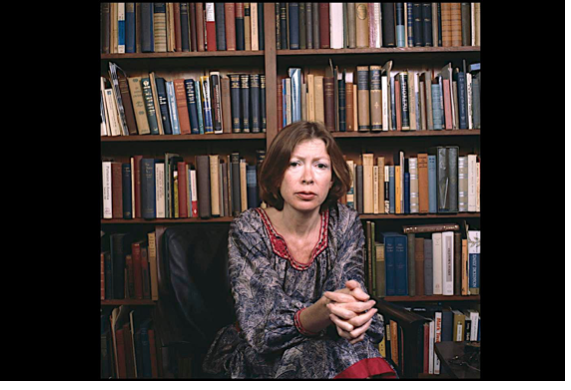

CommentsLAKEWOOD STAKEHOLDERS - When Joan Didion passed away on December 23 of last year at the age of 87, Governor Gavin Newsom praised her as “easily the best living writer in California.”

Numerous articles hailed her insights on California (the Los Angeles Times alone carried 8 articles in the first week). One of her lengthy essays published in The New Yorker in 1993, on the Southern California suburb of Lakewood, was singled out for her understanding of the dark side of California suburbia.

By 1993, Lakewood, a suburb built on the post World War II defense, aerospace and oil boom, was suffering a series of plant closures and cutbacks. Didion wrote about the job losses, and also portrayed an industrial middle class in decline. The workers, buoyed by federal policies promoting home ownership, were, in her words, an “artificial ownership class”, fated to fail. Further, Didion described a largely white suburban population as resistant to change and resistant to the inclusion of other ethnic and racial groups.

The twenty-eight years since Didion’s celebrated essay have shown most of what she wrote in the essay to be wrong. She was wrong about economic decline, wrong about home ownership, and wrong about the social and racial attitudes of Lakewood residents.

Lakewood’s story is worth briefly recounting. Didion’s narrative on Lakewood and blue collar anger and bewilderment has taken hold since 1993, and with her death, this flawed narrative is getting new attention.

Lakewood: Economic Decline and Revival

Lakewood is one of the most colorful stories of California’s post World War II suburban growth, and Didion skillfully tells it. Prior to World War II, the area that became Lakewood consisted of “several thousand acres of beans and sugar beets just inland from the Signal Hill oil field and across the road from the plant that the federal government completed in 1941 for Donald Douglas.”

In 1949, three California developers Mark Taper, Ben Weingart and Louis Boyar started construction of Lakewood, as a master planned city of 17,500 homes. They perfected techniques of mass housing productions, so that the 17,500 homes were built in less than three years. In the spring of 1950, thirty thousand people showed up for the first day that homes were put on the market. As Didion describes the flurry of activity: “Deals were closed on 611 houses the first week. One week saw construction start on 567. A new foundation was excavated every fifteen minutes. Cement trucks were lined for a mile, waiting to move down the new blocks pouring foundations.”

Lakewood thrived during the next three decades on the good paying jobs available at the nearby aerospace and defense plants: McDonnell Douglas, Hughes and Rockwell. Added to these jobs were thousands of jobs at the Long Beach Naval Station and Naval Shipyard, and the subcontractors who did business with these major employers.

By 1993, though, when Didion came to Lakewood, the aerospace and defense industries had suffered a series of setbacks. The Rockwell plant closed in 1992, with a loss of 1000 jobs, and other plant closures in the region over several years came to total 21,000 jobs.

Didion describes an environment of economic fear and bewilderment. One of the parents tells her, “When you take your kid to a birthday party and your wife starts talking about So-and-So’s father just being laid off—there are all kinds of implications…And you realize, yeah, this bad economic situation is very real.” Even workers still employed worry that their role in the economy will soon be eliminated, with no replacement role. And for Didion this is the future: aerospace and defense plants, built on Cold War politics, closing, with workers set adrift.

Yet, while employment in the region’s defense and aerospace plants did decline, it did not end. A number of the aerospace/defense plants have continued to operate today, including Boeing’s Global Design Center, Aerojet Rocketdyne (a division of Lockheed Martin), and Raytheon Technologies. New manufacturing facilities have come into the Lakewood area, including a SpaceX facility, Relativity Space, Rocket Lab USA, and a Virgin Galactic facility.

Also, as with other parts of California, other jobs emerged in the Lakewood region, in even greater numbers. Lakewood is part of the Los Angeles/Long Beach Metropolitan region, as measured by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). In 1990, the region had 4,198,000 jobs. As of the most recent BLS report through November 2021, the region had increased to 4,368,000 jobs. The total number of manufacturing jobs in the region has decreased since 1990, but still stands at a sizeable 309,100 jobs today, part of the more than 1,270,000 manufacturing jobs in the state.

