gain back their license to drive is to drive without a license and risk even more fines for doing so.

This predicament mirrors law enforcement practices in Ferguson that were exposed by the Department of Justice in March.

Before the DOJ revealed patterns of egregious racial profiling and discrimination in the city, a group of civil rights attorneys filed a lawsuit claiming municipal courts in Ferguson were arresting and jailing an alarming number of people for unpaid traffic violations and other minor offenses. In 2013 alone, 33,000 arrest warrants were issued for Ferguson residents and people living in nearby counties, as courts raked in $2.6 million.

But before the lawsuit was filed, most people weren’t aware of the egregious amounts of debt incurred from court fees each year.

Sadly, Ferguson isn’t the only place in America with a court system that thrives off of poor people’s debts. In California, four million people possess suspended licenses for failing to pay traffic citations — many of which have nothing to do with driving — and are subsequently thrust into a hole of debt they cannot climb out of.

“In today’s society, driving is often a lifeline to work, health care, and education. When cities discriminatorily enforce traffic laws, when we suspend licenses for people who cannot pay a citation, when we close the courthouse doors to people who are poor, we are limiting families’ growth and survival,” the authors stated.

When California state residents are issued a traffic citation, for offenses ranging from driving without a seat belt to vandalism, misplaced registration stickers, broken taillights, truancy, not officially changing a home address, littering, or sleeping on a sidewalk, they receive a $490 ticket. In response to the 2008 recession, the state raised the fine amount from its baseline of $100 by attaching additional statutory fees.

When people don’t pay off tickets or appear in court to discuss the citations by an assigned deadline, they’re fined a $300 civil assessment fee and have their driver’s licenses suspended. Those who cannot pay $490 are therefore burdened by more debt.

To make matters worse, missing a deadline automatically bars people from appearing in court, until the entire sum is paid. Therefore, people whose licenses have been suspended cannot plead their innocence, learn about potential payment plans (including community service alternatives), or explain the reasons for why they didn’t pay on time. In many cases, people fail to show up in court simply because they never received an official notice in the mail.

Often, original tickets handed over by offices are illegible, so the information is unclear from the get-go. And individuals who are able to go to court and demonstrate their inability to pay off a ticket right away aren’t exempt from costly fees. In many cases, they still have to pay to set up a payment plan, which require arbitrary minimums established by privately contracted collection agencies.

The consequences of such court policies extend beyond burgeoning debt, as suspended licenses create numerous hurdles for people trying to pay off their tickets.

On one hand, people in this predicament cannot legally drive to and from work and have to resort to unreliable public transit to get to their place of employment. Those who have no choice but to drive with a suspended license face $300-$1,000 fines and six months behind bars, for a first-time offense.

On the other hand, a significant percent of jobs that low and middle class typically occupy, such as construction, delivery service, and home health care, require licenses. It’s also commonplace for employers to require licenses for jobs that require no driving at all. In contrast, drivers cited for DUIs can seek permission to drive to work on a restricted license.

Additionally, Californians with unpaid fines build up a bad credit report, so renting or purchasing homes becomes much more difficult. Arrest warrants, which are regularly issued to people who fail to pay non-traffic municipal violations, such as littering, make finding a job or house that much more challenging.

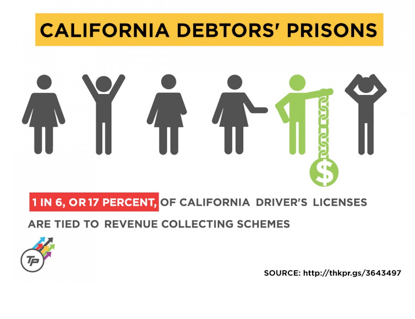

In the last eight years, the DMV has moved to suspend 4.2 million licenses. Between 2011-2012, 60 percent of the funds were funneled to the state, two-thirds of which were distributed to court construction and operations. But because people cannot afford to pay their fines, court-ordered debt has reached $10 billion. Today, one in six, or 17 percent of California licenses are tied to a revenue collecting scheme that exacerbates economic insecurity to benefit county courts.

According to a report published by the U.S. Census in 2014, 8.9 million Californians live in poverty. People in this category are generally the ones who cannot afford to pay off citations. And as in Ferguson, the majority of people issued traffic violations are black or Latino.

The traffic court study concluded that 70.4 percent of people who asked for legal assistance pertaining to driver’s licenses at a San Francisco clinic were black. African Americans only account for six percent of the city’s population. Sacramento and San Diego driver stops followed a similar pattern. Although they only make up 5.5 percent of San Diego’s population, African Americans were involved in 11.2 percent and 23.4 percent of traffic stops and searches, respectively. Making up 7.2 and 8.6 percent of two Sacramento neighborhoods, black people accounted for 22.4 and 27.7 percent of driving stops.

San Francisco resident Thaddeus Ford became homeless after he couldn’t pay off several minor offenses.

Sometime in 2008, Ford was pulled over while he was in the process of moving a friend’s unregistered car without plates from one parking spot to another. It was then that he discovered he was driving with a suspended license for failing to pay $1,400 on a car that he previously sold. Even though he didn’t receive the tickets himself, the fact that his name was on the vehicle meant he was responsible for paying.

But after he was informed of the suspended license, Ford, a cab driver, lost his job. Without the right documentation, no employers would hire him, and he eventually wound up without a home.

Today, Ford is living in a transitional house, and was able to secure an in-home care position after promising his employer that he would obtain a license within three months. Luckily, he was able to enlist the help of the attorneys from the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights, a civil legal aid organization, who were able to secure a payment plan for Ford and convince the courts to issue a license, which he received minutes before talking to ThinkProgress.

“If they want these fines paid, they have to give everybody a chance to get a job,” he said.

Carlos Smith, a 45-year-old Oakland resident, shared similar feelings. “It makes you feel like less of a man,” he told ThinkProgress.

Smith was forced to leave his general contracting job after a 2008 carjacking left him disabled. Turned down by Social Security on multiple occasions, Smith has lived on general assistance for close to six years.

When he went to the DMV for a temporary license in 2013, he learned that he had an outstanding ticket from 2008, and was denied the license. In addition to the initial $500 fine, $600 was added for failing to appear in court, bringing the total owed to $1,100.

Since then, he’s been cited for a red light violation and failing to provide proof of insurance — two $500 fines — and additional fees for failing to pay off the tickets before the assigned deadlines. He also has to drive to and from medical appointments illegally.

After watching his wife work day-in and day-out to support his family, Smith decided to go back to school for construction management and building codes. With two additional degrees, he hopes he can get back to work in the near future.

“It’s very stressful. Only religion and my faith in God keeps me going,” he said.

(Carimah Townes is the Criminal Justice Reporter for ThinkProgress … where this piece was first posted. She received a B.A. in political science from UCLA, where she also minored in cultural anthropology.) Graphics credit: Dylan Petrohilos

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 13 Issue 30

Pub: Apr 10, 2015

Sidebar

Our mission is to promote and facilitate civic engagement and neighborhood empowerment, and to hold area government and its politicians accountable.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

CityWatch Los Angeles

Politics. Perspective. Participation.

08

Sun, Feb