MAILANDER’S LA - It was a watershed moment for gays and lesbians across the nation. President Obama used the occasion of his Second Inaugural Address this past Monday to esteem gay rights and women's rights and civil rights for African Americans, all in one breath.

"We, the people, declare today that the most evident of truths—that all of us are created equal—is the star that guides us still; just as it guided our forebears through Seneca Falls and Selma and Stonewall..." the President told the nation and the world on January 21, shortly after he had taken his second Oath of Office.

Across the decades, "Stonewall" has become shorthand for LGBT rights as "Seneca Falls" has for women's rights and "Selma" for African American civil rights. And all these places in the past few generations have become nearly as much a part of a general American consciousness as Bunker Hill, Gettysburg and Wounded Knee have.

But few here in Los Angeles … even today … are aware of this city's own legacy to gay and lesbian advocacy, which predates even Stonewall. And LA's civic leaders, from Yorty's day right through today, have done an extremely poor job of preserving that legacy.

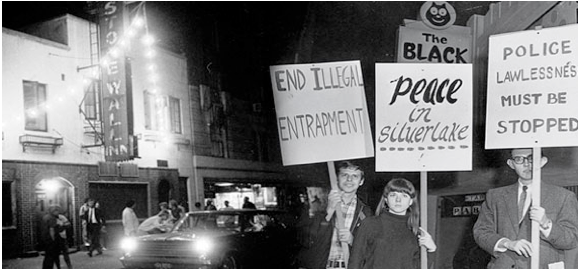

In 1967, two years before Stonewall, a new bar on LA's eastern Hollywood fringe called The Black Cat Tavern was open for business for New Year's. As gay couples kissed to celebrate the New Year, undercover LAPD moved in and arrested thirteen patrons, including two who were later registered as sex offenders for doing so. A few days later, two hundred protesters came to The Black Cat to protest the actions. The national gay standard bearer The Advocate was founded here in LA later in the year, drawing its initial impetus from that raid and protest.

Today … though The Black Cat was declared a Historic site by the city in 2008 … it exists as such only on a register of historic places, without even a plaque to denote what once was there.

Advocacy is only advocacy, not conversion, and change did not come overnight. Inroads towards acceptance were difficult and often even impossible to blaze in LA.

After New York's Stonewall Rebellion, some of LA's top gay leaders formed Christopher Street West, in part to bring to the city a gay pride parade. This was for a while the only such parade in America for which the city officially closed down streets.

Despite its official imprimatur, the LA gay pride parade that Christopher Street West brought to Hollywood continued to experience high tension between participants, LAPD and business community throughout the next decade. The parade felt obliged to leave LA in 1979 for the then-unincorporated area soon to become West Hollywood.

That wasn't the end of the LA's own gay and lesbian community's efforts in Los Angeles to bring to the city a signature event of its own. In 1980, the city granted permits to a group in Silver Lake to stage the first Sunset Junction Street-Fair, an increasingly outré weekend celebration that constantly pushed the envelope both as gay pride event and top line civic festival.

While there has been some revisionist history of the event since 2002, repurposing the festival's original intentions to the celebration of gay and lesbian communities and Latino communities alike, Sunset Junction became a kind of gay mardi gras nearly immediately. Anchored around the same strip of Sunset Boulevard on which The Black Cat Tavern resided, it was always a gay-theme-dominated attraction. Through the eighties and nineties the festival grew in numbers and reputation throughout gay America.

The city killed this one too, very recently, in 2011, in a dispute with promoters, over policing fees. Thus the City of Los Angeles has nearly completely eviscerated what has been the gay zeitgeist of East Hollywood and Silver Lake, whereas Stonewall and Christopher Street have become synonymous with the advancement of gay and lesbian rights.

And just last year, the city refused to move a muscle again as another gay cultural landmark disappeared.

The Other Side, a Hyperion bar with a clandestine entrance, which has been billed (and indeed billed itself) as "the last gay piano bar in Los Angeles," closed its doors for good last June.

Already the subject of a 2006 documentary by Jane Cantillon (who is also chronicling its closure), The Other Side was shuttered to make way for a sports bar.

LA politicians often harp on the need for cultural tourism. As it happens, the extended isosceles triangle formed by Griffith Park Boulevard, Sunset, and Hyperion was, in point of fact, a kind of Gay Rights ground zero. But LA's political class have stood on the side of cowardice while New York and San Francisco have both swooped in to lay grander claims to history--history that belongs to Los Angeles and especially to Silver Lake as much as it belongs to other parts of America.

Nothing should be taken away from the people of New York and San Francisco. Here in LA, many local politicians claim to be great friends to the gay and lesbian community. But as it happens, these same local politicians have done just about everything they could to eviscerate Silver Lake's, Hyperion’s and Sunset Junction's gay political legacy--a story that demands to be told, as much as it may embarrass the city to tell it.

(Joseph Mailander is a writer, an LA observer and a contributor to CityWatch. He is also the author of New World Triptych and The Plasma of Terror. Mailander blogs at www.josephmailander.com.)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 11 Issue 8

Pub: Jan 25, 2013