CALIFORNIA EXPOSE-Marin County is one of California’s most liberal regions and, with its iconic redwoods and stunning coastline, it is also a power center for environmental activism. And so, when a bill to give the state Coastal Commission authority to levy fines against shoreline despoilers came for a vote in the state Assembly in 2013, it was taken for granted that Marin’s new Assemblyman, Marc Levine, would vote for passage. That didn’t happen. Instead, the San Rafael Democrat sat out the single most important vote for his constituents that year – which helped doom the measure.

But Levine was not finished. In Sacramento he would abstain or skip votes on bills helping farm workers and creating a bill of rights for domestic workers. He has also voted against legislation requiring economic impact reports for big box stores and requiring more rate-increase disclosure from Kaiser Permanente. That Levine keeps at arm’s length the progressive values of the 10th Assembly District, which includes much of equally liberal Sonoma County, should come as no surprise. During his two Assembly campaigns he has received hundreds of thousands of dollars from some of the state’s largest business interests.

What is baffling is that Levine, who declined to comment for this article, is neither a DINO (a conservative who is a Democrat in name only) nor a farm belt centrist. He remains a committed suburban liberal. One, that is, who happened to attend a local Mitt Romney rally in 2012 and who felt at ease appearing at a Republican Lincoln Dinner last year. Levine is also no aberration. Rather, he is part of a new breed of Democrat, one exceedingly attentive to big business while tone-deaf toward the Democratic Party’s traditional base, which includes union workers, environmentalists and public school advocates.

At the very moment that California’s Republican Party is melting into electoral irrelevancy, Levine and other hybrid Democrats are appearing in all corners of the state. Their ranks include Bill Dodd, a Napa County Supervisor and former Republican who is running as a Democrat for a wine country Assembly seat, and Palmdale Assemblyman Steve Fox, another erstwhile Republican. Fox, who says he is proud to have earned the California Chamber of Commerce’s highest approval rating for a Democrat, tells Capital & Main that the Democratic Party’s becoming friendlier to business is a positive development.

“We’re pulling the party to the center, towards being more business friendly,” Fox says.

Then there’s Orinda city councilman Steve Glazer, a former top advisor to Governor Jerry Brown, who recently worked as a consultant to the California Chamber of Commerce and its Jobs Political Action Committee. Glazer is currently running for an Alameda County Assembly seat and has fiercely challenged the right of transit workers to strike.

“I am trying to redefine what it means to be a Democrat,” Glazer told Capital & Main. “I think you can be a financial conservative and be a strong Democratic officeholder.”

The rise of what might be called the Corporate Democrat can only be partly explained by shrinking GOP delegations in Sacramento. It is also the product of redistricting and effects of the “top-two primary,” by which members of the same political party can win the top two primary positions and then face off in November. These two structural changes were approved by voters in, respectively, 2008 and 2010. Since then, powerful corporations, agricultural associations and other political high rollers have been turning away from their traditional Republican partners and placing more and more of their chips on the Democratic end of the table – specifically, on candidates like Marc Levine.

These changes are only now catching the attention of Democratic electeds and activists, who see a coming fight for the soul of their party.

“Democrats, we are just as guilty of getting sucked into the influence of money and power about which we criticize Republicans,” state controller candidate Betty Yee told Democrats at the party’s annual state convention last month. Yee, who is a member of the State Board of Equalization, expanded on her wake-up call in an interview.

“What’s different now is the wholesale moderation of Democratic positions on issues we used to own – education, income inequality and poverty,” Yee says.

Illustration by Leighton Woodhouse, Dog Park Media

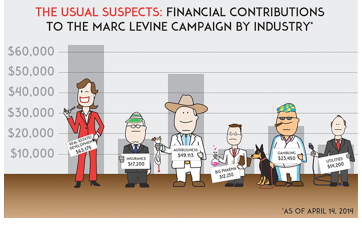

Those issues don’t rate high on the bucket lists of the corporations and millionaires now backing friendly Democratic candidates. Campaign contribution records maintained by California’s Secretary of State reveal a dense constellation of wealthy backers of candidates such as Levine, Glazer, Dodd and Fox. In the 2014 election cycle these benefactors form a Who’s Who of developers, gaming concerns, Big Pharma and agribusiness – and their largesse often overlaps across political races.

