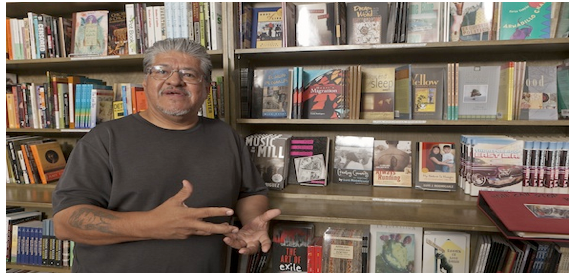

WHO WE ARE-There is little that Luis J. Rodriguez has not done in his life. The 60-year-old Chicano poet and best-selling author has been a member of a gang, faced felony charges, struggled with drug addiction, worked in various countries as a journalist, painted murals, taught prisoners, organized against war and racism, and run a cultural center and bookstore in Los Angeles.

Now he wants to be governor of California.

Rodriguez gained national fame with his 1993 memoir, “Always Running, La Vida Loca: Gang Days in LA,” about his teenage years in a gang struggling with routine violence and the challenges of being an immigrant. Writing in the first chapter, Rodriguez evoked the day-to-day reality facing young people in his community: “But on those days the perils came out too—you could see it in the faces of the street warriors, in the play of children, too innocent to know what lurked about, but often the first to fall during a gang war or family scuffle.”

His lyrical prose and brutal honesty earned him numerous accolades, including a Carl Sandburg Literary Award. But it also brought on a number of campaigns to ban the book from various schools. “Always Running” earned a spot on the American Library Association’s top 100 banned books list and Rodriguez says it is one of the most checked out and most stolen books from public libraries.

With more than 400,000 copies sold, “Always Running” launched Rodriguez’s illustrious writing career. He now has more than a dozen nonfiction and poetry books under his belt and has won more awards, including the PEN Josephine Miles Literary Award and the Paterson Poetry Book Prize.

Today, he runs the beloved Tia Chucha’s Centro Cultural & Bookstore in the Sylmar area of Los Angeles, a crucial space for low-income communities of color to explore literature, politics, music and art.

In a recent interview, I asked Rodriguez why he is running for governor of the nation’s most populous state and the 10th largest economy in the world, and why he is in a race against the popular Democratic incumbent Jerry Brown. His answer was simple: “I’m trying to tap into the discontent of people who feel that the Democrats or Republicans don’t represent them ... and who feel that the electoral process is not really speaking for them.”

More than 20 percent of California’s voters classify themselves as “decline to state,” meaning they do not want to be affiliated with either the Democratic or Republican party. Rodriguez hopes to persuade those voters to side with him and thereby challenge Brown to tackle big issues such as poverty, prison reform, health care and climate change.

Just as President Obama’s tenure has dampened progressive criticism on a national level concerning matters such as wars, corporate misdeeds and climate polluters, Brown has provoked a similar effect in California. Brown is a solid Democrat in that he has taken up some progressive causes in the state such as solar energy and funding public education. But, like many establishment Democrats, he has also been wary of taxing corporations, championed the environmentally destructive practice of fracking and refused to significantly reform the state’s broken prison system, among other actions.

So, just as a vocal independent can draw attention to important issues ignored by the two major parties in a federal election, a candidate like Rodriguez has the potential to push an already progressive state electorate further to the left.

Fittingly, Rodriguez has won the endorsement of the California Green Party even though he is running as an independent candidate. The Green Party’s values of sustainable and equitable democracy are clearly reflected in his ambitious platform, which takes aim first and foremost at California’s high poverty rate. Rodriguez told me, “I’m talking about ending poverty. Why not?”

Despite its enormous wealth, California has the highest poverty rate in the country, approaching 24 percent, the U.S. Census Bureau has found after adjusting for the state’s high cost of living. “Almost everything stems from [the fact that] people cannot survive,” Rodriguez summed up. “We have to fight for a state that keeps people here and keeps people thriving.”

To that end, he poses a challenge to the current economic system itself, saying, “Capitalism cannot feed everybody, cannot house everybody.” So, he asked, “how can we have a world that is equitable, where everybody is thriving?”

His answer is to go beyond what Brown, and even what Democrats and President Obama consistently rely on nationally, and that is raising the minimum wage. Although Brown signed a bill last year increasing California’s minimum wage by 25 percent, to $10 an hour by the year 2016, he has opposed a severance tax for oil companies operating in California.

Rodriguez believes such a tax, which even states like Alaska and Texas impose, should be enacted to help pay for anti-poverty programs. In other words, he wants government to “work for everyone,” rather than just corporate and wealthy interests.

In addition to taking on poverty, Rodriguez wants to “end the California prison system as we know it.”

