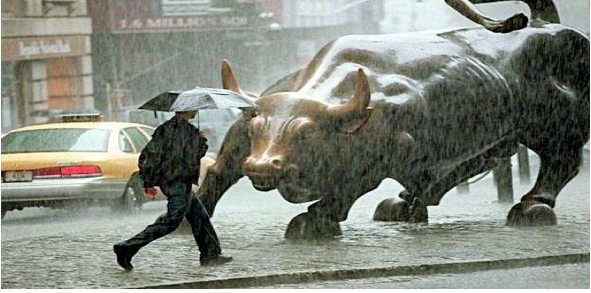

REVELATIONS RECEIVED AND FILED? - This week, New York City experienced a catastrophic infrastructure collapse at the hands of a tangential brush with a Category I hurricane—a hurricane whose winds blew two-thirds as hard as Katrina’s—even as the striping for its bike lanes was barely dry and the lawn chairs in Times Square had been only recently put away.

By thinking like a speculative realtor rather than a tough city boss, billionaire Mayor Michael Bloomberg persistently delayed vital infrastructure improvements to New York City—until it was too late. Other cities, especially Los Angeles, would do well to heed this tragic example.

What has happened to NYC would be tragic enough even if environmental groups had not been vehemently sounding alarms about the possibility of such scenarios all throughout the Bloomberg mayoralty and even in the run-up to Sandy. But they were, and for years. Most recently, a now prophetic jeremiad at the New York Times, “New York is Lagging as Seas and Risks Rise” was published on September 10—just seven weeks ago—and recounted the history of the warnings of various agencies to the City.

“They lack any sense of urgency about this,” Douglas Hurd, an engineer with the Storm Surge Research Group, told Times reporter Mireya Navarro. “You can’t make a climate-proof city,” Adam Freed the City’s former director of its Office of Long Term Planning and Sustainability countered.

New York’s prioritizing of massive speculative real estate projects and their collateral of pocket parks, bike lanes, and lawn chairs above badly needed infrastructure projects over the past decade has brought the kind of catastrophe to the City that other cities controlled by tippity-top financial bogeymen—cities such as Los Angeles, where perennial gamers like Eli Broad and Richard Riordan still have far too much control of politicians and events—would do well to heed.

The obey-the-richest disease has caught on in Los Angeles to such an extent that nearly all the top candidates for Mayor in 2013 remain devoted to erring on the speculative side, still promoting transit hub development, megastructure condo and rental blocks, and renter-appeasing bike lanes, all while leaving potholes and the repair of failing water mains to private companies who win their contracts by pledging to do the job as quickly and as cheaply as possible.

If other great cities across the country thought Katrina’s strike on New Orleans was an anomaly born of poverty, neglect, and political malfeasance, they can now bear New York’s witness to the fact that even the nation’s richest, most progressive, and politically maverick metropolitan area is just as vulnerable to catastrophe as any old Midwestern flood plain.

Mayor Bloomberg, the twentieth richest man in the world, has never been a realtor per se, even if he grew up in a household that anchored his real estate sensibility. But like many realtors, he is in love with the “invisible hand of the marketplace.” He loves big residential projects, and he thinks government is a mere “necessary evil” even as he presides over it.

Like Mayor Villaraigosa and most LA 2013 candidates, Bloomberg has in the past been quick to hop on a bicycle to make a point about transit options. And when catastrophe finally hit, Bloomberg begged commuters not to take cars into Manhattan. But the first kind of public transit to recover was the humble, much maligned, unglamorous, old fashioned bus system.

The irony of so many of Bloomberg’s speculator-friendly touches—the fluff—on which New York City decided to hang its post-9/11 hat were evident everywhere in the aftermath of Sandy. Hipsters, temporarily amused with their own inconvenience, clustered around Starbucks that still boomed wifi, tweeting their front-row calamity observations to far flung friends. Chelsea interns, actors, writers carted power strips far uptown, to recharge their cells at Grand Central and other public points north.

Pedestrians from Jersey were beating the speed of auto bridge traffic into the City, even as one bicycle a minute might utilize the bridges’ bike lanes. All this unfolded as a problem crane that had been cited many times for code violations but never shut down, dangled 1,000 feet above Manhattan, hopeful of putting the final touches on New York's tallest residential project yet.

But the city that could dare to build 1,000 feet into the sky forgot to shore itself up at sea level. The too-short sea walls were never in doubt of failing at some point soon; indeed three of the top ten flooding incidents of New York’s past century have occurred in the past thirty months.

Once the low walls on the south side were breached, Con Ed did not have much of a hope in Lower Manhattan, where much of its power plant—which endured a tremendous transformer explosion in the middle of the storm—resides a scant twenty feet above ordinary high tide level. (Con Ed, for what it’s worth, reports $13 billion in revenues a year and $40 billion in assets—it has the ability to make its transformers secure in a flood).

It is bad enough that Lower Manhattan, which faces the Ocean directly, is not protected by flood gates or any kind of levee system, but the subways and tunnels of Lower Manhattan aren’t shored up with flood control containment caps.

Even backup hospital generators failed in the storm. Three of them failed during or after Sandy—one in New Jersey and two in New York City. Why do backup hospital generators keep failing when they are tested in advance of every approaching storm? Because all three that failed were able to skirt present-day regulations: they were installed in basements before new regulations required them to reside above ground. The hospitals certainly have enough money to get it right; but the City didn’t have the political will to insist that there be no exceptions to new code.

In the 1990’s, it was Los Angeles that was revealed to be the vulnerable city, as earthquake, flood, and civil disturbance readjusted the whole demographics of not only the city but the whole west coast. The catastrophe of Katrina and the government mismanagement that followed similarly scrambled New Orleans, leaving behind a shell of the city it once was.

And in the late zeroes in Los Angeles, the DWP began, after a year of dramatic failures, to repair the decades-old at-risk water mains that suddenly began rupturing all throughout the pueblo.

LA’s DWP has also been obliged to take a couple contaminated reservoirs offline. And who knows how much damage the contamination caused? No epidemiological study has ever been conducted. Even the cause of the mysterious sudden death of the largest lotus bed in North America remains a secret.

Because of the decision to prioritize speculative real estate projects above infrastructure, New York City faces, in many ways, the most difficult challenge of all these cities: the challenge of building and rebuilding costly infrastructure projects that will certainly raise the cost of living in the City much more, even after building ever costlier housing all through the Bloomberg years.

The question for New York now becomes not when the city’s infrastructure will be fixed, but who will be willing to stick around to pay for fixing it. If the past is prologue, we may expect to find a very different New York City in five years, as we have a very different New Orleans now, and as we presently live in a very different Los Angeles than the one we knew before its own robust time of troubles.

(Joseph Mailander is a writer, an LA observer and a contributor to CityWatch. He is also the author of New World Triptych and The Plasma of Terror. Mailander blogs at www.josephmailander.com.)

-cw

CityWatch

Vol 10 Issue 88

Pub: Nov 2, 2012