Both Levine and Glazer, for example, have received top dollar from Los Angeles billionaire Eli Broad, PG&E, Time Warner, Walmart, Safeway and such pharmaceutical titans as Eli Lilly and Pfizer.

Levine, Glazer and Dodd count as patrons Walmart heiress Carrie Walton Penner, San Francisco magnate Joseph O. Tobin II, the California Chamber of Commerce, public pension reform advocate David Crane, Gap stores scion William S. Fisher and Basic American Foods heir George Hume.

Meanwhile, former Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan has contributed to both Levine and Dodd’s campaigns, while PricewaterhouseCoopers, the California Real Estate PAC and the California Forestry Association PAC are among those donating to both Levine and Fox. And Levine, Glazer and Fox all receive funds from AT&T’s political action committee.

This donor list represents only a selection of contributors who have donated money through mid-April of this year – the number of donors and the amount of campaign spending will only increase as the June primary nears, and then afterwards, leading up to the November runoffs.

“What business is doing is coming to terms with the new structure of politics in California,” says Raphael Sonenshein, executive director of the Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute for Public Affairs at California State University, Los Angeles. “The top-two primary [system] really opens the door to be able to support business-friendly Democrats.”

Fernando Guerra, a political science professor and director of the Thomas and Dorothy Leavey Center for the Study of Los Angeles at Loyola Marymount University, agrees.

“This new environment,” says Guerra, “where Democrats are very dominant, and with new electoral laws, allows for a strategy for electing moderate Democrats in districts particularly defined as liberal-leaning districts.”

Indeed, a recent University of Southern California study found that the electoral reforms in California are associated with an ideological shift toward the center for Democrats (i.e., in a rightward direction) in California’s state legislature — with no perceptible move to the center from the Republican Party. Except, perhaps, from Republicans who have simply switched parties. The legislative effects of such defections have yet to be gauged.

“It’s something that may look as though I switched my party so I could run for this seat,” admits Bill Dodd, the former Republican who is running for the Fourth Assembly District seat. “Nothing could be further from the truth. I fit comfortably under the Democratic tent.” Still, when asked whether he has a better chance of winning the Assembly seat by running as a Democrat, Dodd doesn’t hesitate with his answer.

“Clearly,” he acknowledges. “If you look at the registration in the district and the history of the races, this district is a predominantly Democratic leaning district.” Dodd is sitting on a campaign war chest of nearly $528,000, which eclipses even Levine’s huge treasury. Dodd’s contributions come mainly from wineries and other businesses — as they have since his first supervisorial election in 2000.

Then Dodd was a political novice and “the Chamber of Commerce candidate,” as James Conaway described him in The Far Side of Eden, Conaway’s book about development in the Napa Valley. Yet Dodd also boasts deep funding from individuals who, like David Crane, are influential advocates of cutting public employee pensions or, like Greg and Carrie Penner, are wealthy supporters of school privatization – views that run counter to longstanding Democratic Party positions.

In 2012 the California Chamber of Commerce and other business groups played a key role in targeting a pair of progressive, pro-labor Democratic incumbents in two liberal districts. In Northern California, Marc Levine narrowly defeated Michael Allen, while in the 50th Assembly District, which includes Santa Monica, challenger Richard Bloom squeaked by Betsy Butler. Levine and Bloom (who was then mayor of Santa Monica) were widely considered friendlier to business than Allen and Butler.

“Those are two shining examples of candidates that might not have been elected pre-top two primary,” says Franklin Gilliam Jr., dean of the University of California, Los Angeles’ Luskin School of Public Affairs. The USC study similarly pointed to these races, adding that “Levine supported the CalChamber in 43 percent of votes, which is high for a Democratic legislator.”

