GUEST WORDS-Election Day is over and at the time of this writing, before 8:00 p.m. on Tuesday, November 4 neither of us knows who will ultimately be the Assembly member for the 64th District in Los Angeles County.

While the two of us have some constituencies in common others are distinctly dissimilar. Although we often agree on policy and politics, other times we do not. Each of us bears a different charge --- to legislate on one end of the spectrum and to advocate on the other end. Yet, we share ”a common goal and a common problem” which is why we’re writing this without knowing who will represent the more than 400,000 constituents of Assembly District 64.

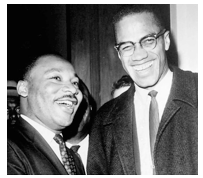

In 1964, Black nationalist (or militant depending on your worldview) Malcolm X wrote The Ballot or the Bullet, a manifesto via discourse on the economic, social and political condition of African Americans. He cautioned us to wade carefully into the electoral process and to cast our ballots deliberately or not at all.

At a time when there were few African American elected officials, particularly those representing non-African American constituencies, X challenged us to model self-reliance and self-respect, and to do it in a manner that would change both the image and circumstances of African Americans. He challenged us to consider our shared problems, our shared goals and how we comported, conducted and portrayed ourselves as well as how we allowed ourselves to be perceived, depicted and treated. Achieving this type of self-reliance would be crucial to the narrative that surrounded us.

In order to truly define our communities and our circumstance, he felt we needed “to wake up and start looking at it like it is, and trying to understand it like it is; and then we can deal with it like it is.” He challenged our notion of fear and “of oppression, exploitation and degradation.”

In 1964, fear was the great motivator that could be turned on its head by the utilization of the ballot or the bullet. Today, political consultants advise that fear is still the great motivator for voters, more than any other self-interest. In a tight campaign, particularly between rivals from the same party or background, conventional wisdom says that the only way to differentiate between the two is to “go negative”, often best achieved by churning up fear among voters.

The question then becomes what are the images of fear? The 1988 ad titled “Weekend Passes”, created by the so-called National Security Political Action Committee featuring convicted felon Willie Horton became the benchmark of negative political ads: An African American man out on release as part of a weekend furlough program supported by then Massachusetts Governor Michael Dukakis raped a woman and assaulted her fiancé.

The image and the message were as clear then as they were this year in Nebraska when the National Republican Campaign Committee ran an ad against State Senator Brad Ashford, titled “Nikko,” featuring a face-tattooed African American convicted felon who had been released vis-à-vis the state’s “good-time” law for which Ashford had voted.

It is beyond disturbing that in the years between “Weekend Passes” and “Nikko” the image of an African American man is still used to invoke fear. Particularly in the wake of the killings off countless young African Americans from Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin to Jordan Davis and Eric Garner.

As elected officials and activists we protest and decry these senseless murders of African American youth at the hands of police officers and fellow Americans who “feared” for their lives; and, we challenge the media to fairly and accurately report the circumstances surrounding the murders while not furthering the stereotypes of African Americans.

{module [862]}

{module [662]}

As those who engage in campaigns our charge becomes more difficult when, in the pursuit of an electoral “win” as in the case of the campaign for Assembly District 64 in which two African American men found themselves pitted against each other, the decision was made to use imagery that furthered stereotypes. How do we protest the images in mainstream media of the African American man invoking fear if we sanction it in our own campaigns? In order to achieve full electoral equality, we cannot be above critiquing each other and stating the facts as we know them. The question is, prospectively, when is it too much?

In the same year Malcolm X gave the Ballot and the Bullet speech, the Supreme Court ruled on the obscenity case of Jacobellis v. Ohio in which Justice Potter Stewart wrote that “hard-core pornography” was hard to define, but “I know it when I see it.”

In the same year Malcolm X gave the Ballot and the Bullet speech, the Supreme Court ruled on the obscenity case of Jacobellis v. Ohio in which Justice Potter Stewart wrote that “hard-core pornography” was hard to define, but “I know it when I see it.”

There is a fine line between calling attention to a candidate’s record or calling them to task for their behavior and the political pornography of distortion and fear mongering. Let us be clear, we are challenging ourselves as well as all those who engage in the art and practice of politics to understand when enough is simply enough. Negative imagery, clip art, photo shopped images of Black men apt to invoke fear or that reinforce stereotypical images are not appropriate for campaigns or the media. Period. Their use is NOT a “by any means necessary” proposition.

(Holly J. Mitchell is a California State Senator representing the 26th District. Laphonza Butler is SEIU California president and president of SEIU United Long Term Care.)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 12 Issue 90

Pub: Nov 7, 2014