Expanding Home Ownership and “A Stake in the Land”

Didion’s narrative of middle class suburban California is not only one of economic decline, but also one of social dislocation. The worker-homeowners who bought the Lakewood homes were propped up by the federal defense spending and federal subsidies for home ownership. In Didion’s view, they never formed a true middle class. “What had been lost to create and maintain an artificial ownership class?,” she asks at one point. “What happens when that class stops being useful?” Didion answers:

“Lakewood exists because at a given time in a different economy it seemed an efficient idea to provide population density for the mall and a labor pool for the Douglas plant. There are a lot of places like Lakewood in California. They were California mill towns, breeder towns for the boom. When times were good and there was money to spread around, these were the towns that proved Marx wrong, that managed to increase the proletariat and simultaneously, by calling it middle class, to co-opt it.”

It’s not clear what Didion means by “artificial ownership” or “co-opting” the proletariat. The late 1940s and 1950s in California saw a conscious government effort to expand home ownership with the goal of expanding a stable middle class. One of the Lakewood developers, Mark Taper, would tell an interviewer in 1969, “We’ve developed good citizens. Enthusiastic owners of property. Owners of a piece of their country—a stake in the land.” Didion quotes Taper’s statement as indicating the fake boosterism of Southern California developers. But Taper was right. It was the expanded home ownership that underpinned the middle class and the stability it brought to California in the last half of the twentieth century.

Don Waldie grew up in Lakewood in 1950s and 1960s, served for many years as the City’s public information officer, and today continues as part time City archivist. His books Holy Land and Becoming Los Angeles trace the growth of Southern California after World War II, and through his newspaper, online and radio commentary over the years, has been called by some the poet laureate of suburban California.

Waldie authored one of the Los Angeles Times essays on Didion, entitled “What Joan Didion wrote about Lakewood in 1993 wasn’t—and isn’t –the only story to tell”. Waldie reflected on his father and neighbors and how the home ownership that Lakewood, even with its tiny mass produced houses, gave them a stake in the system.

“As far as I could tell by their lives together, my parents did not escape to their suburb” Waldie believes. “Nor did they ever consider escaping from it. They didn't imagine it to be a bunker in which they could avoid the demands of living with other people. My parents and their neighbors understood what they had gained and lost by becoming suburban. More men than just my father have said to me that living in Lakewood gave them a life made whole.”

Didion described Lakewood’s workers as buffeted by historical and economic forces they had no control over. But Waldie emphasizes that his father and neighbors were as much agents of their own history as any other Californians of the time, with no more “dread” or spiritual emptiness as any other Californians.

Today, Waldie still lives in the house he grew up in among new neighbors who are much like the post-war families who bought their homes in the 1950s. A broad base of homeownership, Waldie insists, continues to support Lakewood’s quality of life. Housing data for 2019 show that 72% of the city’s 27,000 homes are owner-occupied. “I continue to live in Lakewood with anticipation,” Waldie says, “because I want to find out what happens next to new homeowners who happen to be my Latino, Black, Filipino, and Asian neighbors.”

Racial Inclusion and Social Capital

In another the Los Angeles Times essays, Times columnist Gustavo Arellano singles out the Lakewood essay as his favorite in the Didion canon, because it unmasks the misogyny and racial animus of Lakewood’s white population. Arellano writes,

“It’s my favorite Didion piece because it captured a moment in time when suburbanites were realizing that Southern California was no longer theirs, and were not happy about it at all.”

It’s a misreading of Lakewood, in 1993 and today. As Waldie notes, the city demographics have changed dramatically in the past 28 years, so much so that the city today reflects the racial distribution of Los Angeles County. Rather than resist change, the existing population during this time welcomed newcomers of all races, including migrants who fled political chaos in Laos, Cambodia and Vietnam.

Lakewood maintains a relatively large cohort of long-time homeowners, who are not embittered or withdrawn but serve as “habitual volunteers”. Hundreds of parent volunteers turn out every year to coach boys and girls sports at city parks; others serve as Neighborhood Watch block captains and Meals on Wheels drivers. The region’s long time service clubs continue—Kiwanis, Rotary, Optimist—and they have been augmented by the newer forms of civic engagement through social media and online neighborhood connections.

***

Though nobody knew it in 1949, when Lakewood was founded, the thirty years after World War II turned out to be a small window of economic dominance in California’s economic history (and America’s economic history). By the 1970s, other countries had rebuilt their economies, global competition emerged in providing goods and services, and this dominance ended.

Didion saw the economic dislocations in California during the 1980s and 1990s, but failed to anticipate the resilience of the state’s economy, and its middle class. A combination of forces have chipped away at the stability and security of the jobs in 1950s and 1960s California. But a different middle class has grown with decent-paying jobs not only in manufacturing but also in transportation, health services, information technology and other major sectors—including occupations not envisioned in the 1960s or even the 1990s.

Many of Lakewood’s original residents were drawn from the Dust Bowl refugees who came to California in the 1930s. A few decades before Didion, another celebrated California writer, John Steinbeck, predicted that these refugees would form a true proletariat that would help move California toward a socialism that Steinbeck favored. Instead, through the property ownership provided by Lakewood and the other post-War suburbs, these refugees and their children came to play an opposite role in California, stabilizing the state politically and economically.

(Michael Bernick served as California Employment Development Department director, and today am Counsel with the international law firm of Duane Morris LLP, a Milken Institute Fellow, and adjunct faculty at Stanford University. His newest book is The Autism Full Employment Act (2021). This story was first published in Forbes.)