There have been few, if any, gubernatorial candidates in California who can claim the level of personal experience with the state’s brutal prison system as Rodriguez. The former gang member was candid about his tumultuous past, telling me matter of factly, “I was arrested since I was 13 years old for various things. I was actually on ‘Murderers Row’ when I was 16. I was arrested for attempted murder when I was 17. I was facing a lot of prison time when I was 18.”

In a classic story of redemption, reminiscent of the trajectory of Malcolm X’s life, Rodriguez was saved by a larger cause: social justice and politics. He explained, “To pull myself out I needed something bigger. ... Because the Chicano movement, the movement for civil rights, really spoke to me, I found meaning and got away from the gangs.” When he finally got out of prison and left gangs, he was convinced he “never wanted to be a criminal again.” Instead he focused his energy on the Chicano movement of the 1960s, actively organizing and participating in demonstrations such as the Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War in 1970.

Today Rodriguez is back in the prison system, this time conducting writing workshops for inmates. He knows intimately how broken the system is. California prisons are bursting at the seams with more than 100,000 people being incarcerated in facilities meant to house half that number. Even the federal government and U.S. Supreme Court have ordered the state to remedy the situation.

Nowhere is the racism of the justice system more apparent than in California: 75 percent of the prison population consists of Latinos and African-Americans. And conditions on the inside are so harsh that inmates have carried out historic hunger strikes for the most basic of rights.

Rather than cooperate with the federal edicts addressing some of these issues, Brown has often challenged them. For example, he repeatedly put off a Supreme Court-mandated reduction of the state’s brutally overcrowded prisons.

Rodriguez believes that, like past governors, Brown is beholden to the politically powerful prison guards union, and that “this is why we have the worst, the most expensive and the most overcrowded prison system in the whole country.”

Rodriguez sees poverty as intimately linked with incarceration, calling California’s prisons “the largest state-sponsored poor people’s housing.” According to him, the majority of prisoners in California are there because they were “simply trying to survive” by stealing or selling drugs. Eliminating poverty would reduce the prison population in the long term, he said. And in the meantime, as governor he would embrace restorative justice practices, drug treatment and mental health programs as the cornerstones of his prison policy.

On the issue of health care, Rodriguez rejects the Affordable Care Act, calling it “an insurance industry boondoggle.” He should know—being a freelance writer he ranks among the nation’s 47 million uninsured and is now attempting to comply with the new law and buy a plan through California’s online exchange only to find that health insurance is still unaffordable for him. Instead of the ACA, which Brown has enthusiastically embraced, Rodriguez favors a single-payer system.

This is not a pipe dream; in fact, California’s legislature twice passed a bill in 2006 and 2008 that would have launched a “Medicare-for-all” single-payer health care system, but it was vetoed both times by then-Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. Now, despite Democrats controlling a majority of seats in the state legislature, many, including Brown, are reluctant to relaunch a campaign for single payer.

But Rodriguez insists that a single-payer system is the best path, simply because “health is a necessity. Health is not a luxury. You cannot continue living and working and paying bills if you’re not healthy.”

It is not surprising for anyone familiar with Rodriguez’s body of literary work and his leadership at Tia Chucha’s that as a gubernatorial candidate, he also calls for arts, culture and a “creative economy” to be accessible to everyone. All people need art, he said, because “we have not just material poverty but a poverty of imagination, a poverty of dreaming, and of vision.”

As someone who found transformative redemption through poetry and writing, he wants to see arts funding concentrated on poor communities because “there are whole neighborhoods in California where for miles and miles you cannot find an art gallery, a bookstore or a cultural space.”

Rodriguez’s platform hits all of the major points progressive candidates espouse including immigrant rights, high-quality free public education and climate justice (he is an environmentalist who prioritizes a cleaner, greener California and rejects Brown’s embrace of controversial practices like fracking).

But what sets him apart from most progressive candidates is his personal experience with so many of the actual injustices progressives want to fix: poverty, gang violence, racism and the broken criminal justice system. Generally ambitious politicians work hard to bury their skeletons, but Rodriguez sees his colorful life as an asset. “We need people who’ve been through what I’ve been through,” he said.

“My whole struggle to personally change is also endemic to why must we have social change. I think it’s connected. It’s not separate.”

Click here to watch a video of my unedited interview with Luis Rodriguez, discussing his political campaign for governor of California and sharing one of his poems.

(Sonali Kolhatkar is the host and producer of KPFK Pacifica’s popular morning drive time program Uprising, based in Los Angeles. She is also the Co-Director of the Afghan Women’s Mission, a US-based non-profit solidarity organization that funds the social, political, and humanitarian projects of RAWA. This column was posted first at Robert Scheer’s ecellent Truthdig.com)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 12 Issue 21

Pub: Mar 11, 2014