In fact, the Chamber’s Jobs PAC had paid at least $100,000 for polling and mailers that were used to attack Allen and Butler. A group affiliated with the Western Growers Association was heavily involved with the attack mailers – which played a role electing Levine and Bloom.

It’s not unusual for big business to hedge its bets by contributing to liberal candidates. Likewise, the mere acceptance of corporate money doesn’t guarantee a candidate will always vote business’ way.

What raises eyebrows about Corporate Democrats, however, is the preponderance of corporate money in their coffers, which more resemble the treasuries of traditional Republican candidates than of progressives. At first glance, Corporate Democrats may not seem to be conservative surrogates, thanks to their votes for causes dear to progressives and because of the ratings they receive from liberal activist groups.

To look at the high rankings (often in the 90 to 100 percentiles) bestowed by environmental organizations, reproductive-rights groups and unions – and correspondingly low scores from, say, conservative tax organizations and gun lobbyists – Corporate Democrats have little trouble appearing to be pragmatists who are forced by circumstances to stand up to their party’s base for the common good of California.

Yet the fact remains that California is the most progressive state in the nation, governed by the most progressive wing of a Democratic Party that has discovered its Sacramento supermajority is not so super. (What’s stopping the state from enacting more visionary legislation than it has since 2012? Or from offering its low-income workforce a higher minimum wage than $10 an hour – and sooner than 2016?) Unlike Washington D.C., where progressive reforms have been thwarted by a determined conservative opposition, in California that opposition comes from within. And, voting records show, this opposition does not necessarily exercise power in obvious ways.

Once elected, Corporate Democrats don’t always flex their muscle by openly sponsoring or supporting business-friendly bills, but sometimes by doing nothing – by abstaining from voting on bills that business opposes. A single abstention can mean life or death for a measure that requires a supermajority to pass.

The bill to give enforcement power to the Coastal Commission, AB 976, for instance, died after Levine and several other Democrats abstained on the final vote. The same thing happened to AB 880, the “Walmart Loophole” bill, which received 46 Aye votes, with 27 lawmakers voting against it and six abstaining. A total of 54 Ayes, or a two-thirds supermajority, was required.

Although Levine voted Yes, three other Democrats voted against the bill, while five more abstained.

The California Chamber candidly acknowledges the importance of persuading Democrats to abstain from voting as part of its strategy to defeat bills business opposes. In its website recap of legislators’ 2013 voting records, the Chamber notes, in a section titled “When Not Voting Helps”:

Sometimes a legislator is unwilling to vote against a colleague, but is willing to support the CalChamber’s opposition to a bill. In such cases, a legislator may abstain from voting, which will hinder passage of a bill, just as a “no” vote does.

Kenneth Burt, who has taught as a visiting scholar at the University of California at Berkeley’s Institute of Governmental Studies, agrees that the Chamber has been increasingly involved in trying to elect Democrats who are aligned with big business interests. Burt adds that this process has accelerated since the 2010 passage of another ballot initiative, Proposition 25, which allows a simple majority vote to pass the state budget. (Disclosure: Burt also serves as the political director for the California Federation of Teachers, a financial supporter of Capital & Main.)

“Prop. 25 eliminated the ability of a few Republicans to demand additional tax breaks for big business as the price of passing a budget,” Burt says. “As a result, the Chamber could no longer get its Republican allies to hold hostage the whole legislative process.”

Loyola Marymount’s Guerra foresees consequences for progressive initiatives in California that are more profound than the loss of one party’s supermajority.

“I could see,” Guerra says, “in the future almost three parties in California — Republicans, the liberal progressive wing of the Democratic Party and moderate Democrats.”

Such a tectonic divide may already be in motion.

(An investigative reporter for more than three decades, Gary Cohn won the Pulitzer Prize for Investigative Reporting in 1998 for his series The Shipbreakers, detailing the dangers to workers and the environment when old ships are dismantled. This column was posted first at CapitalandMain.com. Read more articles by Gary Cohn. Illustration by Lalo Alcaraz

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 12 Issue 32

Pub: Apr 18, 2014